We’re exploring the past, present and future of protest throughout 2019, and have compiled our own protest playlist. Here our friend, curator, DJ and co-founder of Manchester Digital Music Archive, Abigail Ward shares her highlights from Manchester’s history of rebel music.

‘Music, politics and protest are inextricably entangled. As a curator, DJ and co-founder of Manchester Digital Music Archive, I love to explore the place at which all three meet.

There are many moments in Manchester’s history when making music, dancing or simply coming together in a club have been acts of resistance, or a form of defiant visibility for oppressed communities. Often, protest songs from elsewhere have been part of these moments of disruption, but sometimes original songs were birthed here too.

Steel Pulse at the National Carnival Against the Nazis, 1978 © John Sturrock

A turning point in our city’s fight against racism and fascism occurred on 15 July 1978 at the Northern Carnival Against the Nazis held in Alexandra Park, Moss Side. Approximately 40,000 people from different communities across Britain came together to protest against the National Front and other racist groups. Manchester punk heroes Buzzcocks performed, as did Birmingham’s Steel Pulse, who shocked the crowd by playing their protest song Ku Klux Klan in full Klan regalia. Follow this link to watch a film about this momentous day.

Moss Side’s fertile black music scene of that era also gave rise to reggae band Harlem Spirit, who in 1980 released one of Manchester’s greatest protest songs, Dem A Sus, which was written about the controversial stop and search (‘sus’) laws that were being used at that time to target young black men in Hulme and Moss Side. Sus laws were cited as one the key factors in the Moss Side riots of 1981.

Around the same time Buzzcocks singer Pete Shelley released Homosapien, a song about queer male love. The song is typical of Pete’s style in that it is fizzing with excitement and cheek, but perhaps isn’t direct enough to be considered a true protest song. It did, however get banned by the BBC, allegedly for the line ‘Homosuperior in my interior’.

Undeniably influenced by Pete Shelley, Morrissey emerged in 1983 as Manchester’s new queer agitator, but it was a later paean to vegetarianism, Meat Is Murder, that became his most plain speaking protest song:

‘And the flesh you so fancifully fry,

Is not succulent, tasty or kind,

It’s death for no reason,

And death for no reason is murder’.

Words that may well have impressed William Cowherd and Joseph Brotherton, two Salford activists who were instrumental in setting up the Vegetarian Society in 1847. Another feather in radical Manchester’s cap.

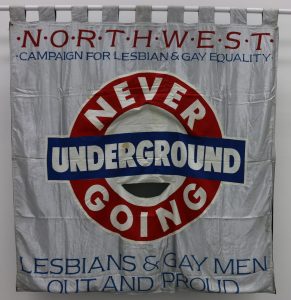

February 1988 saw one of Manchester’s biggest ever demonstrations, the Stop the Clause march, organised to oppose the enactment of Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988, which banned local authorities from ‘promoting homosexuality as a pretended family relationship’. Attended by approximately 20,000 people, the march was a pivotal moment in UK LGBT+ history and led to the explosion of queer clubbing in Manchester known as ‘Gaychester’.

At the rally in Albert Square in front of Manchester’s Town Hall, punk musician and activist Tom Robinson performed his protest anthem Glad to be Gay, altering the words to include reference to Manchester’s then Chief Constable James Anderton, a Christian zealot who had described those affected by HIV and AIDS as ‘swirling around in a cesspool of their own making’.

You can see Tom performing at the Stop the Clause march here, 12 minutes in:

As a DJ, one of my most played seven inches is Chicago / We Can Change The World by Salford songwriter and activist, Graham Nash. The lyrics of the song refer to the anti-Vietnam War demonstration that took place during the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago and the subsequent trial of the Chicago Eight. Cherished for its massive groove as much as its message, Chicago has since been sampled by numerous hip hop artists including Rascalz & KRS-One.

Nash also performed with Crosby, Stills and Young on the latter’s Ohio, which was described by The Guardian in 2010 as the ‘greatest protest song of all time’. Explicitly critical of the the US President Richard Nixon’s administration, the song concerned the Kent State shootings of 1970 in which four unarmed students were gunned down by the Ohio National Guard during a protest against the bombing of Cambodia by US military forces.

Ewan MacCcoll, another world famous Salfordian, is considered one of the most acute social commentators in English folk music. His protest songs are legion, but The Manchester Rambler from 1932 is a particular favourite, inspired by the Kinder Mass Trespass by the Young Communist League of Manchester:

‘He said “All this land is my master’s”

At that I stood shaking my head

No man has the right to own mountains

Any more than the deep ocean bed’

These tracks are just a few highlights in Manchester’s history of rebel music. But which Manchester musicians are letting their freak flag fly in 2019? Sadly, not very many prominent ones. But the underground scene is healthy.

ILL are a fierce female four-piece purveying genre-bending disobedient noise. Their track Kremlin is about Pussy Riot:

‘What’s big and red and throbbing?

The shadow of the Kremlin.

What’s tall hot and nervous?

The perverts in Congress

Shall we just sit here

Discuss the semantics

And let these baboons go on with their antics?’

Contemporaries of ILL, Cabbage burst onto the scene a few years ago with filthy hair and a good line in scattershot political rhetoric. Their 2016 track Uber Capitalist Death Trade exemplifies their lyrical approach, which is at times reminiscent of under appreciated Manchester post-punk band Big Flame.

Big Flame were a huge influence on Welsh rock dissenters Manic Street Preachers. In a 1991 interview Richey Edwards of Manic Street Preachers said, ‘The 80s, for us, was the biggest non-event ever. All we had was Big Flame. Big Flame was the most perfect band. But we couldn’t play their records ‘cos they were too avant garde.’

The Manics themselves are no strangers to a protest song. Their surprise 1998 number one hit about the Spanish Civil War (1936 – 1939), If You Tolerate This Your Children Will Be Next, was inspired by the idealism of Welsh volunteers who joined the leftwing International Brigades fighting for the Spanish Republic against Francisco Franco’s military rebels. Its stand out line ‘if I can shoot rabbits, then I can shoot fascists’ was taken from the book Miners Against Fascism by Hywel Francis.

The track is featured on PHM’s new protest playlist, along with a number of other protest songs touched upon in this piece. Dive in below!’

Part of PHM’s year long programme exploring the past, present and future of protest, marking 200 years since the Peterloo Massacre; a major event in Manchester’s history, and a defining moment for Britain’s democracy.

Part of PHM’s year long programme exploring the past, present and future of protest, marking 200 years since the Peterloo Massacre; a major event in Manchester’s history, and a defining moment for Britain’s democracy.

Abigail Ward is a curator, DJ and co-founder of Manchester Digital Music Archive.

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM.

People’s History Museum is open seven days a week from 10.00am to 5.00pm, and is free to enter with a suggested donation of £5. Radical Lates are the second Thursday each month, 10.00am until 8.00pm.