2024 marks the 40th anniversary of Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM), which formed in the early months of the Miners’ Strike (1984-1985). Joining us to explore this historical moment and the legacy that it created is People’s History Museum’s (PHM) Collection Assistant Jaime Starr.

In the second of two blogs about LGSM, Jaime will discuss the relationship between marginalised communities and striking coal miners. Jaime tackles concerns such as reciprocal solidarity, prejudice in mining communities and the experiences of Black and Asian miners during the strike.

All Out: Dancing in Dulais is a documentary film released in 1985 by Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM). In the film, an off-screen reporter asks LGSM organiser Mark Ashton how he responds to community criticism that the LGBTQ+ community shouldn’t support the miners because “the miners don’t support us”. This question, in various forms, dogged all the solidarity campaigns organised by LGBTQ+ and Black and Asian campaigners during the 1984-85 Miners’ Strike.

“I think all lesbians and gay men who are attacked by the police, attacked by the state, attacked by the media know what it it’s like to be attacked. That’s why we’re here openly as lesbians and gays and as socialists to support the miners. A victory for the miners is a victory for us all.” – Nigel Young, LGSM.

Attitudes to the miners from within marginalised communities were impacted both by personal experiences of prejudice in mining communities – for instance people who had left for other areas due to homophobia and/or racism – and by press presentation of miners as a homogenous white, straight group who did not express solidarity with others.

“The young [Asian] lad that I had woken up [to attend a picket] turned to me and said, ‘this is bloody good isn’t it? You wake me up at six in the morning, only to get this racism from the ones we came to support’. I said, ‘look bro, we can see the bars… but some of them can’t’.” – Mukhtar Dar, Sheffield Asian Youth Movement (AYM).

“We did get people coming up to us who said, ‘I’m from Barnsley, I hate these bastards, that’s why I live in London.’ Other people said, ‘I’m from a mining community, here’s some money.’ It cut both ways.” – Ray Godspeed, LGSM.

In some ways, this perception of a lack of reciprocal solidarity was true – Black and Asian communities were acutely aware that there were ‘closed pits’ in some areas, where migrants, particularly People of Colour could not get work, and this racist hiring practice made community members less willing to support all miners. In her oral history work with Black coal miners, historian Norma Gregory documents that there were also pits like Geddling in Nottingham, which was known as an “international pit” where People of Colour made up an estimated 30-50% of its workforce at the time of the strike. However, even here there was an unspoken understanding among some Black and Asian miners, like John Rogers, that the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) did not support their grievances equally.

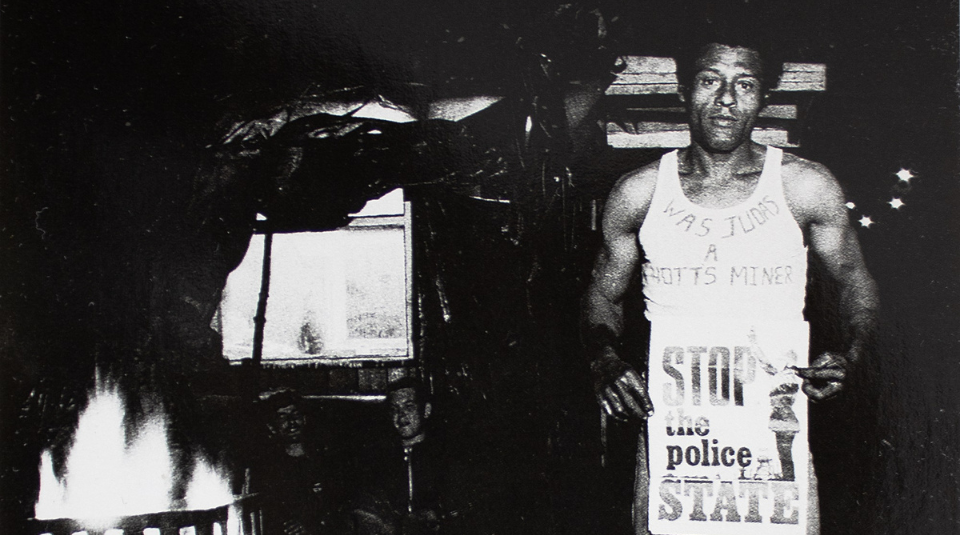

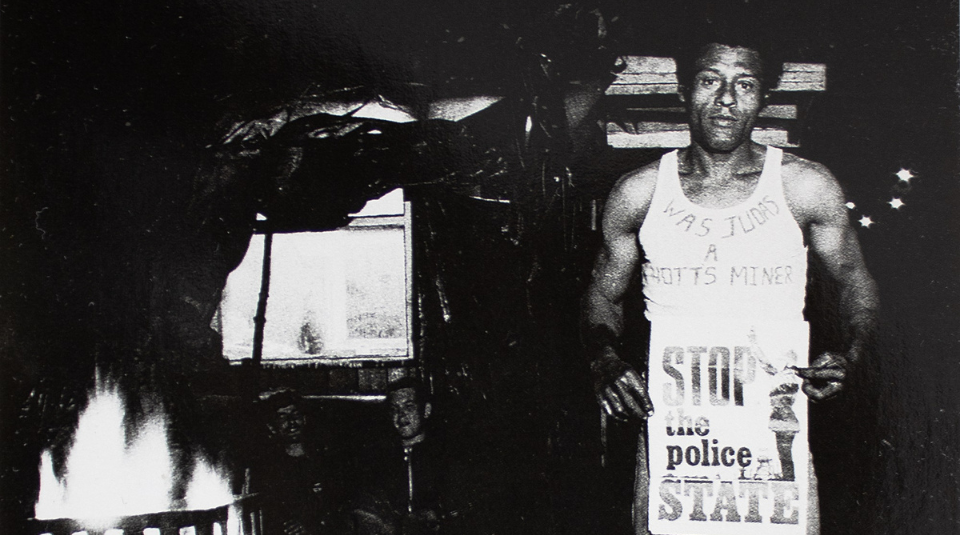

Nottingham pits, overall, chose not to strike due to the manner in which the work stoppage was called by the NUM. Some Black miners, when interviewed by historian Gary Morris, said that they did not feel able to strike without the majority of their white colleagues doing so – that as a minority, they had to conform to the majority decision. Former NUM organiser, John Robinson, who did strike, also explained that as they were individually identifiable in a majority white profession, they would be more vulnerable to police violence and ‘special treatment’ if they picketed.

“If the policemen had seen me at the front, [a black man], you can just imagine how they would have hit me. […] After the 1972 strike, I said I was never going on a picket line again.” – Fitzherbert Taylor, Black coal miner.

Black strike supporters from London, calling themselves the ‘Black Delegation’ visited Geddling pithead to try and get Black workers to strike, but they were unsuccessful.

Some Black and Asian miners who urged their own communities to support the strike, like Jim Hussain, an Asian miner born in Nottingham, were attacked as ‘race traitors’. Like Mark Ashton and LGSM, organisers of Black Support Groups found themselves questioned about what support the miners gave to Black and Asian causes.

“When we went into the mining communities, we recognised that they were just like us, fighting for their livelihood and fighting for their communities.” – Mukhtar Dar, Sheffield Asian Youth Movement (AYM).

This question fundamentally failed to understand the central concept behind many of the organisers belief systems – that solidarity did not necessarily need to be entirely reciprocal for it to be vital work to engage in. Many believed that the government breaking the strike would break the entire working class, which included LGBTQ+ and Black and Asian communities, so by defending miners, they were defending all working class people.

“When you think about it, it is quite illogical to actually say ‘Well, I’m gay and I’m into defending the gay community, but I don’t care about anything else.’ It’s ludicrous! It’s important that if you’re defending communities then you’re also defending all communities, not just one, and that’s the main reason I’m involved.” – Mark Ashton, LGSM.

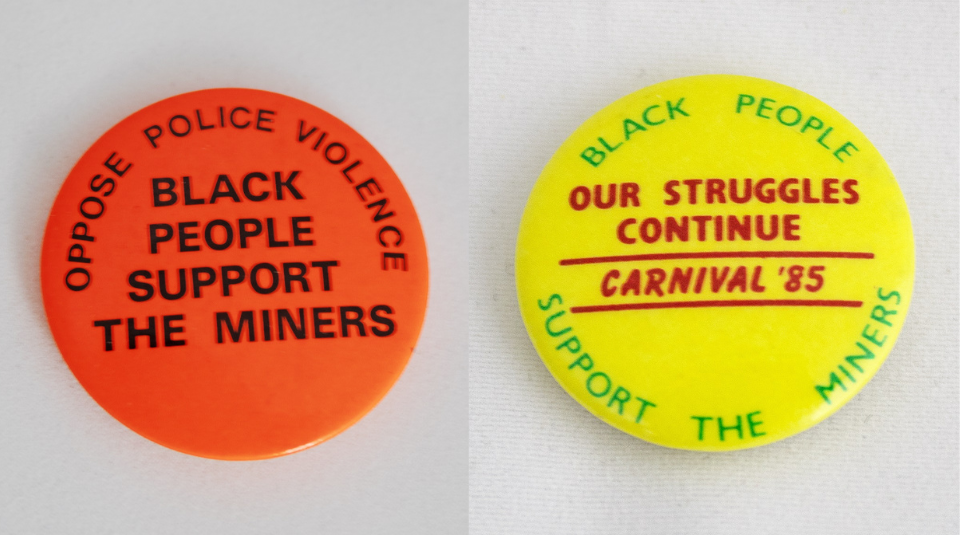

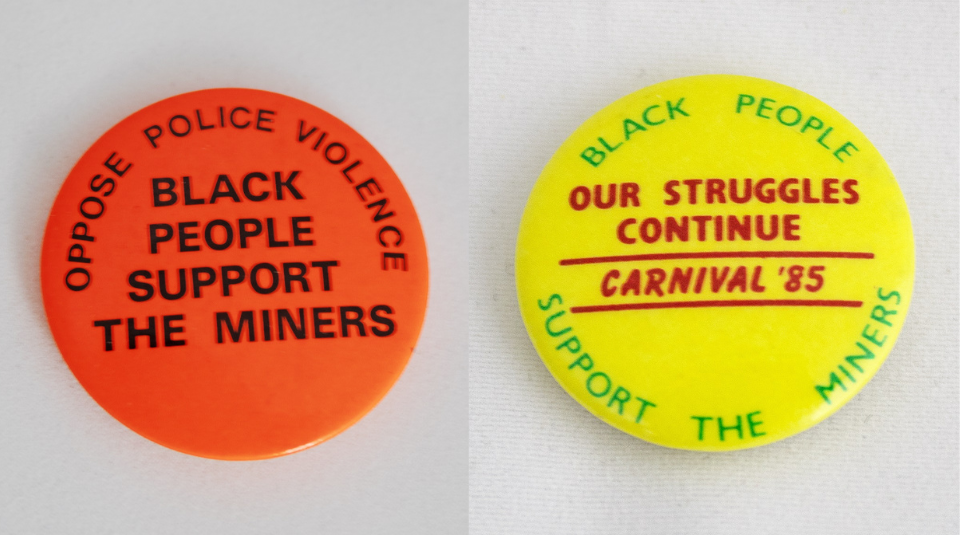

LGBTQ+ and Black and Asian solidarity campaigners recognised that miners were being faced with similar oppression tactics from the state, the police and the press, and tried to emphasise that to their communities. The Miners’ Strike took place at the same time as Black and Asian communities were being violently harassed by the police. The Brixton Riots took place six months after the end of the Miners’ Strike. Material produced by the Black community in support of striking miners highlighted police violence as a shared experience, as shown in the badges below.

Community celebrations, like London Pride and the Notting Hill Carnival, were key fundraising opportunities. Black miners who travelled from Nottingham for Carnival, like Ainsley, a Black Nottingham miner, were surprised to see how generous the community in London was. This generosity was especially shocking to him when he discovered that the Notting Hill crowds greeted him with surprise, as many in the crowd didn’t know there were any Black miners in the UK.

LGSM’s committee meeting minutes, held in the People’s History Museum archive, document that not only was there an emphasis on solidarity with the miners, the work to secure that was often done in collaboration with Black and Asian organisations. Although, the importance of diversity and identity compared to class was disputed, depending on members’ political affiliation, as some felt that class mattered above race, gender or sexuality.

“This goes to the heart of the political differences in LGSM. The CP [Communist Party] approach was to talk about two communities, both under attack from the government. Gay people and miners are both attacked by the police. Good solidarity. For us on the Trot side, we talked much more about class. Gays and miners were working class, if the miners lose, all working class people will suffer.” – Ray Godspeed, LGSM.

Black and Asian and LGBTQ+ organisers formed personal and often lasting relationships with mining communities, in some cases introducing miners to marginalised people for the first time, humanising rather than othering them. This led to profound changes in perspective for some of these miners, who went on to reciprocate the solidarity they had been shown – most notably campaigning against the anti-LGBTQ+ law Section 28, and to push the Labour Party to include Lesbian and Gay rights in their party conference the year following the strike. Without the block voting by the NUM, the motion would have failed. LGSM member Jonathan Blake draws a direct line from the NUM’s solidarity towards LGBTQ+ people, to the introduction of civil partnership rights in 2004.

“You have worn our badge ‘Coal Not Dole’ and you know what harassment means, as we do. Now we will support you. It won’t change overnight, but now a hundred and forty thousand miners know… about blacks and gays and nuclear disarmament and we will never be the same.” – Dai Donovan, Onllwyn miner, NUM.

Author:

Jaime is an oral historian with a focus on 20th century LGBTQIA+ community activism in the UK and Ireland. Their work has included recording LGSM member Jonathan Blake’s life story for archive, the Giz A Job project documenting oral histories of the 1981 People’s March for Jobs, and their ongoing work on 1980s HIV activism is soon to be presented at the UK Disability History and Heritage Hub conference. At PHM, they work to catalogue and care for the museum’s permanent collection and research collection objects hidden histories to bring new perspectives to the fore.