Over the past year, our Collections Team have been conducting a project to research our extensive poster collection, thanks to funding from Arts Council England’s Designation Development Fund. Many of the posters they’ve found explore Black History. In this blog, PHM’s Collections Assistants Shivaya Prasad and Kayleigh Crawford are sharing some of the poster highlights as part of Black History Month.

Black History Month is a celebration and recognition of Black, African and Caribbean culture, art, history, and contributions. It was first celebrated in the UK in the 1980s. Richard Benjamin discusses how Black History Month helps dispel racist ideas, and offers more opportunity to learn about Black History, particularly in a time when such history is not mandatory in the British National Curriculum.

The Black History Month UK website states the theme for 2022 is ‘Time for Change; Action Not Words’: “It is not just a month to celebrate the continued achievements and contributions of Black people to the UK and around the world. It is also a time for continued action to tackle racism and reclaim Black History.” While we are highlighting these posters now, the aim of the project is to allow us – and you – to know our collection better, and share these stories all year round.

![]()

OSPAAAL emerged from the Tricontinental conference that united revolutionary movements from Africa, Asia and Latin America. It aimed to be a bridge across different anti-racist, anti-imperial and anti-capitalist movements. Black Panther leader Stokeley Carmichael called the Tricontinental magazine, which was published as OSPAAL’s main transnational communication tool until 2019, “A bible in revolutionary circles.”

OSPAAAL’s posters and work are all about international solidarity and calling for action. They utilised their art for many causes such as liberation across the African continent and solidarity with African-American people. They worked with artists internationally, such as Emory Douglas, a Black American revolutionary artist who was a member of the Black Panther Party, until it disbanded in the 1980s. The Black Panthers supported the organisation further through articles and art.

Angela Davis is an American activist, philosopher, feminist, and scholar. The above poster was issued by the Angela Davis Defence Committee in London, in solidarity with Davis, calling to free her from a racist and unjust arrest and trial in 1970. During George Jackson’s trial, guns that Davis purchased legally were used in an ‘attempted courthouse escape’, which resulted in the deaths of the hostage judge, the 17 year old Black gunman, and the two Black defendants. She became a fugitive from the FBI and was put on their Ten Most Wanted Fugitive list. Davis was arrested and incarcerated, charged with kidnapping and murder.

National and global campaigns and protests were organised to free her from prison. This led to the Free Angela Davis campaign and an international Angela Davis Defence committee across America and 67 other countries. After 16 months, she was released, on a not guilty verdict as her ownership of the guns used in the crime did not justify accusing her of the crimes committed.

Davis went on to pursue anti-racist, socialist, communist and feminist activism. She has written several books on the prison industrial complex, Black feminism, and politics.

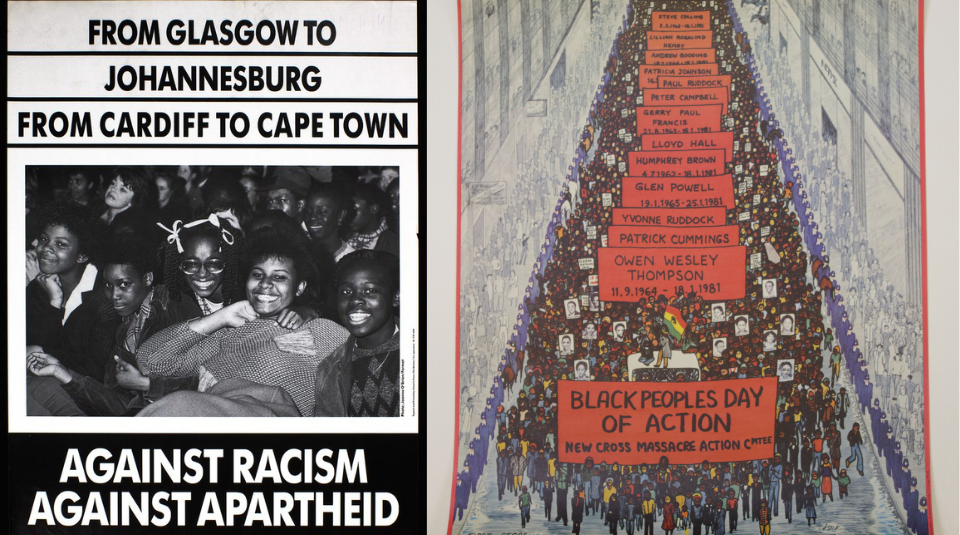

The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) opposed South African apartheid; a system of institutionalised racial segregation that ensured that the country was dominated politically, socially and economically by the minority white population. The movement began as the Boycott Movement in 1959, asking British people not to buy South African goods. The boycott gained widespread support from students, trade unions, and the Labour, Liberal and Communist parties.

In 1960 the group was renamed the ‘Anti-Apartheid Movement’ following the Sharpeville massacre, when 69 unarmed protestors were shot dead by South African police, and the movement chose to move beyond simple boycotts. The AAM led protests and vigils, including a 72-hour vigil outside the Commonwealth Secretariat venue in 1961 that led to South Africa being expelled from the Commonwealth. They also aimed to encourage economic sanctions. The AAM grew into the biggest British pressure group on an international issue and operated until 1994, when South Africa held their first democratic elections.

Boycotts and sanctions have a long history as a form of protest. AAM’s campaign to ban imports of South African coal attracted a lot of support within Britain and gained a high degree of influence with trade unions as well as within political circles. This poster was made in collaboration with the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and together the two organisations rallied massive support for the initiative. By targeting coal, South Africa’s second largest import, the campaign aimed to put financial pressure on the South African government so that apartheid became an untenable policy. The movement is now widely regarded as having helped contribute to the end of apartheid in South Africa and its success is now often cited as an inspiration for similar campaigns across the globe.

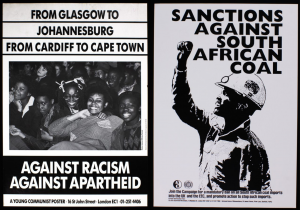

This poster from the New Cross Massacre Action Committee (NCMAC) depicts a demonstration in London on 2 March 1981 attended by 20,000 people who marched over a period of 8 hours from Fordham Park to Hyde Park. The crowd is raising the portraits of the 13 victims of the New Cross Massacre. Many had placards that said “13 Dead, Nothing Said.” The organised march was named the ‘Black People’s Day of Action.’

The NCMAC was formed on 20 January 1981, within two days of the firebombing of the home of a Black family in Lewisham in a suspected racist attack. The fire took place during a birthday party for Yvonne Ruddock and Angela Jackson. 13 people died, aged 14 to 22, and the tragedy was called the New Cross Massacre. All the victims were Black. Another victim is believed to have committed suicide two years later due to the trauma of the fire. The NCMAC started to mobilise and encourage protest against the government’s indifference, the distorted media coverage and what is believed to be the police’s biased treatment of the fire.

The case remains an open verdict, and a memorial was built for the victims of the fire in Lewisham in 1997.

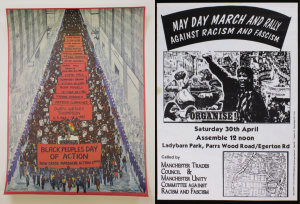

Manchester Trades Union Council (TUC) and Manchester Unity Committee Against Racism and Fascism organised a march and rally against racism and fascism. Equal rights for Black workers is a topic that is often overlooked when discussing the history of workplace rights and trade unionism. According to a recent report by the TUC, Black workers have been historically underrepresented in trade union membership due to discrimination within unions themselves. The contributions of Black workers to the trade union movement also remain undervalued and largely undocumented, even though organisations such as the Black People’s Alliance were campaigning for workers’ rights alongside many larger unions.

From the late 1970s onwards, trade unions have steadily become more involved with anti-racist work and this poster is therefore a significant addition to our collection as it shows trade union solidarity with Black workers and presents workers of colour at the forefront of trade union organising.