In this long read, disabled historian Jaime Starr explores the history and legacy of the Disability Discrimination Act, 30 years on from it becoming law, through objects in People’s History Museum’s (PHM) unique collection.

The Disability Discrimination Act (DDA) was signed into law on 8 November 1995. After years of campaigning and direct action protests by disabled and D/deaf activists and allies, this became the most significant piece of national legislation that addressed disability discrimination. As well as prohibiting direct discrimination – for instance, refusing to hire a disabled person who is qualified for the job – the DDA (which has since been replaced by the Equality Act 2010 everywhere except Northern Ireland) also required service providers and employers to actively prevent indirect discrimination – for instance, a hospital excluding visually impaired people from accessing written information by not providing large print letters.

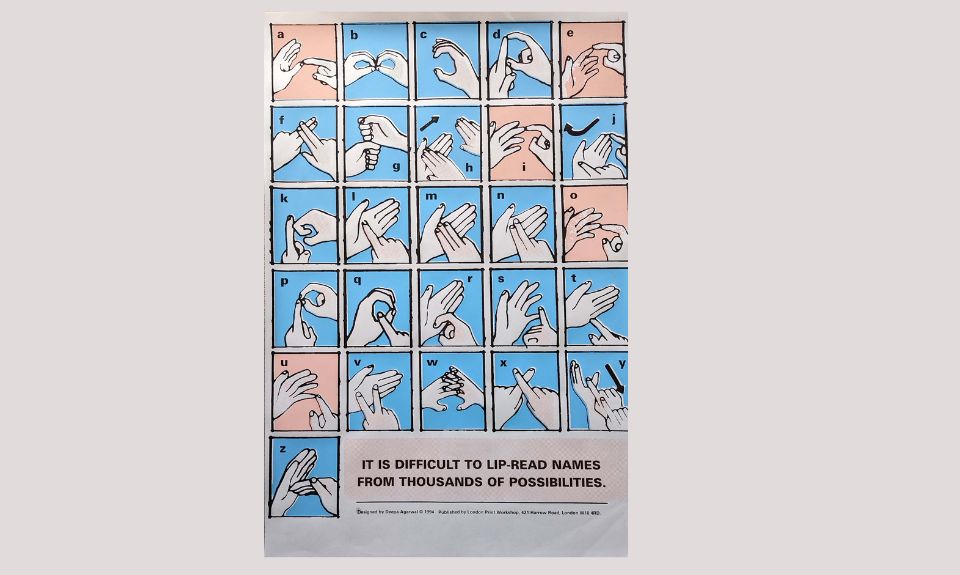

The act required that ‘reasonable adjustments’ should be made when designing public spaces and services to ensure that wherever possible, disabled people can have an equal experience to that of a non-disabled person. A service provider is expected to provide reasonable adjustments for the public even if they don’t know of any disabled customers. For example, I am a deaf person – if I go to a theatre, there should be a hearing loop, and/or captioned or BSL interpreted shows, so I can access the performance the same as my hearing friends. The theatre should expect d/Deaf visitors and provide d/Deaf access without me personally making a request.

Not providing accessible services can lead to a cycle of exclusion – a service isn’t accessible, so disabled people don’t use it, so the business owner thinks they don’t need to be accessible because no disabled people use their services.

Next time you’re outside, look at how many buildings have stairs at the entrance, or when you’re visiting the cinema, try and spot how many don’t run captioned screenings.

While the law tells businesses and service providers that they should be accessible, there is no government monitoring to ensure compliance. The DDA and Equality Act require an individual disabled person who has been discriminated against to have the time, money and energy to undertake legal action.

When disabled people do manage to undertake legal action to force businesses to follow equality law – usually after polite requests, offers of mediation, and other attempts at correcting the problem – they can experience harassment and vilification for doing so.

Discrimination and exclusion is rife. Today, only one in four train stations in the UK is wheelchair accessible, and most trains and buses are only able to carry one wheelchair user at a time, limiting our ability to travel with friends and family. Meanwhile 81% of guide dog owners have been illegally refused access to a business or service

The 87,000 Deaf BSL users in the UK consistently face exclusion in healthcare, education, and government provided services where qualified sign language interpreters are not provided. During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, Deaf BSL users took legal action against the UK government, as the daily Covid briefings – which delivered vital health information about lockdowns, symptoms of illness, and shielding – were not BSL interpreted. Subtitles are not a reasonable adjustment for BSL users, as BSL is their first language, and discrimination in education means the average reading age for a Deaf BSL user is nine.

The way the law is set up and the burden it places specifically on disabled people to call out lack of access and discrimination means progress for disabled people’s equality is slow and disabled life in the UK difficult.

Poverty is a major issue for disabled people. We face discrimination in the workplace, often struggling to find jobs as disclosing disability during the recruitment process can lead to the assumption that we won’t be capable employees, no matter how well qualified we are. Some disabled people are put at risk of losing our jobs if we lose our Access To Work (ATW) funding, which can pay for equipment or support staff to enable disabled workers to do our jobs.

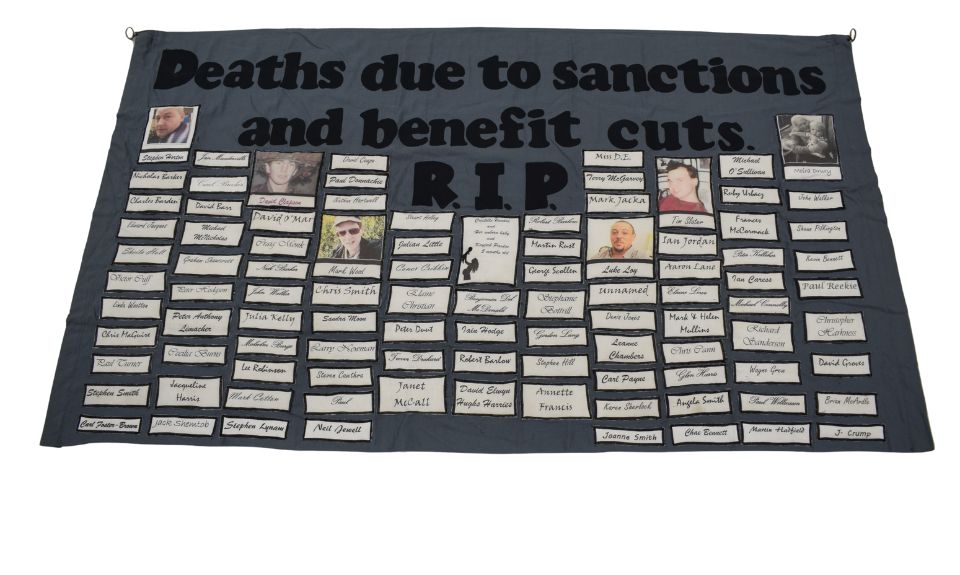

During the 2010s, the austerity economic policies led to significant financial cuts to services like the Independent Living Fund (ILF), which supported disabled people to live independently, rather than in care homes. The Conservative government at the time also launched several benefit reforms that caused fear, hardship, poverty and deaths amongst disabled people. This included the introduction of Personal Independence Payment (PIP) as a more restrictive replacement for the Disability Living Allowance (DLA), as well as replacing Incapacity Benefit with Employment Support Allowance (ESA).

Benefit reassessments, and disabled people being removed unfairly from their benefits, have been named by coroners as contributing to the deaths of thousands of disabled people, often from suicide, but in some cases from starvation following the withdrawal of care support after losing PIP, or inability to pay for life-saving medications. Between 2012-2019, austerity policies caused 334,327 excess deaths, and the UK government was censured by the United Nations (UN) for systemically violating disabled people’s rights.

Another area where disabled people are still struggling for equality is reproductive autonomy. Disabled people who become pregnant are often automatically referred to social services, as an assumption is made that they will not be competent parents, solely because they are disabled.

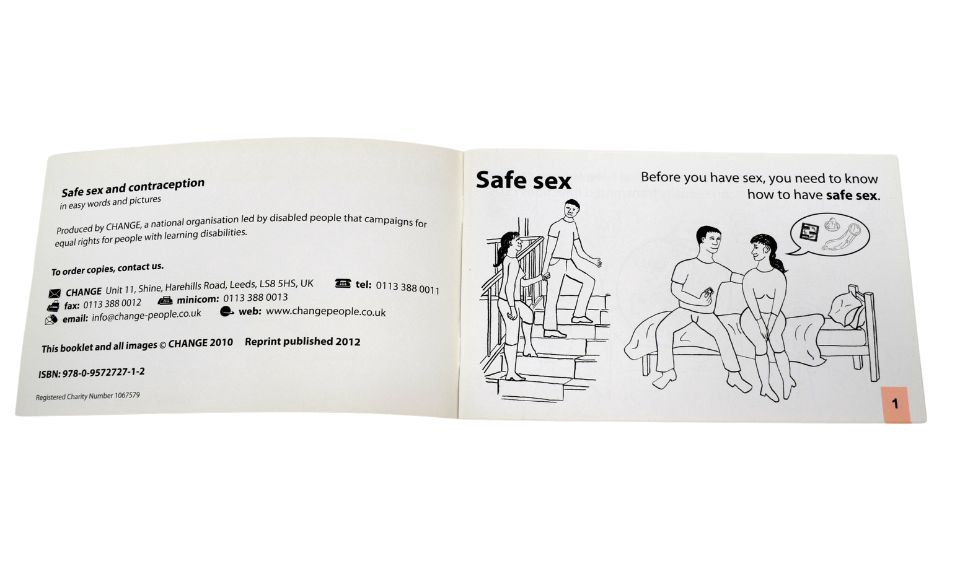

People with learning disabilities face further restrictions on their reproductive rights, with those who need care to support their lives as adults often not being supported to have romantic or sexual relationships. There are regularly cases of people with learning disabilities being referred for denial of liberty (DOL) orders through the courts to restrict their access to sex or relationships – these can include involuntary sterilisation which, while a complex issue, is viewed by some disabled activists as a eugenicist action based on societal discomfort with disabled people having sex or relationships. People with learning disabilities are often not given sex education, and are statistically at higher risk than others of abuse, which it can be argued is exacerbated by not having been taught about sex.

In 2011, the Winterbourne View care home came under investigation by undercover reporters working for the BBC’s Panorama programme. Journalists discovered that the home’s residents, primarily Autistic people and people with learning disabilities, had experienced significant neglect and abuse. Panorama’s investigation footage led to 11 members of staff being arrested and convicted of 38 counts of neglect and ill-treatment of the residents which was described by the judge as “cruel, callous and degrading” abuse. In the wake of the report, the Care Quality Commission inspected 150 hospitals and care homes. Their findings uncovered widespread poor practices in mental health units and care homes for people with learning disabilities.

Following the scandal at Winterbourne, the government promised that by 1 June 2014 all people with learning disabilities living in long-term residential units and hospitals would be supported to live in the community. This target has been repeatedly missed.

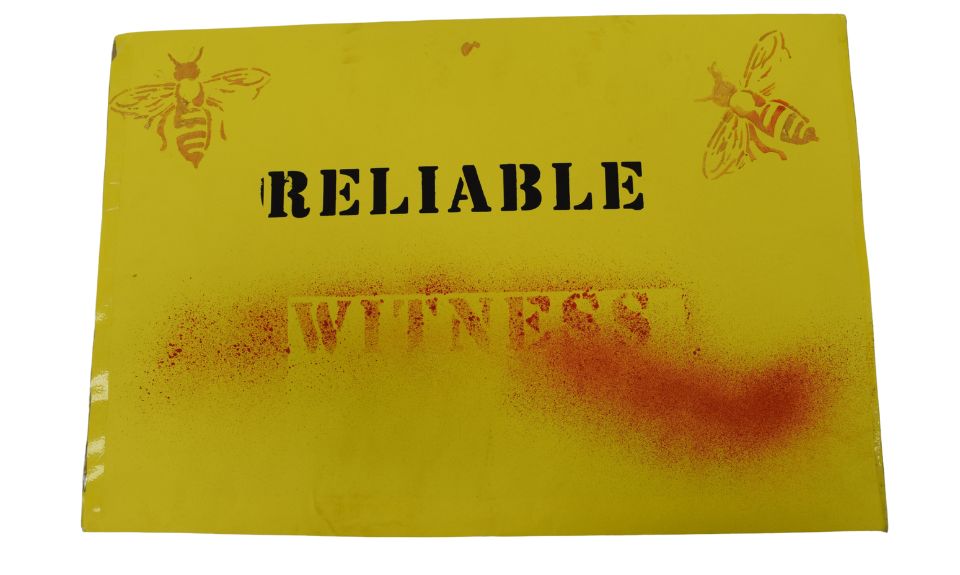

Five years after Winterbourne, in 2016, a whistle-blower at Mendip House, a care home for Autistic people run by the National Autistic Society (NAS), exposed systematic and horrifying abuse. Described as ‘Winterbourne but without the cameras’, staff at Mendip were found to have physically assaulted, poisoned, bullied and financially abused residents over a number of years.

Although the home was closed, and the staff sacked, the Care Quality Commission, an organisation responsible for regulating care homes, only fined the NAS £4,000. Meanwhile, the Crown Prosecution Service did not pursue criminal charges against staff, claiming that the ‘standard of evidence’ for a successful prosecution was not met. The Disability News Service revealed that while building the case, the police interviewed neither the whistle-blower nor Mendip residents. On 29 March 2019, Autistic campaigners protested in Manchester and London to highlight the injustices of the investigation. It is likely the ‘reliable witness’ wording on the placard challenges the perception that an Autistic person with high care needs could not be relied on to give evidence in court.

Had the government met their initial 2014 goal, it is likely that the residents of Mendip would not have experienced this abuse. As of 2024, over 2,000 Autistic people and people with learning disabilities, were still living in mental health hospitals.

Although the aim of the DDA was to address discrimination, the burden it (and its successor the Equality Act of 2010), places on disabled people to call out and legally challenge discrimination, dilutes its power and has lessened its impact. This combined with cuts to benefits, as well as questions around autonomy and perceived capacity mean that the fight for equality is ongoing 30 years later. Despite these continuing challenges, disabled people are still creating culture, and making spaces for fellowship and activism, finding and making joy in their communities. We still want rights, not charity, and disabled activist organisations today move in the legacy of our forebearers who got us this far through their protests. When I limp onto a bus with my walking stick and sit in the disabled priority seats, or have a transcribed phone call with my GP using the Relay text to speech app, or saw my colleagues at People’s History Museum excitedly discussing the Access To Work funded Deaf Awareness training they all took so I’d be better included in the workplace, I think of the disabled activists in the 80s and 90s who made all of that possible for me, and people like me. The ones who chained themselves to inaccessible buses and trains, who stormed television studios during telethons to protest society viewing us as objects of pity, who petitioned MPs and government ministers to demand we have the right to equal and equitable access to society. I think of how that activism has benefitted me, and I look for ways to get involved to make sure I’m doing all I can to ensure other D/deaf, disabled and neurodivergent people get the same kind of chances. And until things are truly equal, we’ll still be carving out spaces for disabled joy, grief, rage and pride – including in museums.

Author profile:

Jaime Starr is a former Collections Assistant at People’s History Museum (PHM) and is currently an LGBTQIA+ and disabled heritage consultant, and postgraduate researcher at Newcastle University mapping the LGBTQIA+ archives of the North East.

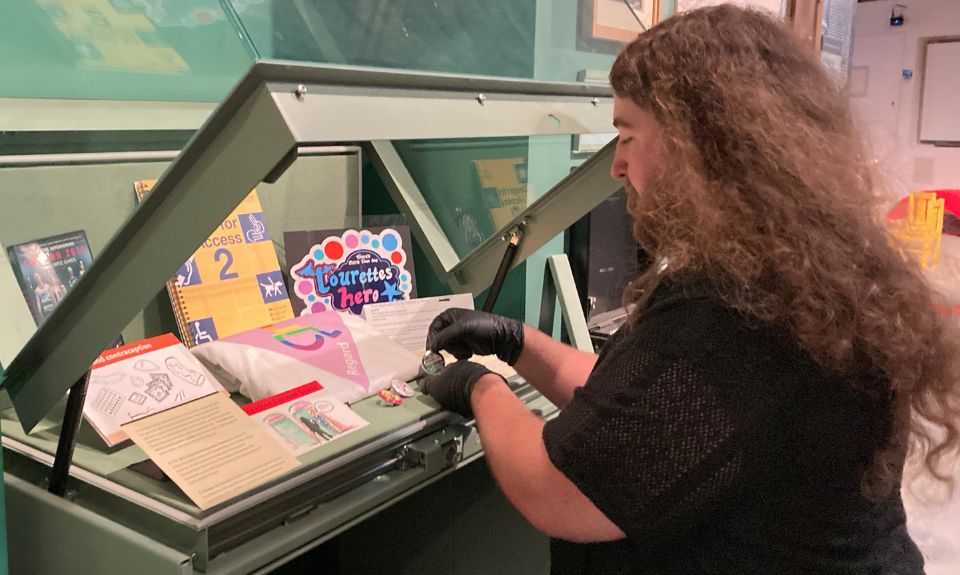

Visit PHM to see the Spotlight Collection case on Gallery One. It brings together a series of objects curated by Jaime to highlight the campaigns fought by disabled activist since the passing of the DDA in 2019. On display until 30 March 2026.

Tour virtually PHM’s 2022-2023 exhibition Nothing About Us Without Us, which explored the history of disabled people’s activism.

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM. Images supplied by contributor.