The theme of South Asian Heritage Month 2022 (SAHM) was ‘Journeys of Empire’. In 2022, SAHM coincided with the 75th anniversary of the partition of India. PHM’s Collections Assistant Shivaya Prasad explores protests, campaigns and movements amongst the South Asian diaspora, through our archive and collection.

South Asian Heritage Month (SAHM) seeks to celebrate and remember South Asian history, culture, and community. In 2022, it coincided with the 75th anniversary of the Independence of India, partition, and the creation of Pakistan in 1947. The partition of India and Pakistan caused the mass migration of millions of South Asians, made up of Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs, sparking brutal violence and civil war across South Asia. Its impact is felt by the global South Asian diaspora and is a hugely significant time period. In 1947, East Bengal was also part of Pakistan; Bangladesh became independent in 1971 after the Bangladesh Liberation War. This blog explores SAHM’s 2022 theme, ‘Journeys of Empire’, through People’s History Museum’s (PHM) archive and collection. The content will cover anti-imperialist, anti-racist and working class solidarity protests, campaigns, and movements amongst the South Asian diaspora. The material discussed sheds light on the nuanced struggle, activism, and complexities of the 1947 partition and the consequential impact on South Asian people and their heritage.

Here is an image of the India League banner from around 1930. The India League was a British based campaigning organisation led by Vengali Krishnan Krishna Menon, or V. K. Krishna Menon, a communist radical who campaigned for Indian independence. Menon migrated to London in 1924 and joined the Commonwealth for India League in 1928. He radicalised the organisation and transformed it into the India League, which campaigned for full independence and self-governance. The India League banner was last on display in PHM’s 2020-2021 banner exhibition.

The fight for Indian independence was ongoing; Sathnam Sanghera articulates this in ‘Empireland.’ He states, ‘When the British Empire was at its territorial peak in the early 1920s, it covered 13.71 million square miles which represents 24% of the earth’s land area or equivalent to 94% of the moon’s surface area.’ It is estimated that the British Raj was responsible for the deaths of 35 million Indians.

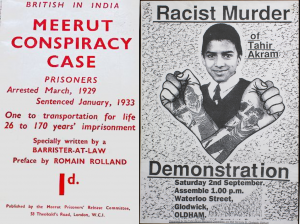

While these protests were happening in the UK, anti-imperial movements and anti-colonial sentiment were prominent in India. The treatment of Indian workers under the British Empire was very poor, as is evident in the Meerut Conspiracy case. The PHM archive holds the Meerut Prisoners Release Committee Transcript. From 1928 to 1929 there were many strikes and industrial disputes because of the poor working conditions and safety measures in the railways, which were controlled by the British Raj. The British colonial government arrested those protesting, including Indian trade unionists and socialists. All the accused were connected by working class political activity; the British were concerned about the spread of communist and socialist ideas. The prisoners were tried at Meerut and did not have access to a jury. The trial gained attention in England, and inspired the 1932 play ‘Meerut’, performed by a Manchester street theatre group. The struggle for independence and freedom for South Asian people are not isolated incidents, but part of the greater collective struggle against colonialism and capitalism.

India achieved independence on 15 August 1947. This was a huge achievement, albeit complex and led to further violence at the fault of the British imperial government. Shashi Tharoor details how the partition of India into India and Pakistan was one of the ‘biggest accomplishments of British imperialism’, using their ‘divide and rule policy’. More than a million people died during partition and 17 million were displaced. Initially, Britain did not want to give up their colonies, but the lack of funds post World War II and growing anti-imperialist sentiments led to India’s division. Cyril Radcliffe, a commander of the Order of the British Empire, was assigned responsibility of India’s division and the creation of new borders, despite having never visited India prior. The maps were rushed, drawn up in weeks, and India was left in civil war and ruin. The line which divided India and Pakistan was called the ‘Radcliffe line.’

Partition led to war, civil unrest, and poverty. After partition, there was a subsequent mass migration of South Asian people to the UK. Other reasons for the large South Asian migration to Britain throughout the 20th century are the British Nationality Act 1948, and the migration of Indians from Uganda and Kenya to Britain. Sanghera states ‘Britain is multicultural because its Empire was.’ He quotes Sri Lankan activist Ambalavaner Sivanandan who said, ‘we are here because you were there’ which effectively encapsulates the theme of ‘Journeys of Empire.’

‘Journeys of Empire’ are documented throughout PHM’s collection, which includes examples of South Asian activism, heritage, community and presence in the UK. The Racist Murder of Tahir Akram poster (1989) calls for a demonstration in Oldham for Tahir Akram, a 14-year-old schoolboy who was shot by a group of white people who were taking random shots at people in a predominantly Asian neighbourhood; protests ensued.

This Bangladeshi Youth Front poster produced in the 1970s shows information and advice available for the local community, offering the Spitalfields centre as a place where people could meet. Some of the services offered were rent and immigration advice. The Spitalfields centre is in Brick Lane, an area with a large Bangladeshi population, which is currently undergoing masses of gentrification. The East End and Brick Lane have a rich history of social and political activism. In 1978 a young Bangladeshi man Altab Ali was murdered in London’s East End in a racially motivated attack. His murder sparked national outrage, protests and grassroots activism against racism and white supremacy.

Racist hostility towards Black and Asian people during the 1970s was partly due to the rise of the National Front and far-right Nazism. These white supremacist, separatist beliefs permeated society. There were high levels of youth and student led activism in the 1970s and 1980s, such as the Bangladeshi Youth Front, School Kids against Nazis (SKAN), and other anti-racist Black and Asian youth movements.

This small poster reads “Pakistani Student Movement DISCO.” Other contextual information about this poster is unknown, but the image itself is significant. Within an atmosphere of racial violence and unjust brutalisation of marginalised communities, there were also activist spaces cultivated to enjoy music, dance, solidarity and joy. The Institute of Race Relations discusses Asian youth movements in the 1970s, and how they fostered community and built internationalist solidarity. Some of these internationalist connections include other anti-colonial struggles, Black Power movements, the Black consciousness movement, Palestinian rights, and support for Irish self-determination.

This blog covers a small amount of history within the huge scope of ‘Journeys of Empire’ and South Asian heritage. Nonetheless, hopefully this brief overview of PHM’s collection highlights the journeys of South Asian people, from independence, partition, the creation of East and West Pakistan and migrating to Britain. These stories demonstrate the power of activism, protest and collective solidarity against British imperialism and state violence.

Find out more about South Asian Heritage Month.

Read about the South Asian women, led by Jayaben Desai, who organised the Grunwick Strike in 1977.

Teach about migration with a learning resource and book a self guided visit for your learning group to explore further.