It has been over a century since the first recorded anti-fascist action in the UK, when anti-fascist Communist Party of Great Britain activists disrupted the inaugural meeting of ‘British Fascisti’ on 7 October 1923. People’s History Museum (PHM’s) Collections Assistant Jaime Starr puts the spotlight on key modes of British anti-fascist resistance from the past and present.

Fascism is a far right, ultranationalist political ideology that originated in 1920s Italy. The Nazis in Germany were another example of a fascist government. British fascist groups were founded as early as 1923, the first being ‘British Fascisti’, later known as ‘British Fascists’. The main groups we discuss in this blog are the British Union of Fascists (BUF) which operated from 1932 to 1940, the National Front (NF), which was founded in 1967, and the English Defence League (EDL) founded in 2009. Fascist figures were often involved in more than one group, and membership overlap is common.

British fascists were inspired by Italian and German fascism, but British fascist politician Oswald Mosley, who led several British fascist organisations from the 1930s onwards, claimed they were also acting in the legacy of Oliver Cromwell, naming Cromwell’s rule in the 1650s as England’s ‘first fascist age’. Fascists claim that the nation they live in is under threat and declining, often blaming this decline on changing demographics in society. Over the years, fascists have blamed social decline on women entering the workforce after the First World War, society’s growing tolerance of LGBTQIA+ people, and religious minorities like Jews and Muslims, but their main target has always been immigrants.

As migration patterns in the UK have changed, the identity of migrants that fascists target has changed. In the 1920s to 1940s fascist parties blamed Jewish people for Britain’s so called decline. As post war migration from majority Black British colonies took place, fascist attention shifted to focus on Black and Asian communities, and today’s fascists primarily target migrants from Muslim communities.

Anti-fascists don’t necessarily belong to a particular group or political party – anti-fascism is any action undertaken to oppose fascist activities. Examples of anti-fascist action could include going on an opposition march, intervening in hate attacks to protect a victim, donating money or time to groups dedicated to resisting fascists, offering to guard a mosque that has been threatened with attack, or creating information resources to dissuade people from supporting fascists. You can find further examples of anti-fascist actions, and the people and groups who took part in them below.

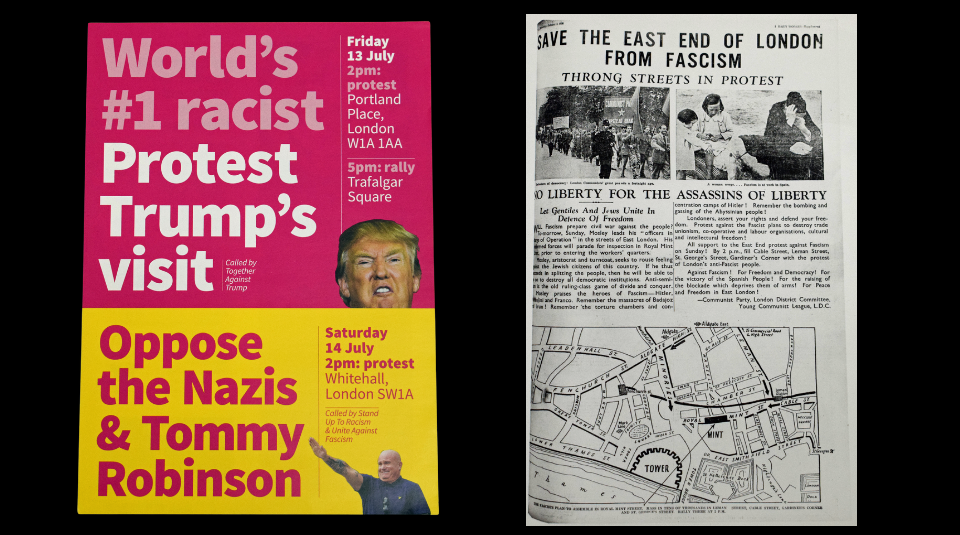

Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists (BUF) was highly militaristic, wearing ‘blackshirt’ uniforms, and during the early 1930s BUF members would march through neighbourhoods with Jewish and migrant populations to intimidate them. On 4 October 1936, the BUF arranged a march through the East End of London, which was home to almost half of Britain’s Jewish population.

100,000 people, including the mayors of the five east London neighbourhoods affected, had signed a Jewish People’s Council petition calling for the march to be banned, but the Home Office refused to do so, instead sending 7,000 Metropolitan police to protect the 2,000 to 5,000 BUF members attending from between 100,000 and 310,000 anti-fascist counter demonstrators. The estimated numbers of people who participated on each side vary depending on who reported on the day. Among the anti-fascists were scores of local residents, members of the Communist Party of Great Britain, the Independent Labour Party, and the Jewish Ex-Servicemen’s Movement Against Fascism – a group of decorated First World War veterans, who the police attacked, destroying their Royal British Legion standard in the process. While London’s Muslim population at the time was small, a group of Muslim sailors from Somalia joined the anti-fascist ranks while on shore leave. This was widely celebrated as an important interfaith solidarity gesture.

Protesters adopted the Spanish anti-fascist civil war slogan ‘No Pasarán!’ which means ‘They shall not pass!’ and built barricades on Cable Street in Wapping, east London, to try and physically block the fascist march from passing. Anti-fascists physically fought BUF members to try to drive them out of the area and were violently attacked by the police and the BUF. Despite the police violence, the anti-fascists were successful in their goal as police forced Mosley and his supporters to leave the East End. The Battle of Cable Street, as it became known, was a widespread community response to fascism, and is often celebrated by antifascists as a moment of victory against British fascism.

The Public Order Act of 1936 banned wearing political uniforms and introduced the requirement to ask police permission for demonstrations to prevent a repeat of the Battle of Cable Street. The BUF was eventually banned in 1940 amid concerns that British fascists could potentially undermine the British government’s fight against Nazi Germany. Mosley and 750 other BUF members were imprisoned in interment camps to remove the risk of them working for the Nazis like former BUF member Lord Haw-Haw had. After the Second World War, Mosley launched a new fascist party called the Union Movement which absorbed many BUF members. The Jewish Ex-Servicemen’s Movement Against Fascism, a group of First World War veterans, was replaced by the 43 Group, a group of Jewish Second World War veterans who clashed frequently with Union Movement members wherever they attempted to gather.

Following the Second World War, it was harder for openly fascist organisations to get public support; the British public had fought a war against fascism, and emerging evidence of the Holocaust also tempered public opinion. Throughout the 1950s, groups like the League of Empire Loyalists (LEL) promoted antisemitic, racist, and fascist policies from within the Conservative Party. LEL members John Tyndall and Martin Webster formed the National Front (NF) in 1967, with a focus on anti-immigrant racism. The NF was the most active fascist movement in the 1960s and 1970s, campaigning for Black and Asian people to be deported from the UK, and for a ban on non-white immigration, and supporting the apartheid regime in South Africa. Members of the NF also campaigned for a ban on mixed race marriages. The NF worked hard to recruit working class white people, including within trade unions, by claiming that immigrants were going to take their jobs.

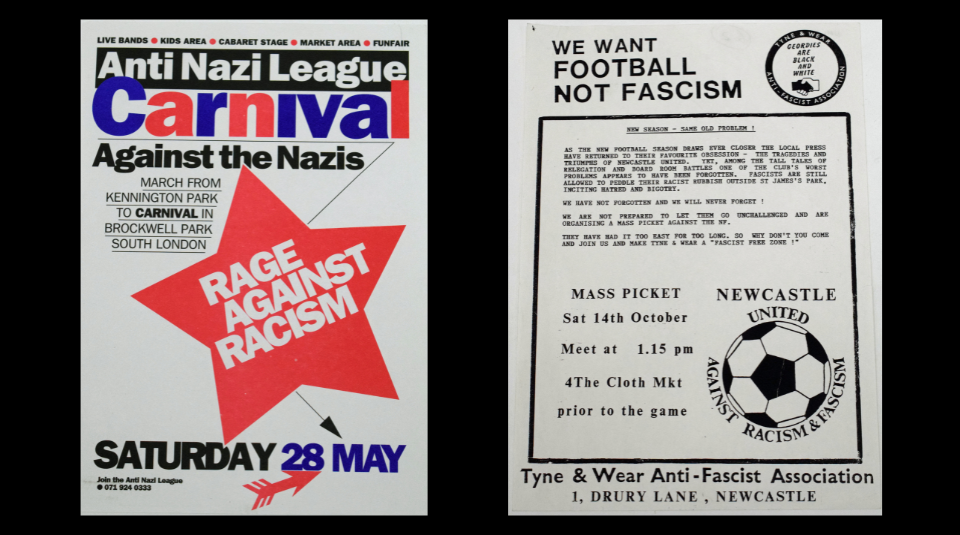

While initially the NF started as a political party, by 1976, a street action wing had formed, with 2,000 members. They sold newspapers at football matches full of sensationalist stories about violence by Black and Asian people and migrants, in attempts to radicalise the people who read them, and marched through Black and Asian neighbourhoods, like Brick Lane in London. Like the BUF in the 1930s, these marches were attempts to intimidate the minority groups that the fascists were now blaming for the decline of British society, and were met by efforts to prevent them, from anti-fascists who joined local residents from Black and Asian communities. Anti-fascists from the Socialist Workers Party, alongside others, formed the Anti-Nazi League (ANL), to organise opposition to fascist actions.

Celebrities like musicians David Bowie and Eric Clapton made racist remarks in public that made fascism sound appealing, which caused concern to anti-fascists, as these well known figures were highly influential to their young fanbases. In response, Rock Against Racism (RAR) was formed, a campaigning organisation hosting carnivals in London and Manchester to urge young people to reject racist and fascist politics, and to provide spaces where Black and white people could mix, united by their love of music. In response to the 2024 summer racist riots, Rock Against Racism has relaunched and is planning a series of concerts.

Football fans in the 1980s and 1990s organised to resist fascists selling their newspapers at football grounds. Football hooliganism had strong ties to the far right, and fascist football fans would racially abuse Black football players, even if they played for the team that person supported. On one occasion, Leeds United fans dressed up as members of the racist American hate group the Ku Klux Klan. Fans who opposed racism and fascism created anti-fascist fanzines to make it clear that not every football fan supported the acts of fascists in the terraces; the Leeds United ‘Marching Together’ zine on display in the Collection Spotlight case in Gallery One at PHM has cover art which shows the consequences the anti-fascist fans wish would befall the fascist fans.

Black footballers themselves also got involved in anti-fascist organising, with Newcastle United goalkeeper Shaka Hislop providing the funding to found ‘Show Racism the Red Card’ after he was racially harassed by Newcastle United fans who, on realising he was their team’s goalie, pivoted from cursing at him to asking for his autograph. Manchester United player Eric Cantona famously launched himself into the crowd to kick a National Front member who xenophobically abused him from the Crystal Palace stands in 1995. Cantona, whose grandfather was an anti-fascist veteran of the Spanish Civil War, claims this as his proudest moment as a footballer, and it is often seen as a turning point in football clubs’ willingness to protect their players from xenophobic and racist abuse.

Fascists aren’t always recognisable at first glance. Although some have specific tattoos, badges, or clothing which have symbols that can identify them as fascists, many choose not to call attention to themselves, as a way of infiltrating organisations – as the National Front did with trade unions in the 1970s in an attempt to convert people to their point of view. Anti-fascists produced badges with slogans on them so that the wearers could make it clear that they didn’t agree with fascist beliefs. Badge wording varied greatly and might have referred to the wearer’s profession, cultural identity, or a hobby.

Using badges to advertise the wearer’s rejection and disapproval of fascist and far right beliefs not only serves as a way to make clear to fascists that the wearer isn’t interested in joining them, but they can also be useful to show marginalised people that they have allies and supporters who reject divisive politics, and Islamophobic, antisemitic, racist, and xenophobic hate.

Today, most fascist and anti-fascist organising takes place online. During the summer of 2024, social media platforms were used by groups like the English Defence League, and high profile far right personalities like Tommy Robinson to organise fascist gatherings. This happened both on publicly viewable platforms like X and Facebook, and in secret on private messaging apps like Telegram and Signal. Anti-fascists today monitor the information shared by fascists on these platforms to plan responses. Digital calls to action are then used to create anti-fascist presence in the physical world.

For instance, a fascist produced list of over 100 legal firms across England to attack as they provided services to refugees was leaked from a fascist Telegram channel in August 2024. Anti-fascists used that list to organise pro-refugee, anti-fascist, and anti-racist counter demonstrations, and tens of thousands of people turned up, putting their bodies in the way of fascist attempts at intimidation. While the modes of organising have changed, the anti-fascist marches and demonstrations that drove fascist far right rioters from England’s streets during summer 2024 show that the historic methods of anti-fascist action are as relevant now as they were a century ago.

Visit the latest Collection Spotlight case in Gallery One, No Pasarán! A century of British anti-fascist action, on show until 31 March 2025.

Book an appointment to discover more of the museum anti-fascist material with the Archive Team via archive@phm.org.uk.

Read about the history and meanings of the raised fist symbol, adopted by anti-fascist movements between the world wars, using examples that include posters and photographs from People’s History Museum’s collection.