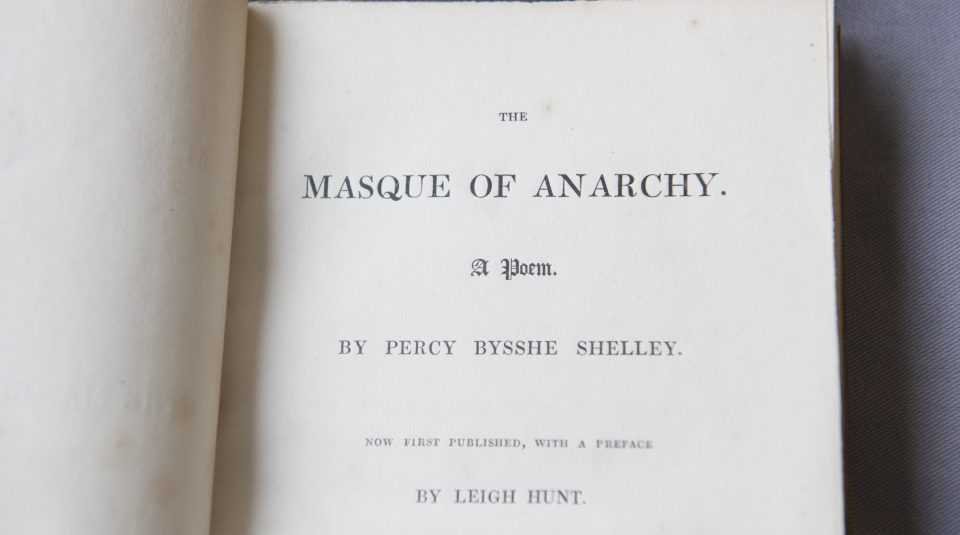

To complement the display of a first edition of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s The Masque of Anarchy from Friday 1 March until the end of April 2019, we invited Dr Michael Sanders, Senior Lecturer in 19th century writing at the University of Manchester to share his insight into Shelley’s protest poem.

In his blog Michael reveals his first encounter with the poem on a record sleeve:

‘Rise like lions after slumber

In unvanquishable NUMBER!

Shake your chains to earth, like dew

Which in sleep had fall’n on you:

YE ARE MANY — THEY ARE FEW. —’

Lines 151 to 155 from The Masque of Anarchy by Percy Bysshe Shelley.

‘The closing stanza of Shelley’s The Masque of Anarchy are amongst the most famous lines of political poetry ever penned by an Englishman abroad. In 2017 they featured prominently in the Labour Party’s general election campaign, being quoted frequently by the leader of the Labour Party Jeremy Corbyn, as well as inspiring the title of the party’s 2017 manifesto, For the Many, Not the Few. In quoting Shelley’s words, Corbyn was continuing a tradition which is now almost 200 years old. Ever since their publication in 1832, Shelley’s words have been cherished by the left; from the Chartist movement of the 1840s through the socialist pioneers of the 1880s and 1890s and beyond, Shelley’s call to resistance has echoed down the decades.

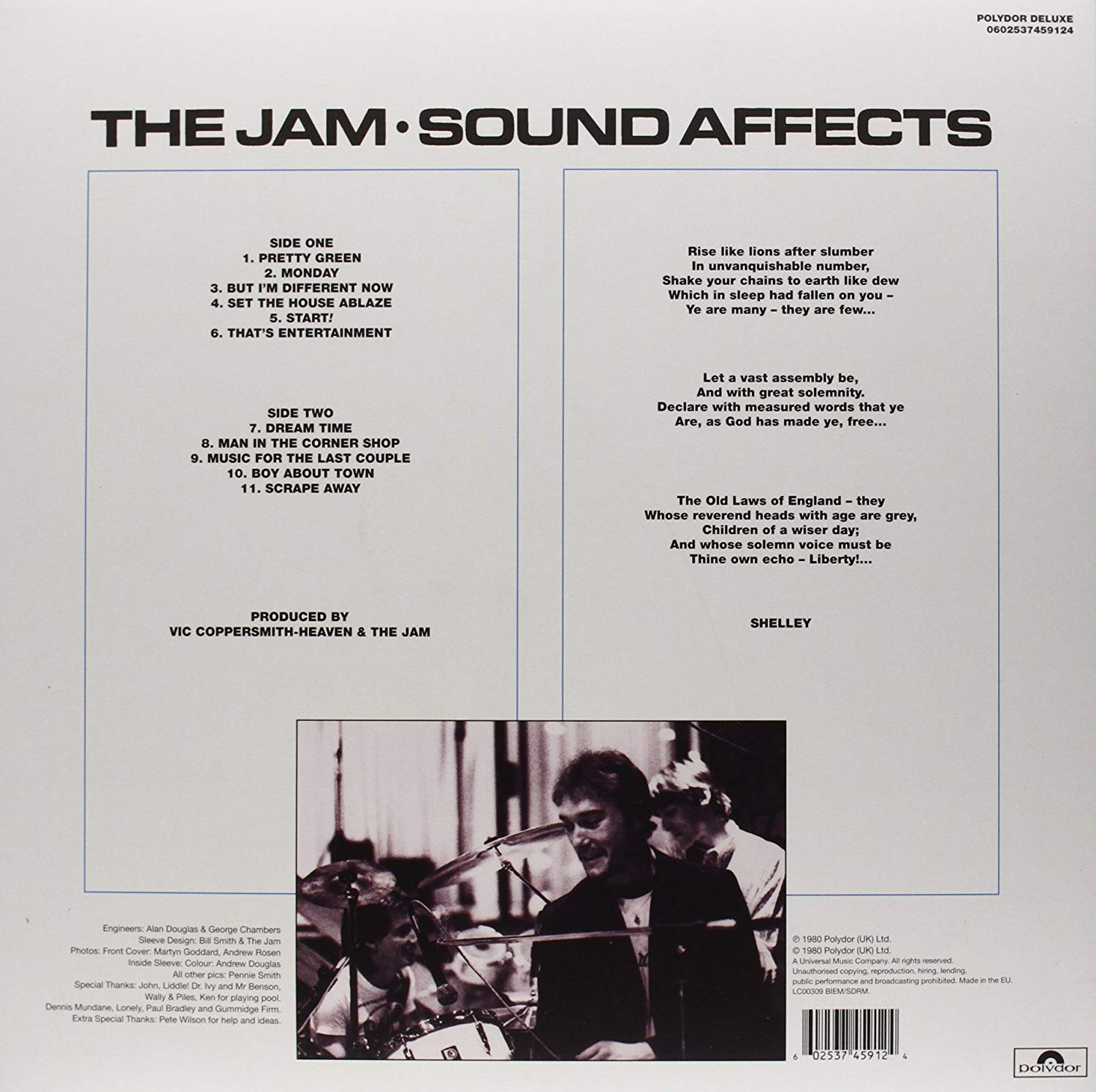

However, my first encounter with these lines was not on a demonstration or in a political meeting but in a record shop. I first read them, in 1980, on the back sleeve of The Jam’s newly released Sound Affects album. In fact, the album quoted 13 lines from the poem, giving stanzas 73 and 82 in addition to its final verse. Although the album cover attributed these lines to ‘Shelley’, it didn’t say where they came from. At that time the only Shelley I had heard of was Pete Shelley (of English punk rock band Buzzcocks fame) and I didn’t think this was quite in his style. So a few days after purchasing the album, I headed off to a secondhand bookshop, found a cheap edition of Shelley’s Selected Works and finally found that the lines were taken from The Masque of Anarchy. My teenage self reckoned that if The Jam’s Paul Weller (and PHM Radical) rated this guy Shelley then it was probably worth reading the whole poem. So began a lifetime’s interest in English radical poetry.

The Masque of Anarchy was written in response to the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester on 16 August 1819. Percy and Mary Shelley were living in Italy when news of the events in Manchester reached them and Mary later recalled ‘when the news of the Manchester Massacre reached us; it roused in [Shelley] violent emotions of indignation and compassion…Inspired by these feelings, he wrote The Masque of Anarchy’ (Note on The Mask of Anarchy, by Mrs Shelley, 1839). On completing the poem, Shelley sent it to his friend Leigh Hunt, editor of The Examiner, for publication. Leigh Hunt decided against publishing the poem, later claiming he ‘thought that the public at large had not become sufficiently discerning to do justice to the sincerity and kind-heartedness of the spirit that walked in this flaming robe of verse’ (Preface to The Masque of Anarchy, 1832).

It is possible that in the atmosphere of intensified political repression following Peterloo, Leigh Hunt was reluctant to risk a further period of imprisonment (he had already served two years in jail for criticising the Prince Regent in The Examiner). Thus, the poem never appeared in print during Shelley’s lifetime. Indeed, it was first published in 1832, ten years after his death, by Edward Moxon with a preface by Leigh Hunt. A copy of a first edition of the poem has been purchased by the Working Class Movement Library (WCML) thanks to funding from The National Lottery Heritage Fund Collecting Cultures programme, and will be displayed at both WCML and PHM as part of the Peterloo bicentenary commemorations.

It is appropriate that this volume will be on display first at People’s History Museum because Shelley wrote this, consciously and deliberately, for the people. For The Masque of Anarchy Shelley adopts the popular form of a broadside ballad. He uses a direct, forceful style which is very different from his more abstract, philosophical musings of poems such as Mont Blanc or Hymn to Intellectual Beauty. Shelley’s anger at and contempt for the government which had presided over Peterloo is unmistakable; his image of the Prime Minister, Lord Castlereagh, ‘toss[ing] human hearts’ to his ‘blood-hounds’ is as savage and visually arresting as any cartoon by Steve Bell or Martin Rowson. Just like these present day cartoonists, Shelley’s intention is to get his readers to see what is really happening. In this instance, that those same politicians who proclaim their obedience to the law and the constitution are in reality the agents of anarchy. How else, Shelley asks, could you describe the murder of unarmed, peaceful demonstrators at St Peter’s Field?

But The Masque of Anarchy does more than simply record Shelley’s anger. It also looks to redeem the suffering inflicted on the people at Peterloo. The poem does this in two ways; it turns Peterloo into a prophetic sacrifice which brings about a new social order, and it also imagines a second Peterloo which ends with the victory of the people. Shelley insists that only freedom, not revenge, can atone for the blood spilt at Peterloo. And the freedom he depicts starts with the material, bread and butter freedom that comes only when labour receives its proper reward:

‘For the labourer thou art bread,

And a comely table spread

From his daily labour come

In a neat and happy home.

Thou art clothes, and fire, and food,’ (lines 217 to 221).

In the verses which follow Shelley identifies, ‘Justice…Wisdom…Peace…[and] Love’ (lines 230 to 246), as the key attributes of freedom.

However, in order to secure these blessings, the people will once again have to resist oppression as they did at Peterloo. The poem’s final third begins ‘Let a great Assembly be / Of the fearless and the free’ (lines 262 and 263). Shelley then calls on that same Assembly to ‘Declare with measured words that ye / Are, as God has made ye, free’ (lines 297 and 298). This is Peterloo reimagined: a gathering of the people to assert their political rights. Shelley is under no illusion how the powerful will respond to such a demonstration. He warns that the ‘tyrants’ will, once again, use violence – the ‘fixed bayonet’ will again draw ‘blood’, and ‘the horsemen’s scimitars’ will ‘Wheel and flash’ (lines 311 to 316). In the face of such aggression, Shelley advocates non-violent resistance:

‘Stand ye calm and resolute,

Like a forest close and mute,

With folded arms and looks which are

Weapons of unvanquished war’ (lines 319 to 322).

Shelley prophesises that the aggressors will lose all moral authority, ‘they will return with shame / To the place from which they came’ (lines 348 and 349) and with their departure in disgrace the stage of history is set for those triumphant closing lines which, as Shelley himself predicts, will be ‘Heard again — again — again —’:

‘Rise like lions after slumber

In unvanquishable NUMBER!

Shake your chains to earth, like dew

Which in sleep had fall’n on you:

YE ARE MANY — THEY ARE FEW. —’

Dr Michael Sanders is currently working on the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) funded research project, ‘Piston, Pen & Press’. Find out more:

Available now, The Poetry of Chartism, by Dr Michael Sanders

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM.

The Masque of Anarchy was purchased by the Working Class Movement Library (WCML) in Salford using funding from The National Lottery Heritage Fund Collecting Cultures programme. It will be on display at PHM from Friday 1 March 2019 until the end of April 2019 as part of PHM’s year long programme exploring the past, present and future of protest, marking 200 years since the Peterloo Massacre; a major event in Manchester’s history, and a defining moment for Britain’s democracy. It will then return to WCML, for display from Friday 31 May 2019 until Thursday 19 September 2019 in their exhibition Peterloo: news, fake news and paranoia.

A copy of The Masque of Anarchy will also be on display from Thursday 21 March until Sunday 29 September 2019 at The John Rylands Library’s exhibition Peterloo: Manchester’s Fight for Freedom. You can also view the Masque of Anarchy poem in their online collection.

PHM and the WCML have been working in partnership on a project funded by The National Lottery Heritage Fund Collecting Cultures programme entitled ‘Voting for Change – 150 years of radical movements, 1819 to 1969’. This project has enabled PHM and the WCML to make significant acquisitions of objects and archive material related to movements and campaigns for the right to vote, from the build up to the Peterloo Massacre in 1819 to the lowering of the voting age in 1969.

Part of PHM’s year long programme exploring the past, present and future of protest, marking 200 years since the Peterloo Massacre; a major event in Manchester’s history, and a defining moment for Britain’s democracy.

People’s History Museum is open seven days a week from 10.00am to 5.00pm, and is free to enter with a suggested donation of £5. Radical Lates are the second Thursday each month, 10.00am until 8.00pm.