As part of People History Museum’s (PHM) current programme exploring migration, the museum commissioned a virtual LGBTQIA+ history tour focusing on the themes of race, migration and Empire from refugee rights campaigners Prossy Kakooza and Maggy Moyo, and PHM Community Curator Jenny White. In this blog post Jenny explores how colonialism influenced ideas about gender roles and sexuality in Britain.

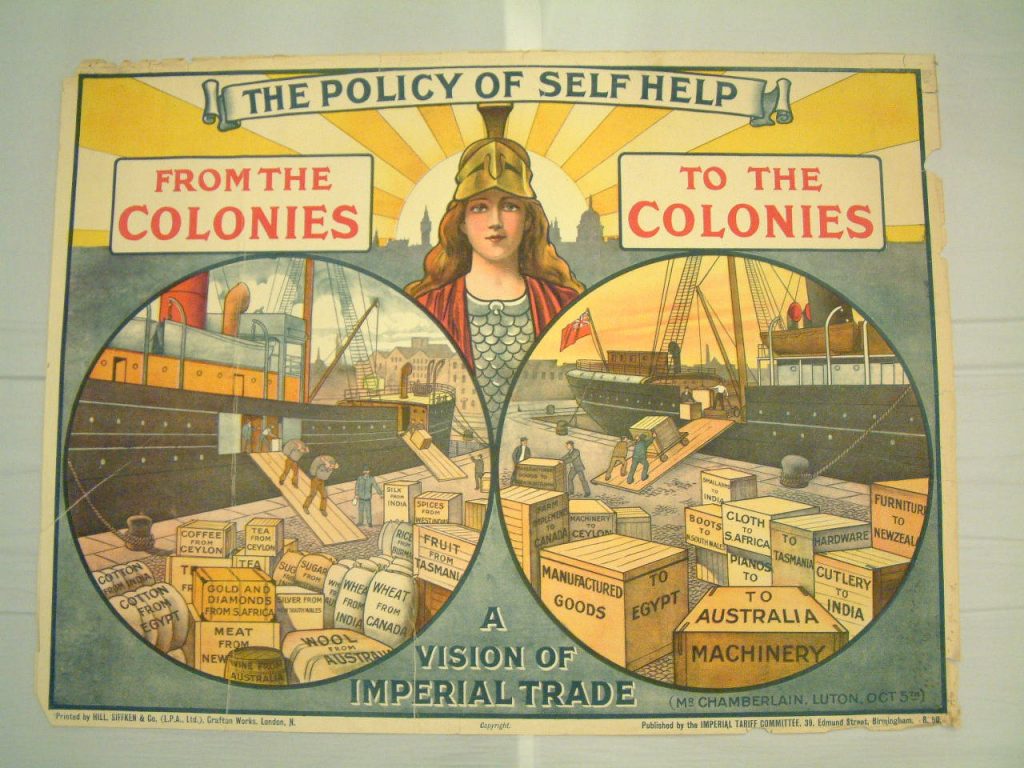

This poster promotes a vision of imperial trade, the transport of goods back and forth across the British Empire. The circular flow also neatly illustrates the impact of colonialism on LGBT+ history. Britain exported laws outlawing same sex acts and gender variance to the Indian Subcontinent, Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Changes in the population, and anxieties that there were not enough healthy men to defend the Empire influenced cultural attitudes and laws relating to homosexuality and gender within Britain.

Towards the end of the 1800s the British Empire spanned over 11.5 million square miles and included 345 million people. There was just no way for it all to be policed with armies on the ground, so it was important to promote a sense of English superiority.

Evolutionary theory had been used to justify British imperialism and the domination of ‘less civilised’ societies. Now Britain’s ruling classes began talking of the threat of ‘lower races’ within England, a degenerate urban poor dragging the country down and threatening its imperial vision.

There were concerns about a class of effeminate elites contaminating the nation’s morals and sullying Britain’s image on the international stage. A gay sex scandal involving Frederick / Fanny Park, Ernest / Stella Boulton and MP Lord Arthur Clinton influenced the tightening of anti gay laws in 1885. Previously men could only be prosecuted for sodomy or attempted sodomy, now a whole range of same sex behaviour was criminalised.

Anxieties over Britain’s moral and racial decline led to the promotion of very rigid gender roles – an English man should have a stiff upper lip, a sense of courage and honour, and be ready to defend the empire. A woman’s role was to preserve and improve the British race by breeding fit and healthy specimens.

In the early 1900s a number of welfare, heath and schooling initiatives were introduced to maintain the size and character of the population. Sporting activities were seen as a way of channelling sexual energy. War stories were all the rage – preparing boys to defend the colonies. It was in this context that Baden Powell, a Lieutenant general in the British army who had served in India and Zimbabwe, set up the scouting movement.

In 1861 Britain introduced its first imperial anti-gay legislation in India. Over the next forty years, laws criminalising sexual intimacy ‘against the order of nature’ were exported across our empire. Behaviours which challenged British notions of a strict gender binary were also prohibited.

These new regulations didn’t reflect the cultural values of the communities they were imposed on. A key aim was to supposedly protect white soldiers and settlers from being ‘corrupted’ by indigenous peoples. Our British ancestors saw the suppression of sexual and gender diversity as a civilising mission – their insistence that that the ‘natives’ lack morals, the women have no modesty, that men dress in ‘women’s’ clothes fuelled a desire to impose order.

There’s lots of evidence that pre-colonial cultures across Asia, Africa, the Americas and Australia acknowledged and accepted same sex intimacy and people of a third gender. Many societies worshipped androgynous deities who were seen as both or neither male and female. Ancient rock paintings by the San people of Southern Africa depict men having sex with other men.

In the 1880s and 90s King Mwanga ruled Buganda, now part of modern Uganda. He had 16 wives, but also a harem of men. He murdered Christians who were trying to rescue men from his harem, and executed men who refused to sleep with him after being influenced by missionaries.

In colonial India, the British introduced laws to eradicate hijras – people assigned male at birth but who lived as third-gender and had well defined, and permitted, religious and social roles. The hijra community prevailed, but in modern India face marginalism, a legacy of their reduced status under colonialism.

In 1967 gay male sex was partially decriminalised in England and Wales. However this was after the British Empire had been dismantled. The Church of England was supportive of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, arguing that what may be a sin should not necessarily be considered criminal. In debating the passage of the law many MPs questioned why homosexuality was criminalised but adultery ignored by the law.

Today out of the 53 countries in the Commonwealth of Nations – mostly former British colonies – 36 outlaw LGBT+ lives due to the legacy of colonial era legislation and Victorian missionary work. In many countries the political and social influence of evangelical Christian churches helps to fuel homophobia and maintain the status of same sex intimacy as both a sin and a criminal act.

The Scottish Independence Referendum campaign poster (pictured above) promotes the idea that that UK embassies campaign for LGBTQIA+ rights around the world. However, there are concerns about Western people parachuting into cultures they know little about, playing saviour and portraying people who do not share their beliefs as ‘uncivilised’. Clumsy interventions can fuel the idea that Western nations are once again trying to impose their cultural values.

It’s so important to listen to the LGBTQIA+ activists on the ground about the type of support that would be most useful. Change is happening – in 2018 India decriminalised same sex intimacy; in 2019 a high court challenge by a student in Botswana led to the scrapping of a colonial era anti-gay law.

Activists from communities colonised by Britain highlight that homophobia rather than homosexuality is a Western import, and are working to educate people about how gender identity is viewed in their traditional cultures.

The UK could do more to help LGBTQIA+ people fleeing persecution in their country of origin. People seeking asylum currently have to navigate a very harsh immigration system and combat a culture of disbelief. The Movement for Justice (MFJ) banner pictured above was made in 2010 by Ed Hall. It had its first outing at London Pride that year and was then taken to demonstrations at immigration court hearings, community events, and public hearings where MFJ put the immigration system on trial and people testified to their experiences.

Jenny White was one of nine PHM Community Curators who researched and designed the museum’s award winning 2017 exhibition Never Going Underground: The Fight for LBGT+ Rights (25 February – 3 September 2017). Jenny recently contributed to BBC Sounds Gaychester podcasts on Harry Stokes (1799-1859) and Manchester’s 1880 ‘drag’ ball. As a member of the Warp & Weft, Jenny helped transform statues of men in Manchester Town Hall into celebrations of local historical women, inspiring a campaign for a permanent statue of a woman.

Maggy Moyo is a social justice campaigner who advocates for the rights of migrants from marginalised backgrounds, including LGBT+ people. Maggy currently works for Right to Remain as the Manchester organiser for These Walls Must Fall (TWMF) campaign, a network of community-based campaigners who are part of a movement to end immigration detention in the UK.

Prossy Kakooza sought asylum on the basis of sexuality and currently works for British Red Cross supporting refugees and asylum seekers. Prossy is a campaigner and on the advisory board of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Claims of Asylum (SOGICA) research project on the experiences of LGBTQI+ people; claiming international protection on basis of sexual orientation and gender identity in Europe.

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM.

Watch a full recording of the Migration, Race & Empire: LGBT+ histories tour, at People’s History Museum with Maggy Moyo and Jenny White.

Read This Alien Legacy, The Origins of “Sodomy” Laws in British Colonialism; listen to BBC Radio 4’s Out in Africa’s Charles Adesina exploring the legacy of anti gay colonial laws, and what it means to be gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender in Africa today.