A fascinating insight into the Greenham Common Peace Camp with PHM Collections Assistant Morgan Beale.

On 5 September 1981 a march led by a small group of women arrived to RAF Greenham Common in protest of a decision to place US nuclear missiles at the base. Thousands of people would come to join them at what would become known as the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, with the last of the protesters leaving the base on 5 September 2000 – 19 years after they’d first arrived.

In this blog PHM Collections Assistant Morgan Beale takes us through the years in between to share a fascinating insight into this groundbreaking chapter in the history of peace activism. You can book tickets to join Morgan on Saturday 20 September to explore PHM’s peace displays and to view newly catalogued artefacts from the museum store.

Greenham Common Peace Camp was a long-term encampment at the Royal Air Force base Greenham Common in Berkshire. The protesters occupied the military base for almost two decades and became an internationally celebrated symbol of the nuclear disarmament and feminist movements. It is most often referred to as ‘Women’s Peace Camp’, as it was women-led and because the vast majority of protesters were women, although some men and other people were involved.

In the late 1970s, NATO (North Atlantic Treaty Organization) was expanding its nuclear arsenal as the Cold War escalated. This was a period of intense political tension between the Soviet Union and the United States and its allies leading to the deployment of nuclear missiles to military bases across Europe. In 1980, the Conservative UK government announced that they had agreed to house cruise missiles owned by the US Air Force. This deal was struck without any public debate and did not include a ‘dual-key’ system, meaning the US military had ultimate control of nuclear weapons on British soil.

It was due to this growing unease about nuclear weapons being based in Britain and Europe that four friends in Wales came together to respond: Ann Pettitt, Karmen Cutler, Lynne Whittemore and Liney Seward. They chose the name Women for Life on Earth for their group and coordinated a protest march from Cardiff to, the then little-known, Greenham Common, which had been earmarked to house the majority of the US missiles.

On 27 August 1981, a group of around forty women, with a few men and children, began the 120 mile march from Cardiff to RAF Greenham Common. They carried banners and placards and held meetings at local peace groups along the route. Around sixty people arrived ten days later, on 5 September 1981. Their first action was to deliver an open letter to the base commander, saying: ‘We have undertaken this action because we believe that the nuclear arms race constitutes the greatest threat ever faced by the human race and our living planet.’

The founders could never have imagined the number of people who would join the camp. The protesters quickly grew to the hundreds with some setting up permanent camps, which would go on to last for almost two decades. Over the years, several mass protests saw as many as 50,000 people travel to Greenham at any one time to demonstrate.

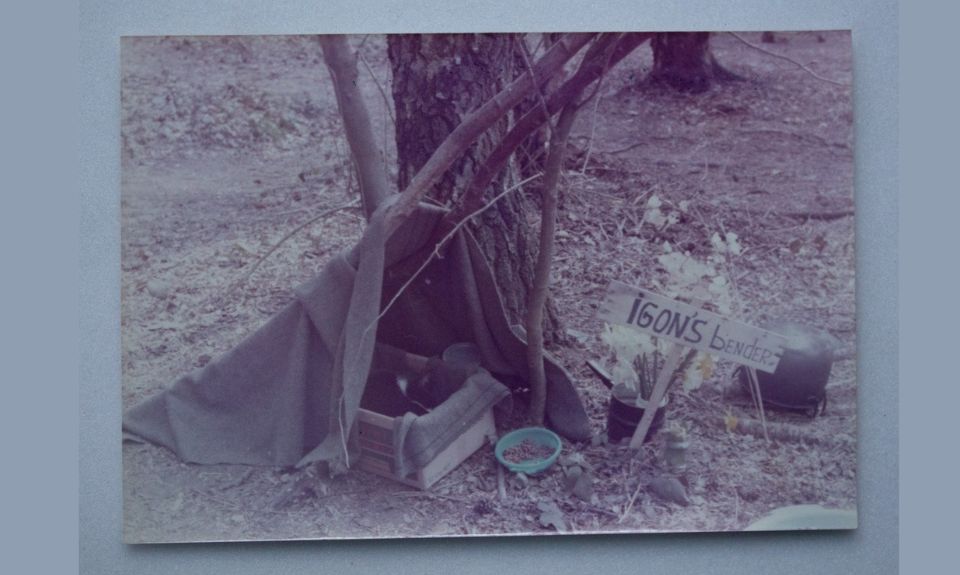

Greenham Common differentiated itself from other peace camps as a women-led protest. From 1982, men were only allowed to visit the camp during the day, and not to stay overnight. The founders, and many who joined them, thought it important to their message to draw a contrast between “the men who make military decisions” and the women protesting, Ann Pettitt later said in an interview. Many were mothers and grandmothers, who brought their children with them to the camp. Split into numerous colour-coded ‘gates’, Green Gate became known as the most child-friendly, establishing a communal creche and school, and caring for the resident cats.

The other gates each grew their own reputation, whether for younger women, the politically radical – who would talk to the press, or even for meat-eaters – who were in the minority at the camp. Many protesters noted how Greenham allowed them the freedom to live away from patriarchal expectations, especially for women from the LGBTQIA+ community. At a time of prevalent homophobia, that included some LGBTQIA+ mothers losing custody of their children on the basis of their sexuality, the camp provided an alternative way of life and respite from daily discrimination. While the camp was known as a women-only space, some protesters later came out as trans men and non-binary people. Charlie Kiss joined as a 17 year old, studying for his A-Levels from the camp. His arrest and imprisonment for protesting at Greenham were formative experiences, and he would later become the first trans man to run for parliamentary election in the UK, standing for the Green Party in 2015.

Although forward-thinking as a feminist space for the time, the camp lacked racial diversity and Black women in particular faced discrimination from the police and other protesters. Amanda Hassan, a Black activist in the peace and Guyanese political movements, was violently arrested by police while living at Greenham. Following arrests, Black women routinely received longer sentences than others for the same offence. Writing about the experience in feminist magazine Spare Rib, Hassan described how her white campmates often refused to see that she was treated differently because of racism. She would continue to call for activists to confront racism within the movement, and from 1983 became the coordinator of the Black and Asian Working Group of Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND).

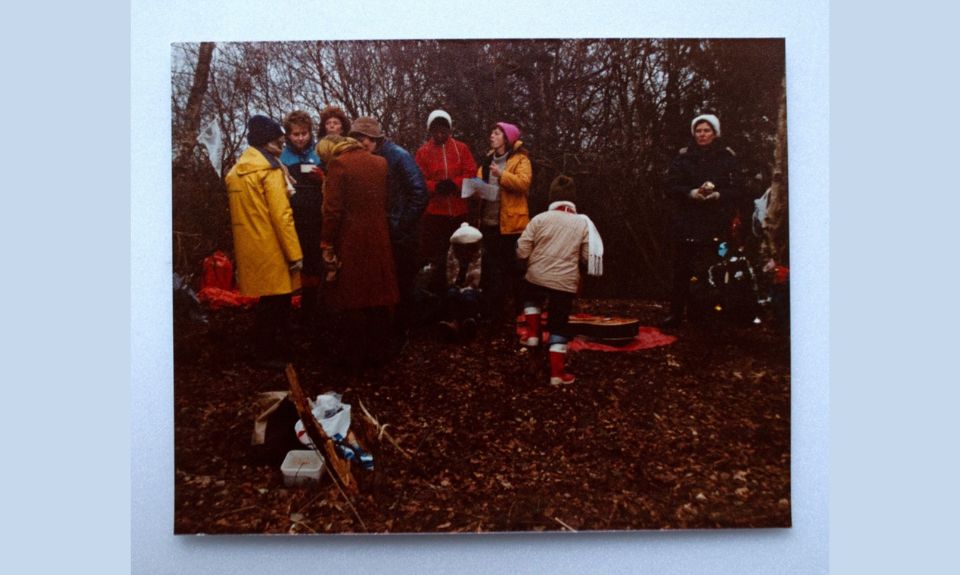

The women maintained uninterrupted occupation of Greenham Common Peace Camp for 19 years, returning after each eviction by the police and local council. Camping in the woods around the base, the protesters regularly decorated the border fence, with children’s drawings, photographs, balloons, banners, and even one woman’s wedding dress. Sit-down protests along the roads into the base were common, with people singing songs and dancing.

Perhaps the most famous one-day demonstrations were Embrace the Base and Reflect the Base. On 12 December 1982, around 35,000 people linked arms around the 9.7km perimeter fence in a powerful display of solidarity. The following year, even more people arrived from around the country when 50,000 people participated in Reflect the Base. In this demonstration, protesters held up mirrors for the military to metaphorically and literally ‘take a long look at themselves’. These individual demonstrations renewed media attention, especially with the sheer number of people arriving at a small base in rural England.

To counteract the disinterest and negative spin by media, the women organised poster exhibitions to share their own voices from inside the camp. These helped to educate others in the peace movement and Greenham-specific support groups sprung up nationwide. For weekend and one-day demos, supporters coordinated coaches and marches to the camp. In 1983, for example, women walked from Cardiff, Merseyside, Bath, Barrow, the Isle of Wight and more in what became known as a ‘star march’ – all converging on Greenham Common. The support groups were therefore an integral part of the camp’s longevity and notoriety, raising funds and awareness in different towns and cities year-round.

In contrast, the right-wing media led a campaign to slander the women, creating a narrative of hysterical, irresponsible mothers who should be at home looking after their children and husbands. At the same time, anti-LGBTQIA+ attitudes were prevalent. One 1983 Daily Mail article attempted to smear the women by calling them ‘militant-lesbian-vegetarian-feminists’. All this combined to move the conversation away from nuclear weapons, despite polls showing a majority of the public actually opposed them.

The government and police were incredibly hostile to the protesters. Defence Minister Michael Heseltine even refused to guarantee their safety from military force in November 1983, just weeks before the arrival of the first cruise missiles to the base. Police treatment of the women escalated with hundreds violently arrested, for offences including singing. In 1989, 22 year old Helen Wyn Thomas was killed by a police vehicle just outside the base. The police ruled her death a tragic accident, though witnesses and Helen’s parents have spent years questioning the decision given the lack of scrutiny of the driver. Even in mourning, certain newspapers called the women angry and sensitive.

The camp’s original aim, for cruise missiles to be removed from the site, was achieved in March 1991, four years after the US and Soviet Union signed a nuclear weapons treaty. However, the camp remained in place until 2000, because the women continued to protest against nuclear weapons. For many who protested at Greenham Common Peace Camp, it was the decision to stay for so long that led to the success of the movement. Thousands of people became politically active and undoubtedly raised the consciousness of the public about the need for nuclear disarmament.

The base’s fences were taken down on 5 September 2000, 19 years to the day since the founding group had arrived. The site of the camp is now public land, with a memorial garden to Helen Wyn Thomas.

Book a place on our Collections Spotlight tour which is taking place to mark International Peace Day. Join Morgan to explore PHM’s peace displays and to view newly catalogued artefacts from the museum store.

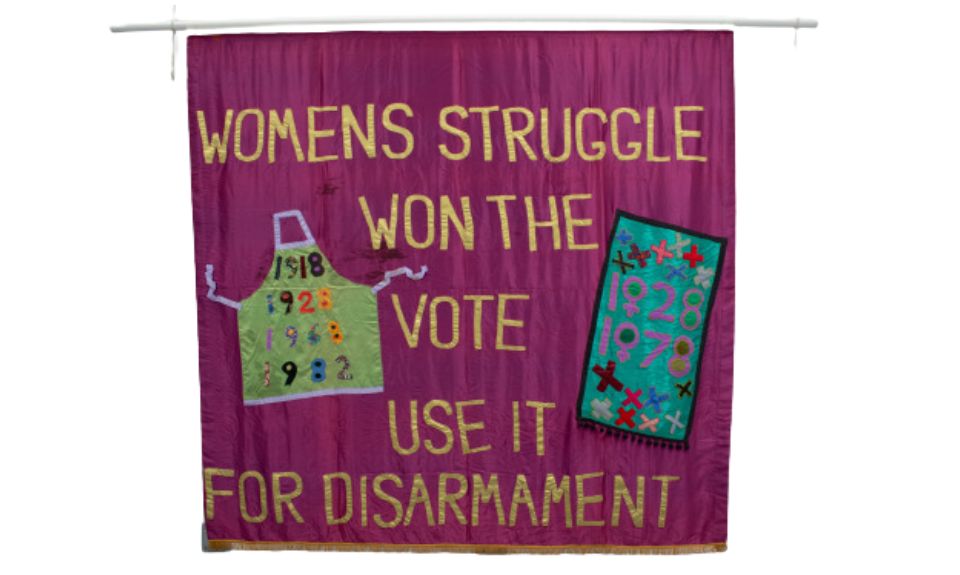

Visit the 2025 Banner Exhibition, which includes the Wokingham Peace Group banner that was made in 1980 by Kay Browning and used at Greenham Common.

Read about symbols of Greenham in another blog by PHM Collections Assistant Morgan Beale which looks into the museum’s recently digitised LGBTQIA+ badge collection.