Ahead of PHM’s May Day Markets (Saturday 3 and Sunday 4 May, 2025) we’ve chatted to People’s History Museum researcher Dr Shirin Hirsch to find out more about the early May Day Bank Holiday and the intriguing history that led to it becoming a permanent fixture of the holidays in May. It’s also a reminder that May Day had to be constantly fought for from below.

The history of May Day stretches centuries, but it was only on 1 May 1978 that the first official May Day Bank Holiday took place, joining Scotland and the bulk of the world in marking International Workers’ Day. Sadly this was a cold and rainy day very unlike the traditional images that we associate the occasion with.

Michael Foot as Employment Minister had introduced the legislative change in 1976, although an increasingly anxious Labour Government then delayed its implementation for two years. Alongside the dreary weather, the media reports marking the new Bank Holiday were far from celebratory. The BBC focused on a Suffolk village where several shopkeepers had opened up in protest against May Day, or as they put it, against this kind of May Day. One shopkeeper explained: ‘We don’t want to be associated with Red Square, we want to be associated with Britain and the Queen and all that sort of thing, you know?… Just let’s have a May Day holiday but call it something else.’ But what, the reporter asked, was the true spirit of May Day?

There are long associations with spring, growth and fertility drawn from Pagan festivities for May Day. They are born out of these rituals from the land, however, it was the labouring masses who made an impregnable imprint on May Day. In a society in which workers were often ignored and their labour made invisible, for at least one day a year they could be celebrated, not patronisingly by others, but through their own actions. How the day was marked varied enormously but one thing was clear: May Day was not a time to work.

Yes, and not long after it was officially recognised. In 1982, weeks after the British victory in the Falklands War, a parliamentary bill was voted on to abolish the May Day Bank Holiday and for a new Bank Holiday to be selected more ‘in keeping with the traditions of England than the workers’ jamboree’ as the Conservative MP for Preston North, who was moving the bill, put it.

Opposing the bill was the Labour MP for Preston South who claimed that May Day had grown into a celebration of internationalism and that feelings had gained ground that communities should come together to make clear their unwillingness to be involved in inter-capitalist wars. He concluded that May Day was a ‘people’s holiday’ and long may it remain so.

The MP representing the Prestonians of the South was victorious. The bill to abolish the May Day Bank Holiday was defeated, narrowly.

In 1889 the first International Workers’ Day was officially proclaimed by the socialist Second International. This was to be a day of mourning for the Haymarket Martyrs of Chicago, anarchists who had protested for the eight hour day, who were then framed and executed by the state. As August Spies, one of those convicted, was led to his death, he called out: ‘There will come a time when our silence will be more powerful than the voices you strangle today!’

Spies was right. In mourning the dead and demanding the eight hour day, International Workers’ Day took off across the world. It became not just a day of anger and sadness, but also one of celebration and joy. In 1893 the Italian workers’ leader Andrea Costa explained on May Day: ‘Catholics have Easter – henceforth workers will have their own Easter’. Across the world workers’ movements organised annual stoppages of work, mass demonstrations and festivals.

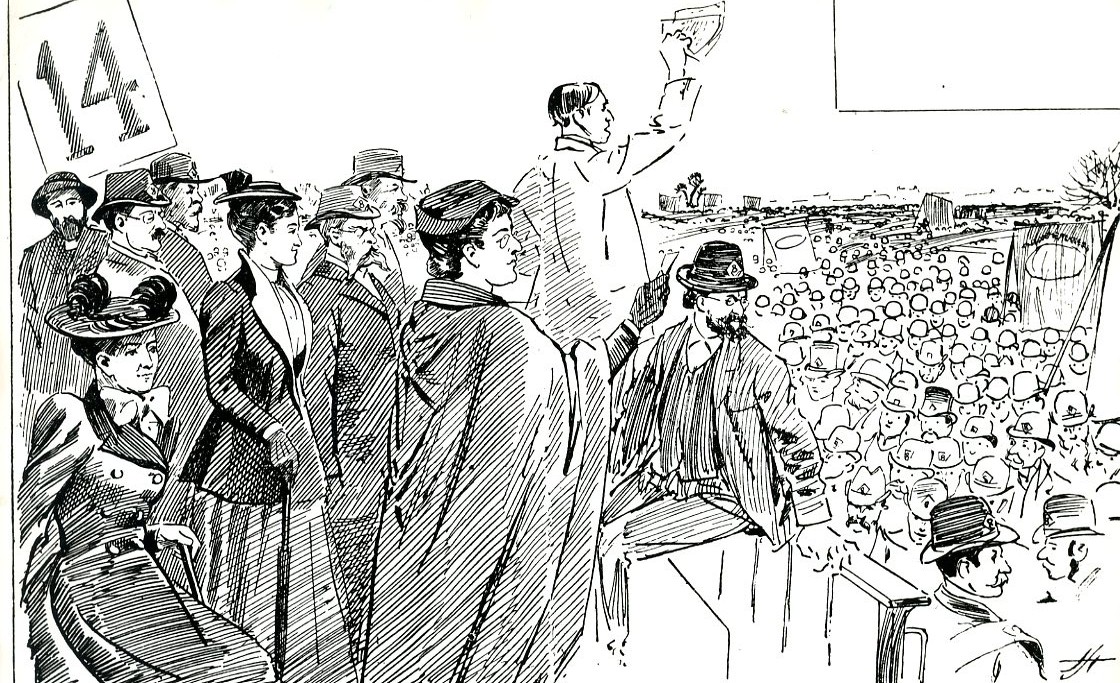

In Britain, the first May Day protests following the international call coincided with the heights of New Unionism, when huge numbers of workers demanded better working conditions. In Gallery One of the museum we tell the story of New Unionism, a movement that began with the Match Girls’ Strike in 1888 and sparked waves of strikes and mass unionisation among workers who had previously been ignored by the more respectable, almost exclusively male, craft unions. In the museum’s archive you can see drawings of the first May Day protests in Britain in Hyde Park where these new unionist workers flocked, 300,000 in 1890 demanding the eight hour day. Along with Engels, the socialist Eleanor Marx is on the platform, and in her speech to the crowd she proclaimed: ‘We have not come to do the work of political parties, but we have come here in the cause of labour, in its own defence, to demand its own rights’. Quoting Shelley, Eleanor Marx ended her speech with the famous ‘Ye are many they are few’.

May Day was popular when the workers’ movement was at its strongest. So, for example in 1919, the year in which Britain was perhaps at its closest to workers revolution, May Day was big and militant. In the museum’s archive you can see photographs of May Day marches through the decades, and it is noticeable that women and children are far more present in these images, with families often wearing their Sunday best for an important proletarian event. Of course, women’s presence did not mean their equality and in one May Day image from the 1930s you can see women marching behind a ‘Brotherhood of youth’ banner.

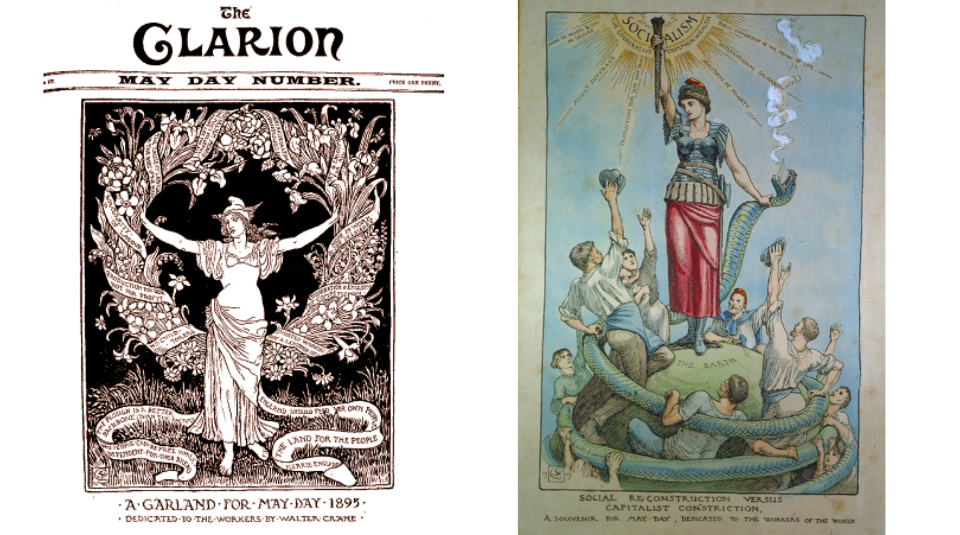

The radical historian Linebaugh argues that May Day has a green side and a red side. Green is a relationship to the earth and what grows from it, red a relationship to people and blood spilt. Green is creation of desire; red is class struggle. And May Day is both. The vision of this red and green May Day was most powerfully expressed through the socialist artist Walter Crane.

Crane’s influence upon the iconography of the labour movement was immense. Crane hated what the industrial revolution had done to workers’ lives, arguing that such machinery, while intended for the service of humanity, had ‘under our economic system enslaved humanity instead, and become an engine for the production of profits, an express train in the race for wealth…’ May Day was important for Crane as a day when nature and workers could be seen in powerful unity. Crane most beautifully expressed this in his Garland for May Day of 1895, a front page for The Clarion newspaper that we hold in our archive. A barefoot woman holds up a wreath with slogans of ‘the land for the people’ and ‘Hope in work, joy in leisure’ woven through. Crane created these souvenirs each year to celebrate May Day and in Gallery One we show two of these from 1896 and 1909, dedicated to the Workers of the World. The images show merry English men and women, celebrated through their identity as workers, in scenes of nature with maypoles, flowers and banners; a mythical past or perhaps future.

Crane’s work has memorialised a particular version of May Day, but its meanings are constantly evolving. It is day in which contradictions of ritual, spontaneity, anger and joy all mix together. Much of the discussion we hear around May Day Bank Holiday can obscure and forget the centrality of workers. But May Day is an annual monument to workers in struggle, a tiny radical dent in a system of time dominated by the pressures of work. Our collection holds varied badges, banners, posters and publications all marking May Day. Today, amidst the horrors of war, the cost of living crisis and a climate emergency, May Day offers hope in remembering those who have fought for this holiday and in re-learning our collective power as workers of the world.

Listen to Shirin discussing May Day Rituals with BBC Radio 3 Free Thinking Presenter Matthew Sweet, on BBC Radio Sounds.

Visit People’s History Museum to discover the story of unionism and in Gallery One, you can explore the harsh working conditions at the Bryant & May match factory through an interactive game. The museum and its exhibitions are free to visit with a suggested donation of £10.

Discover the stories and collections of the museum when you visit the May Day Makers Markets, which take place on Saturday 3 and Sunday 4 May. Taking place in PHM’s Grade II* listed Engine Hall the event will raise vital funds for the museum’s work as well introducing individual makers and creators to its visitors.

People’s History Museum is open every day except Tuesday, from 10.00am to 4.00pm. The archive is open Wednesday to Friday, 10.00am until 4.00pm. Booking essential.

The museum’s internationally significant collection includes items of national importance from the last 250 years of British social and political history. PHM’s archive is home to the complete holdings of the national Labour Party and Communist Party of Great Britain and over 95,000 photographs relating to the growth of democracy in Britain, covering not only parliamentary reform, extension of the vote and general elections, but grassroots organisations and campaigns also.

An earlier version of this blog was published on 1 May 2022.