On 5 July 2023, the National Health Service (NHS) celebrated its 75th birthday. Launched by Minister of Health Aneurin Bevan in 1948, the NHS aimed to bring free and reliable healthcare to all. The establishment of the NHS as a universal healthcare system was a key moment in health equality and in socialist policy. However, it is not without its difficulties.

Sarah Thompson-Cook is a Mental Health Nurse and Lecturer in Mental Health Nursing at Manchester Metropolitan University. In this blog, she explores the history of mental health services in the NHS, and the ongoing crisis recognised by organisations such as the Socialist Health Association.

This blog references historical examples of the harmful language used in institutional research and policy around mental health.

As a mental health nurse, I’ve witnessed the impact of chronic bed shortages and overstretched community services. I’ve seen quiet rooms on wards hastily turned into bedrooms and arranged transport to take patients to hospitals hundreds of miles away from their families. I have observed mental health moving away from being considered the ‘Cinderella’ service to being a minor political football, with politicians promising that mental illness will have an equal footing as physical illness. As an academic, I’ve learned that throughout history, we’ve never got it right when it comes to mental health services.

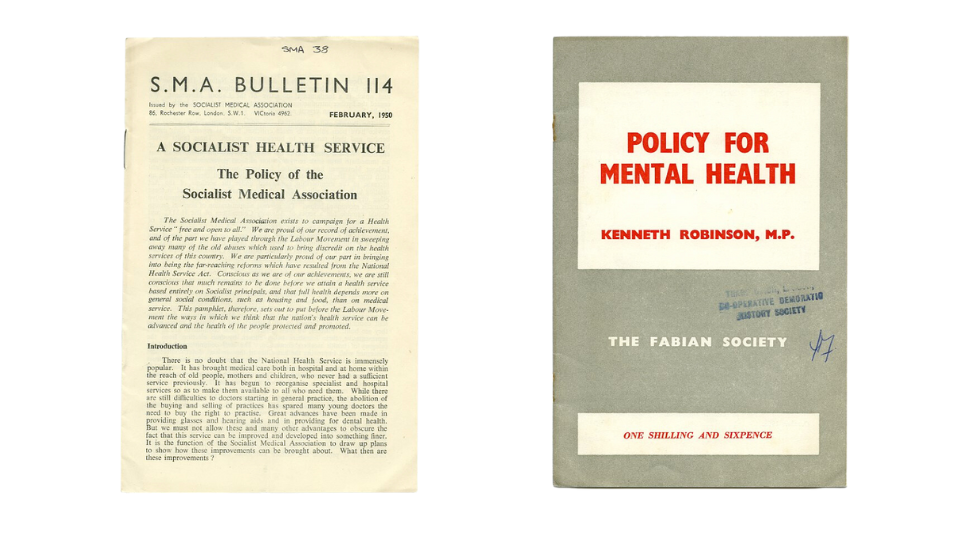

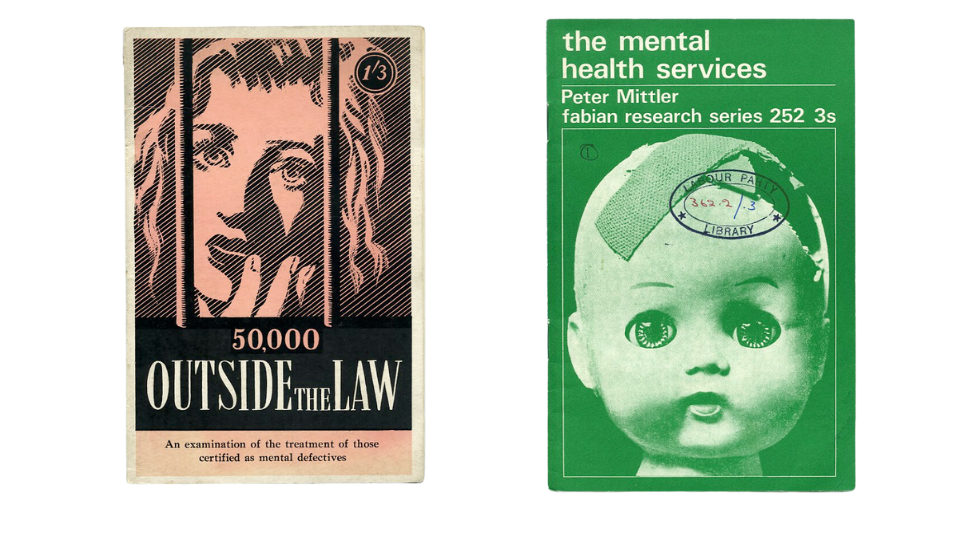

The old asylums were built at a time when the public feared the mentally ill. It was preferred to segregate them in high walled institutions, which were usually landmarked by a water tower. Until the National Health Service Act of 1947, local authorities were responsible for the funding and upkeep of the mental institutions and many simply did not want to invest money in them. These crumbling institutions, described by the Socialist Medical Association (SMA) as ‘remnants of Poor Law’, remained in place for many years. The purpose of many of these old buildings was custodial, at odds with advances in psychiatric treatment such as the antipsychotic revolution of the 1950s.

The Royal Commission on the Law Relating to Mental Illness and Mental Deficiency, otherwise known as the Percy Commission, met from 1954 to 1957 to consider reforms to mental health services. The commission recommended inpatient treatment be provided for mental health patients in district general hospitals. The Percy Commission led to the 1959 Mental Health Act which stripped the Superintendent of their authoritarian powers and embedded community treatment as policy.

In 1957, the SMA pamphlet ‘A New Deal for the Mentally Disordered’ reported that overcrowding in mental hospitals was at crisis point. Hospitals on average were over occupancy by 14.8%, with some over occupied by up to 65%, but it was argued that providing extra beds would be a very superficial solution to this growing problem. Many hospitals were described as ‘formidable, dismal’, and it was stated there was an unmet need for community treatment, prevention and ‘half-way houses’. The SMA urged that the Percy Commission’s recommendations be implemented without delay.

In 1958, Kenneth Robinson MP, writing for the Fabian Society, highlighted the ‘grim, forbidding, isolated, uncomfortable and ill equipped’ hospitals that regional hospital boards had inherited from local authorities in 1947. Some improvements were noted such as better food and recreational facilities but overcrowding and staff shortages were an issue.

Writing for the SMA in 1958, Christopher Mayhew MP described mental illness as ‘Britain’s biggest social problem’ which was ignored by the public and even the Labour Party. He reported that there were 3,000 people waiting for urgent hospital treatment, 140,000 patients in hospitals designed to hold 121,000 and not surprisingly, mental health nurses were leaving the profession in droves.

In 1961, following his famous ‘water tower’ speech, the Health Secretary Enoch Powell passed the Hospital Plan of 1962. This aimed to progress the concept of treatment in District General Hospitals, build new hospitals and properly establish community services for mental illness. However, in 1971, the SMA reported a ‘crisis in mental health services’, with only a few modern mental health units being built in district general hospitals. The press reported patients being abused in ‘squalid and dangerous’ conditions. The SMA argued that capitalism was to blame for much of the problem, with people working in mundane jobs and living in overcrowded flats, whilst being bombarded with advertisements for luxury items they couldn’t afford. The blame for the rise in ‘revolving door’ patients was firmly placed on discharging patients back to these conditions. The promise of comprehensive community services from the 1959 Mental Health Act and the 1962 Hospital Plan had been broken. Local authorities were not meeting the demand for community services and ‘half-way houses’ for service users recently discharged from hospital.

Despite the gradual fall in inpatient numbers from the 1950s, progress continued to be slow over the next few decades with a paucity of community services being set up. Large scale closures of mental hospitals began in the 1980s. It appeared that the old mental hospitals were considered so grim that the alternative had to be better, despite the development of community services being unable to keep up with the speed of their closure.

Back to the present day, it is apparent that history repeats itself. The ideal balance of community versus inpatient services still hasn’t been achieved. It remains common for service users in crisis to be sent to private mental health beds hundreds of miles away from their families. The government pledged to end this practice by April 2021. However, The Observer newspaper revealed that in February this year, 420 service users were admitted to out of area beds, an increase on the previous year. These out of area private beds may have replaced the walls of the asylum, in keeping the mentally ill far out of sight of the public in their own community, whilst lining the pockets of shareholders.

In the last two years, the Care Quality Commission have deemed some mental health inpatient facilities as ‘inadequate’ with reports of poor cleanliness and maintenance, breaches of fire standards and unsafe staffing levels. It could be argued that the crumbling institutions of the past have returned and this time, with no solution in sight.

In the 75th year of the NHS, after decades of reform, mental health services are overstretched, understaffed and far too often, inadequate. Left wing organisations such as the Socialist Health Association (formerly SMA) continue to push for change whilst mainstream political parties provide vague promises of reform that haven’t yet delivered on the frontline. History gives us the opportunity to learn from our mistakes, yet decades after the Percy Commission, here we are again, fighting for the Cinderella service of the NHS.

Sarah Thompson-Cook is a Mental Health Nurse, Lecturer in Mental Health Nursing at Manchester Metropolitan University and a PhD student at the University of Liverpool. Her PhD is entitled ‘Mental Health Service Users’ Lived Experience of Political Participation’, which aims to explore the meaning of political participation for people with a mental illness. Sarah’s other interests include making learning accessible for neurodiverse students, the LGBTQIA+ rights movement and the history of the labour movement. A chance visit to the Labour History Archive & Study Centre early on in her PhD led Sarah to the political pamphlets referred to in this blog. Sarah also has her own blog, My ADHD PhD.

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM.