The National Minimum Wage (NMW) was first introduced on 1 April 1999, the rate was £3.60 per hour (£3 for 18 to 21 year olds).

Here Darren Treadwell, Archive Officer at PHM shares memories from his first job in 1981.

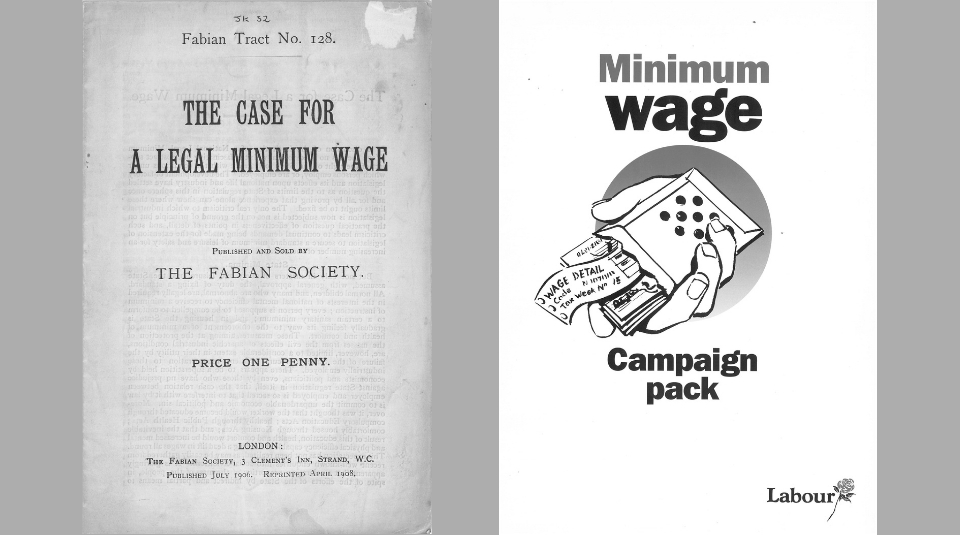

‘There are 90 years between the publication of these two pamphlets, the Fabian Tract was published in July 1906, the New Labour Minimum Wage Campaign pack was published in mid-1996. Famously Harold Wilson said at the 1962 Labour Party Conference that, ‘the Labour Party is a moral crusade or it is nothing’. That being the case the moral crusade for the minimum wage has to be the most glacial campaign of the 20th century, if for no other reason than the fact that it lasted for the 20th century!

As somebody who is a proud member of an educational elite, that 1% of the population who leave school with not a single qualification to their name, 1981 was a crap year to be 16.

The year gets remembered, by and large, for two things, riots and a wedding. Starting in April and carrying on until early July various cities erupted into violence; Liverpool, Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds and London all fought for top spot on the news each night, or so it seemed. Then it just stopped, seriously, just stopped. There was a wedding on telly. Wednesday 29 July, the heir to the throne, Prince Charles, got married. Some people had the day off work, 2.5 million people didn’t have a job so we were not asked. We just stayed at home.

Political vocabulary is constantly evolving, and it is not a retrospective re-write on my part but I did notice it at the time. Certain phrases kept cropping up in TV interviews and in the printed press, ‘inward investment’, ‘flexible economy’, ‘deregulation’. Translated they mean, selling companies to the highest foreign bidder, making it easier to sack people, and getting rid of nationalised stuff. My personal favourite was ‘rationalisation’, the outcome of which was some poor sod working longer hours for less money. As I did in my first job, stacking wood in a factory, not a job, more of a task. From 8.00am to 4.30pm Monday to Friday I stood behind a saw machine with five blades on it, imaginatively called a Five Cutter, and as somebody fed in the planks of wood from the front, they were cut into strips and I took them off the back and stacked them on a wooden palate. And that was it, all day every day.

The wood was from South East Asia and called Keruing, it was usually damp and stank, the factory as whole was hot and damp at the same time, the noise was so bad from the various machines that we had to wear ear protectors. There was an ever present fine wood dust in the air, as well as the constant need to dodge flying chips of wood that came off the back of band saws that were lined up about 15 feet away from me.

For this dear reader I was paid £1 per hour, yep, one of your English pounds per hour. I took home £39 per week, I made so little that I didn’t actually pay tax, and when Margaret Thatcher’s Chancellor of the Exchequer feels sorry for you it’s fair to say your wage level is not good. If I worked a Saturday morning my wages rocketed to £44 per week. Oh and I lived two miles from the factory, there were no buses, all ‘deregulated’ so I walked there and back each day.

On 12 April 2018 I attended a memorial service at Westminster Central Hall, it was for Rodney Bickerstaffe, former Trustee of People’s History Museum, founder of UNISON trade union, and along with the Birmingham MP Clare Short, one of the main architects of the National Minimum Wage Act of 1998. It is perhaps not right to leave a memorial service in an angry mood but somehow I managed it.

I couldn’t help thinking of all the pointless and unnecessary deaths of young people there had been in the years prior to the minimum wage. I found myself thinking of a particularly revolting government scheme, introduced in 1978 by the Labour government of James Callaghan, but taken up with a telling enthusiasm by the government of Margaret Thatcher, called the Youth Opportunities Programme (YOP) and how lucky I was not to have been on one. If you were between 16 and 18 years old you worked in exactly the sort of job I was doing and the government paid the wages, all £23.50 of it, yep there were people earning less than me! You did it for a year on the vague promise, very vague, that there would be a full time job for you at the end of it. Of course they very often failed to materialise. But between 1978 and 1982 24 young people, mainly boys all under 18, were killed on YOP schemes, on building sites, or factories doing exactly the sort of job I was doing.

I got involved in something called The Youth Trade Union Rights Campaign and since then, well, I have never really looked forward!

Anyway I am going to stop writing now as a Deliveroo person on a bike is brining me my tea. So glad we live in a gig economy and not a ‘flexible’ one where people are worked to the bone for low wages!

Moral crusade anyone!’

Darren Treadwell is part of PHM’s expert Archive Team helping researchers discover our incredible collection of political archive material.

The museum’s internationally significant collection includes items of national importance from the last 250 years of British social and political history. It is home to the complete holdings of the national Labour Party and Communist Party of Great Britain and over 95,000 photographs relating to the growth of democracy in Britain, covering not only parliamentary reform, extension of the vote and general elections, but grassroots organisations and campaigns also.

The archive is open Wednesday to Friday, 10.00am to 4.00pm, lunchtime closure 12.30pm – 1.30pm.

Please make an appointment prior to your visit by emailing archive@phm.org.uk or telephoning 0161 838 9190.