Steven Fielding, Professor of Political History at the University of Nottingham discusses the five highlights he chose from the People’s History Museum’s collection for a series of new films.

‘The People’s History Museum’s (PHM) collections and exhibitions allow visitors to explore Britain’s often dramatic and always controversial democratic history.

PHM is highlighting five objects from the museum’s unique collection in a series of films, with assistance from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the University of Nottingham. In these films I explain the objects’ relevance to our own times, and for those who want to take their journey into the past a bit further, link them to the national Labour Party archive; the complete holdings of which are housed at the museum.

When deciding which items to talk about, my task was incredibly difficult, given the huge choice on display in the museum’s two main galleries. There is certainly scope for more films, but this is what I came up with!

Housing is one of the most pressing issues in Britain today so it seemed obvious to talk about two Labour and Conservative Party posters taken from the 1950 and 1951 general elections which addressed this issue. Britain already had a housing crisis before 1939 but it was made worse due to the bombing of many of its cities during World War II. Inspired by the belief that returning soldiers, war workers and their families deserved a better life, despite huge shortages of labour and materials, the Labour government elected in 1945 built one million homes. But more were still required, which is why the Conservative Party promised to build 300,000 homes a year, a pledge they lived up to when elected to office in 1951.

Both parties used their time in government to address Britain’s housing problem. With the country facing a similar crisis today however neither the Conservative government nor the Labour Party have embraced the methods required to properly solve it. Perhaps they need to look back to their own histories to see how it might be done?

Britain is more accepting of multiculturalism than ever it was; however, some think hostility to immigration lay behind much of the 2016 vote to leave the European Union (EU). To highlight this issue, I chose a poster produced by the Labour Party Young Socialists in 1974. The poster publicised a demonstration the party’s youth wing organised to oppose growing racist hostility to non-white Commonwealth immigrants and their offspring. The event took place in Bradford and was the first rally officially sanctioned by the national Labour Party to oppose racism which was at the time being stoked up by the fascist National Front party. The 1960s Labour government had looked two ways on the issue; introducing laws to outlaw discrimination, but imposing controls designed to reduce only non-white immigration. As this poster indicates however, in the face of rising support for far right groups, Labour assumed a more assertive anti-racist stance to actively change attitudes.

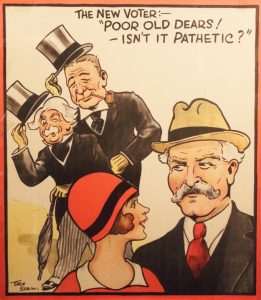

Women are still underrepresented in Britain’s political system. While there have been two female Prime Ministers since 1979, two-thirds of MPs elected in 2017 were men. Misogynistic attitudes in the Palace of Westminster are also exposed by the media on a regular basis. Things may have improved, but there clearly remains much work to do. The first election in which all women could vote was 1929, which is why I picked a poster the Labour Party produced for that contest. Women over 30 were given the right to vote in 1918 along with all men over 21. But those in their 20s had to wait; they were deemed too frivolous to vote. This Labour Party poster was meant to appeal to these first time voters but it is a paradoxically sexist pitch. It bizarrely shows the Liberal Party leader David Lloyd George and Conservative Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin as two aged suitors giving the eye to a young woman and presents the Labour Party’s Ramsay MacDonald as her more appropriate consort even though, like the others, he was in his 60s!

We live in an era of fake news, when some believe our opinions are shaped by a social media corrupted by foreign powers and a mainstream media controlled by powerful interests. However, the way we see our political leaders has always been mediated, and potentially distorted. I was therefore keen to talk about one of the museum’s most striking exhibits – the coat worn by the Labour Party leader Michael Foot at the National Service of Remembrance, held at The Cenotaph in Whitehall, London, on Remembrance Sunday, 1981. This coat was depicted in the press as a donkey jacket, which is something a manual worker might wear. As a result, it was widely believed that Foot, whose party then supported unilateral nuclear disarmament, had disrespected those who had sacrificed their lives in defence of the nation. He was, the argument went, consequently unfit to become Prime Minister. Yet, if you see the coat in the museum it is perfectly respectable and indeed Foot was praised by the Queen Mother for his choice. But, as Foot’s private papers held in the museum archive show, he received many letters from those who believed he had worn a donkey jacket.

Thanks to Brexit the language of patriotism now shapes much of our political discourse. Supporters of Leave sometimes cast advocates of Remain as traitors willing to bend the knee to Brussels, whereas Remain partisans claim that they are the true patriots as staying in the EU is in the national interest. To highlight the persistence of patriotism I chose a Conservative Party poster produced in time for the 1924 general election.

To 1920s conservatives, patriotism meant keeping the country’s established institutions safe from communism, which was being established pretty violently in Russia after the 1917 revolution. As a socialist organisation the Labour Party shared ends similar to the communists – a more equal society – but was, unlike them, committed to achieving change through democratic means. Some conservatives genuinely saw no difference between the Labour Party and the regime in Moscow. Others were more perceptive but still cynically claimed the Labour Party was in favour of bloody revolution. So, the poster asked voters to choose between two stark alternatives, the Union Jack or the Red Flag. Given the terrible stories coming out of Russia at the time, it was a powerful form of propaganda that arguably helped the Conservative Party end the first Labour government by winning the 1924 general election.

Britain’s democratic history is an unfinished story. It is one in which we can all play a part. These films show that looking at that history can help us better understand the present. If they demonstrate how far we have come, they also show how far we have yet to go.’

See all five films on PHM’s YouTube channel.

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM.

People’s History Museum is open seven days a week from 10.00am to 5.00pm, Radical Lates are on the second Thursday each month, open until 8.00pm. The museum is free to enter with a suggested donation of £5. Find out about visiting the museum, and check out what’s on.