The ambulance workers are on strike. The Health Secretary says that he is calling in the army because the unions ‘are still insisting on 11.4%…and they are prepared to take industrial action in support of that.’ It is winter and ambulance workers huddle around braziers as they demand a real pay rise.

This was the scene of the ambulance workers’ dispute, 1989-1990. In September 1989, 19,000 ambulance workers started an overtime ban and, after no movement from the Government, crews began to refuse non-emergency calls. They received huge popular support. In January 1990 there was a 15 minute stoppage of work across the country in support of ambulance workers (see photograph of the Manchester rally). This included our own archive officer Darren Treadwell, who led a walk out from the Birmingham factory where he then worked, alongside Cadbury workers and Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. Finally in February 1990 a deal was reached between the unions and the Department of Health with a pay rise of 16.9% agreed over two years. Roger Poole, the chief negotiator for the unions, claimed a massive victory, driving ‘coach and horses through the Thatcher government’s pay policy’. For rank and file ambulance workers there was still much to be desired in the deal, but four years after the defeat of the miners’ strike (1984-1985), it did signal a tide had turned against the Conservative government.

Fast forward over thirty years and ambulance workers are on strike again. Clare Winter, an ambulance worker at the time, shares her memories with PHM Researcher Dr Shirin Hirsch.

I joined the service in 1987 and did my paramedic training in 1989. The feminist in me wanted to work in a profession that was male dominated. It was important to show women could do the physical work like lifting and carrying patients and driving fast on blue lights. When I joined women were only accepted on the men’s terms and it was quite a challenge. At some stations I was the only woman and some of my colleagues made life difficult. Working one to one was usually fine, but collectively the male pack mentality was often hard to deal with. Porn/pin ups were still common on some station walls. This was a hard fight, especially in one particular station that the union convenor was attached to. As more women came into the job it became easier to deal with and by the time I left the stations in my area had removed all those images. Thinking back now I don’t know why we didn’t take it up as a union issue. But I liked the camaraderie, the gallows humour and the fact that you were helping people in very difficult circumstances.

I have a very hazy memory of the beginning, but we were very angry that the union bureaucracy kept trying to put a dampener on us going out on strike and always called it a dispute not a strike. Most workers were in a union and wanted professional recognition and wage parity with the fire brigade. The paramedics also wanted a pay increase in recognition of their skills. There were a number of militant stations, Camden was one, which gave us confidence to keep pushing to go out on strike. Ken Clarke, the Health Minister, called us ‘glorified taxi drivers’ which just showed the Tory distain for health workers at that time.

Being out on strike was fantastic. After the defeat of the miners’ strike worker confidence was really low, but we knew we were doing the right thing because we had so much support from other workers and the public. At the start of the strike I was absolutely terrified of going around workplaces and speaking. By the end I loved it. Just shows how confidence grows in the struggle and all the support we had.

I remember when the Government brought in the army to cover. The conflict was still going on in Northern Ireland and it really felt horrific to have troops on our streets.

My area stations Hackney, Dalston, Shoreditch and Canonbury had people on collection duty, going to workplace meetings and people on standby to go out on calls. We pooled our daily collections and paid ourselves a weekly wage. When Shoreditch pulled out of this it caused a lot of anger.

I remember a feeling of disappointment at the deal we got, but that it was the best we could get. People were also struggling to manage on strike pay and collection money. Most married workers were dependent on overtime both before and after the strike to get by on their wages. Various rota changes and new technology were introduced after the strike that made working conditions more difficult, like going out on standby, waiting for calls rather than staying on station.

I stayed in the service for another 10 years, but had to leave after a number of back injuries. There was still a lot of heavy lifting during that time. Better lifting equipment was being introduced by this time, but the damage was already done. Also I hated the 12 hour shifts.

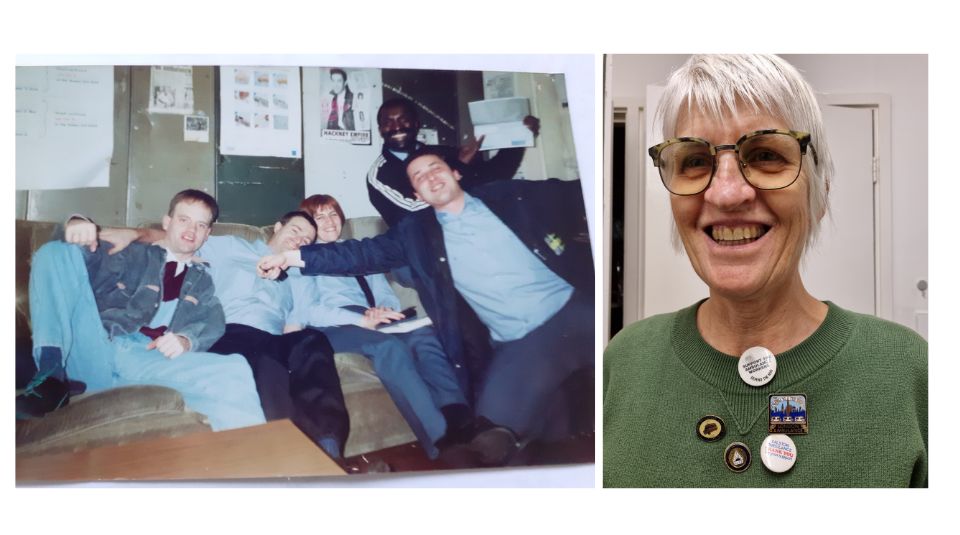

This photo is of my colleagues and me in Dalston Station. Wally, my crew mate, is holding up his paltry pay cheque which we’re all laughing about. I have happy memories of working there.

Dalston Station bought equipment to make badges and those on station duty would make them for us to take out on collection duty. Here I am over 31 years later with some of the badges I’ve kept from this time.

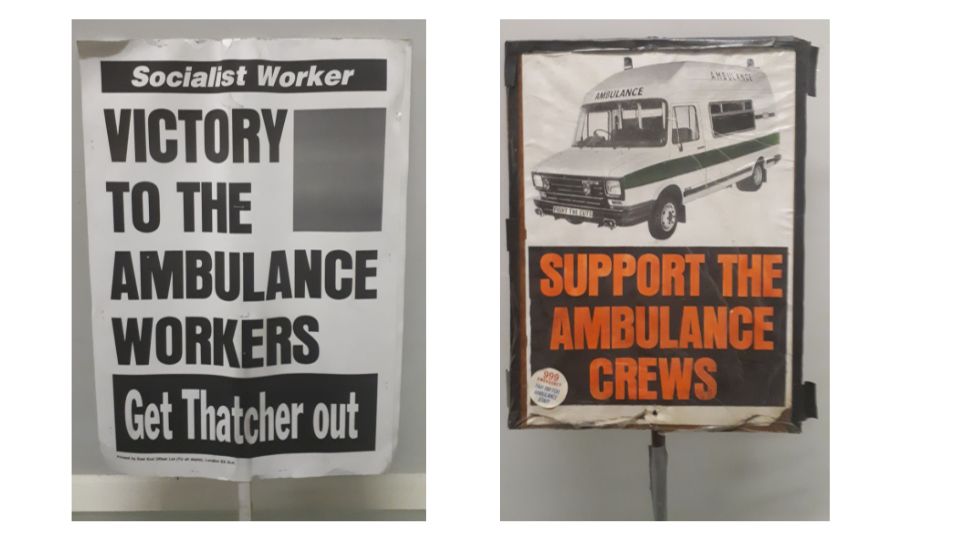

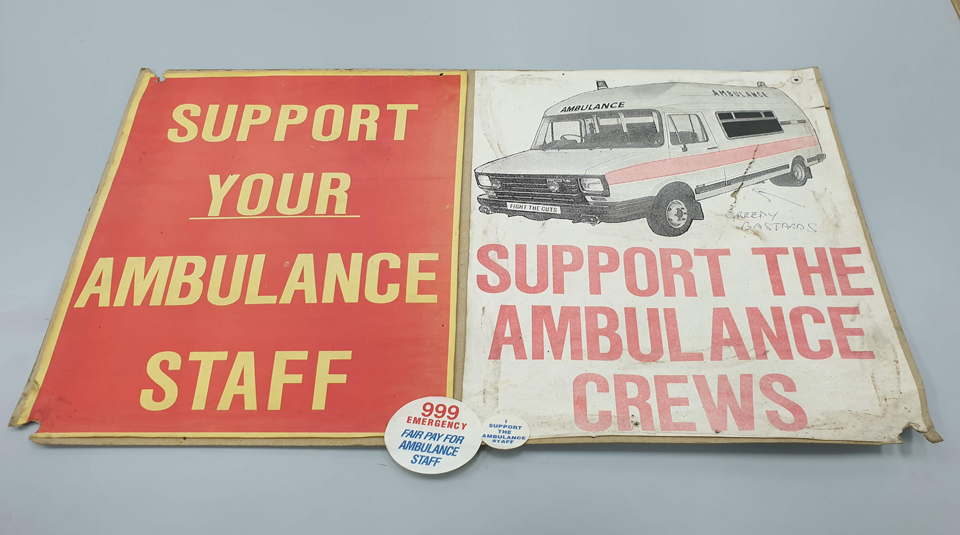

On display in Main Gallery Two are two posters from the Deansgate Ambulance Station, Manchester with the slogans ‘Support your ambulance staff’ and ‘Support the ambulance crews’. In the wider collection but not currently on display People’s History Museum have ambulance strike placards, stickers, badges and collection buckets. Collection duty was always a positive experience. We would often go to the same street corners and markets daily or weekly and people were so generous with what they gave us. There was a lady who gave us £1 each week. People always came up to us to show us their support. We knew it was an important fight and that we had public support.

I think that support across the workplaces and with other workers was so important in our strike and helps you keep going. Solidarity with your strike today!

Clare Winter is a former NHS ambulance worker .

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM. Photographs supplied by contributor.

In the galleries at People’s History Museum you can learn more about the ambulance workers and their struggles for fair pay, as well as other disputes and protests that shaped this period.

People’s History Museum is open every day except Tuesdays, 23 December, Christmas Eve, Christmas Day, Boxing Day, New Year’s Day & 2 January from 10.00am to 5.00pm. The museum and its exhibitions are free to visit and most visitors donate £10. To find out about visiting the museum, its full exhibition and events programme visit phm.org.uk.