In this long read, People’s History Museum’s (PHM) Collections Assistant Jaime Starr recounts the history of HIV activism in the UK, at the time of the HIV/AIDS epidemic through objects in PHM’s unique collection. LGBT+ History Month is celebrated each February in the UK.

While scientists now believe HIV had been present in humans for some years before it was identified, HIV was first brought to public attention in July 1981, after groups of young gay men in the United States were diagnosed with a rare form of cancer. The first cases diagnosed in the UK were identified in winter 1981-1982. At the time little was known about what was causing these men to get sick. The virus HIV (Human Immuno-Deficiency Virus) was not identified until 1986, and there was no effective treatment until 1996. Before this, it was assumed that everyone who became HIV positive would eventually develop AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) and die of the complications. HIV activist Jonathan Blake, who was among the first people to be diagnosed as HIV positive in 1982, remembers,

“They came back and said, “You have a virus, there is absolutely nothing we can give you to help. There will be palliative care when the time comes, and you have about six months to live”, and that was that.”

As most of the early cases were diagnosed in men who have sex with men (MSM), it was first it was described as a ‘gay cancer’ and was even initially given the name ‘GRID’ (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency). Governmental homophobia meant that there was no public health campaign or funding offered to try and prevent infections or find treatments or cures – the Department of Health did not publish advice for UK medical professionals about AIDS until 1985, by which point there had been at least 108 AIDS cases identified – even without an HIV test existing yet, and 46 known deaths in the UK. A government committee on AIDS, to organise policy and public health messaging, wasn’t set up until 1986.

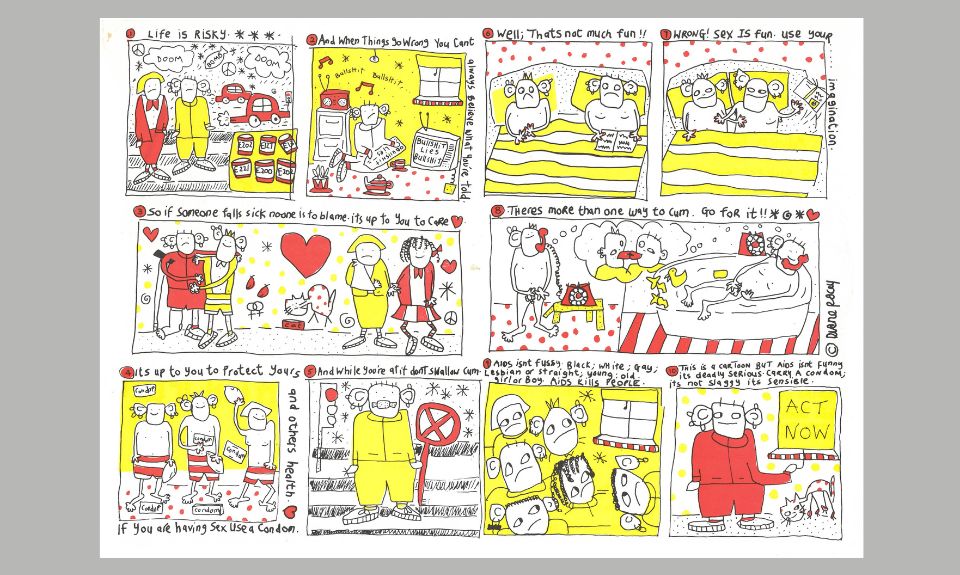

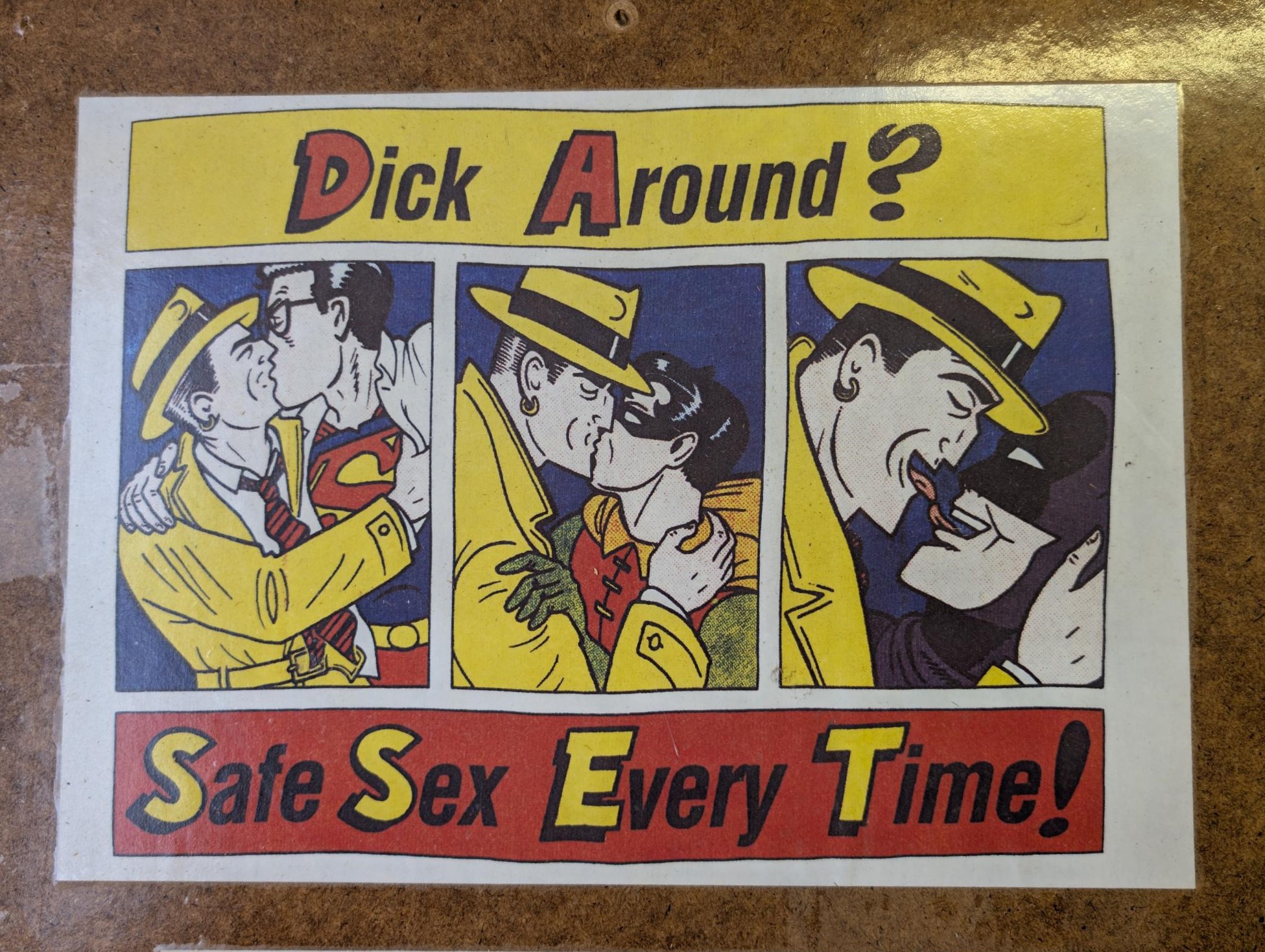

Due to this neglect from the state – as it became understood that sex was a way HIV could pass between people – the sharing of safer sex education came from groups of LGBT+ activists within their communities. Central to this in the UK is the Terrance Higgins Trust (THT), a campaigning and education charity for HIV positive people founded in 1982, which is named after Terry Higgins, one of the first men known to have died of AIDS in the UK. THT, London Lesbian and Gay Switchboard and the Gay Medical Association held public information meetings about AIDS in 1983, four years before the government’s first public awareness campaign.

Community organising focused on harm reduction – encouraging people to have sex in ways which wouldn’t involve sharing bodily fluids, sharing up-to-date health information about medical advances, and fundraising to provide mutual aid for HIV positive people. Mutual aid was important, as the climate of fear meant that being outed as HIV positive, or being presumed to be HIV positive (which some straight people assumed about any gay man) could lead to someone losing their job. Other people perceived as being HIV positive were assaulted in public. The government even passed legislation allowing for HIV positive people to be forcibly quarantined in hospitals under the guise of protecting public health and safety. Forced quarantine was only used once, here in Manchester, where a young HIV positive man was confined in North Manchester General Hospital. HIV activists’ education efforts included trying to reduce stigma and bust myths about how HIV could be transmitted. In Manchester in 1985, six gay HIV activists founded the Manchester AIDSline which later became George House Trust – an organisation which is still vital to HIV activism in Manchester today.

In 1987, amidst growing community anger at the government’s lack of support for HIV positive people, ACT UP London was founded. ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) was originally founded in New York by grassroots activists including Larry Kramer and Vito Russo, and spread around the world, united through the mission of using direct action tactics to end the AIDS epidemic, pressuring governments and pharmaceutical companies to fund treatments and support HIV positive people. Their tactics involved die-ins, protests outside government and pharmaceutical offices, and other attention catching protests. In Manchester, the local branch of ACT UP radically promoted safer sex at Strangeways prison by stuffing tennis balls with condoms to protest the government’s refusal to provide safer sex supplies to incarcerated people, despite rising rates of HIV in prisons at the time.

In 1987, amidst growing community anger at the government’s lack of support for HIV positive people, ACT UP London was founded. ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) was originally founded in New York by grassroots activists including Larry Kramer and Vito Russo, and spread around the world, united through the mission of using direct action tactics to end the AIDS epidemic, pressuring governments and pharmaceutical companies to fund treatments and support HIV positive people. Their tactics involved die-ins, protests outside government and pharmaceutical offices, and other attention catching protests. In Manchester, the local branch of ACT UP radically promoted safer sex at Strangeways prison by stuffing tennis balls with condoms to protest the government’s refusal to provide safer sex supplies to incarcerated people, despite rising rates of HIV in prisons at the time.

In the early days of the epidemic, HIV positive people in hospitals experienced neglect as some healthcare workers refused to clean rooms or bring food into their rooms. This resulted in dedicated HIV wards being opened in hospitals like the Middlesex in London, which was opened by Princess Diana in 1987, and organisations like London Lighthouse being founded in 1988 – this space was a support centre which held drop ins for HIV positive people, and had a hospice ward where people could be cared for with dignity they feared they would not receive in hospital.

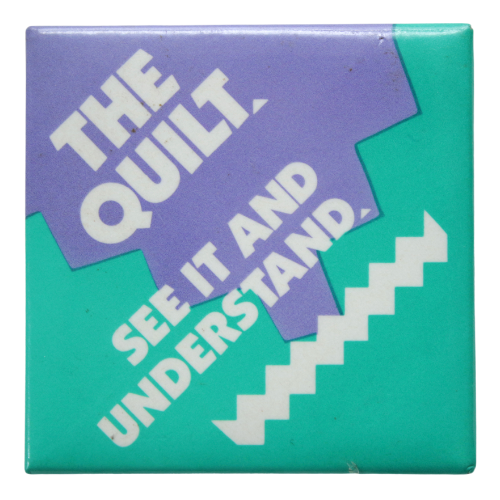

Commemorating those who had died became more prominent as the 1980s went on. 1 December 1988 marked the first World AIDS Day. In the UK, 1000 balloons were released by THT to symbolise the number of known AIDS cases that year. Since the early 2000s, George House Trust has run a candlelit HIV vigil at the end of Manchester Pride weekend. Commemorative art is also important to keeping alive the memories of HIV positive people who are no longer with us. LGSM (Lesbians and Gays Support the Minders) activist Mark Ashton is remembered by his friends Jimmy Sommerville and Richard Coles of the band The Communards in their song ‘For a Friend’. The Names Project AIDS Memorial Quilt, a project begun by Cleve Jones, an American HIV activist in 1987, is now the world’s largest piece of community folk art – each around 1m wide by 2m high panel (roughly the size of an average grave) commemorates a HIV positive person and is usually made by family or friends. The UK Quilt is 150m long, representing 384 people. The US Quilt is a staggering almost 400,000m long.

In 1996, the first effective HIV treatment was introduced, reducing the mortality rate for HIV positive people and improving their quality of life. As life expectancy improved, HIV activists continued to focus on access to treatment, encouraging people to get HIV tested, facilitating support funds and providing care for HIV positive people, and continuing to provide education around safer sex and harm reduction for drug users.

George House Trust, ACT UP, Outrage and other activist groups campaigned to repeal Section 28, a law passed in 1988 which stopped local authorities from ‘promoting homosexuality’, which also prevented LGBT+ safer sex information from being shared with young people. Local HIV campaigner and playwright Nathaniel Hall was diagnosed with HIV in 2003 aged 16; at the time he had no access to inclusive safer sex information. He recalls,

“I was diagnosed with HIV in 2003 when I was just 16.

A young gay boy growing up under the shadow of Section 28 (repealed that very same year), throughout my childhood I absorbed the narrative that being gay meant you were broken in some way, that you deserved ridicule and abuse.

And that gay men deserved it when they got HIV.”

As medication has improved, HIV has gone from a certainty of death to a condition which most people can treat with one pill a day, the life expectancy of HIV positive people has begun to match those of non-HIV positive people. Jonathan Blake, diagnosed in 1982 and given six months to live, has now been HIV positive for over 40 years, and this is becoming the norm, rather than the rarity it was when he was first diagnosed.

In the UK, access to effective medication for prevention and treatment is still a central issue for HIV campaigners too. In the early 2010s a new drug, PrEP (Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis), became available – people who take it can reduce their risk of becoming HIV positive while having unprotected sex. Despite its effectiveness, HIV activists had to campaign for several years for this to be made available on the NHS.

In 2016, medical evidence emerged that HIV treatment had become so effective that HIV positive people taking anti-retrovirals could safely have sex without a condom. The U=U (Undetectable = Untransmissible) campaign encourages HIV positive people to access treatment in order to reach this ‘undetectable’ threshold. It is hoped that this will reduce HIV transmissions in the UK; in line with the UN goal of eliminating new HIV transmissions by 2030.

However, campaigners are aware that HIV rates in the global south, particularly among African women, are not reducing in the same way, due to health inequalities. This has led to UK HIV organisations like ACT UP campaigning on global health equality as an HIV issue, arguing that making testing, prevention and treatment accessible to everyone worldwide, regardless of ability to pay is the only way to stop HIV transmissions. The fight towards this goal continues.

Read about HIV/AIDS activism in a blog about the Mark Ashton Trust.

Get tested with LGBT Foundation

Shop PHM’s LGBTQIA+ Pride collection of items inspired by stories of LGBTQIA+ people and their battle for equality.