People’s History Museum (PHM) has been in conversation with historian Dr Greig Campbell about the 1981 People’s March for Jobs from Liverpool to London. The 1981 march has been remembered through a new exhibition, So We Marched, at Liverpool Central Library until 15 June 2024. The exhibition was produced by a team of volunteer researchers who recorded 30 marchers’ oral histories. Significant research for the Giz a Job project took place in PHM’s archive.

In this long read Q&A Greig shares historic photographs and oral testimonies of those involved with the march to explore its origins, impact, and legacy in the fight for workers’ rights.

When the march was called in late 1980, the Thatcher government’s dogmatic form of monetarism and advocation of ‘self-help’ had led to a rapid decline of traditional manufacturing sectors. This surged national unemployment to an unprecedented 2.5 million, devastating working class communities.

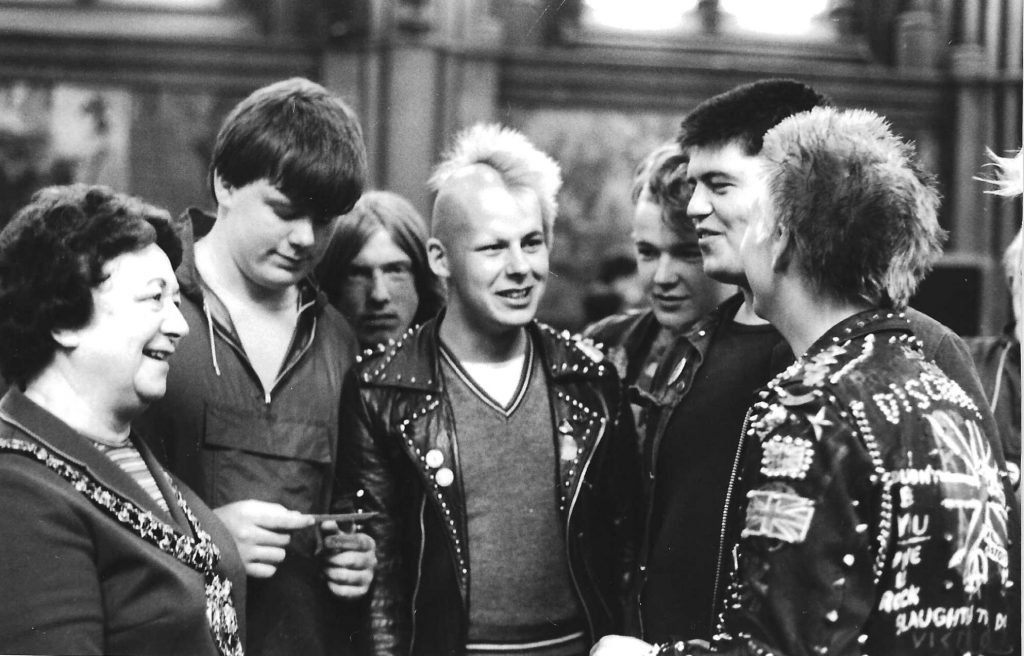

Young people across the country were badly hit, with a third of under 25s out of work. Under the infamous Youth Opportunities Programme, 16 to 19 year olds were forced into unsuitable and sometimes dangerous jobs for little pay. ‘There was nothing in Liverpool back then. Nothing. […] Highest unemployment rates in the country. There was no hope. It was desperate. They’d taken away the opportunity for young people to progress’ – Keith Mullin.

Following Thatcher’s electoral victory, rank and file trade unionists sought to make mass unemployment a key campaigning issue.

After successful anti-unemployment rallies in Liverpool and Glasgow, the concept of the 1981 March for Jobs was born; a 30 day procession through the industrial heartlands evoking the spirit of the 1930s Hunger Marches, which went from Jarrow to London. ‘MARCH FOR JOBS! MARCH WITH DIGNITY! MARCH FOR BRITAIN!’ was the march slogan.

However, this passivity irked many of the more militant participants: ‘We were demanding jobs, we weren’t begging for jobs, and I think sometimes that got lost.’ – Peter Cashman.

The principal organisers, the ‘Three Musketeers’, were Trade Union Congress (TUC) Regional Secretaries Peter Carter, Colin Barnett, and Jack Dromey. They headed up an official National Organising Committee that oversaw the identity and overall strategy.

However, the real work was undertaken by local trade unionists and activists. Local Organising Committees organised food and drink, accommodation, security, and even entertainment for the approximately 500 marchers.

The march went to London ultimately to draw wider attention to the campaign and place pressure on the government.

‘We were at the seat of power… that’s where the politicians are and that’s where the decisionmakers are.’ – Bob Towers.

Upon arriving in London, the marchers were hosted by Greater London Council (GCL) leader Ken Livingstone in County Hall. Events held in the marchers’ honour included a 150,000 strong rally in Hyde Park and Trafalgar Square, which was at the time, one of the largest political demonstrations in British postwar history.

We have found no documentary record of the exact number in the many archives we visited. We estimate approximately 500 permanent members of the so called ‘Green Army’ (280 on the western leg and 220 on the eastern leg). This number sometimes swelled with supporters.

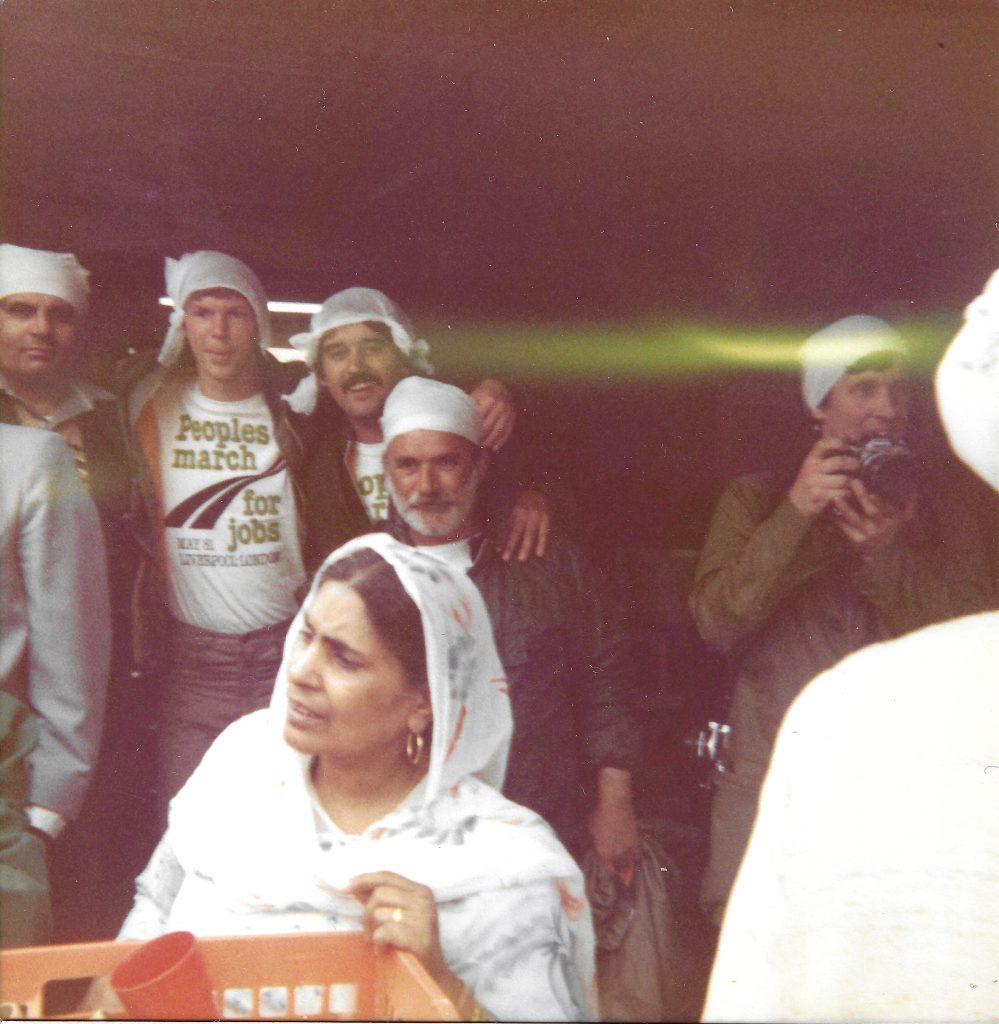

Marchers came from all walks of life; reflecting the impact unemployment had had on the people of Britian – trade unionists, leftwing activists, and campaign groups participated, including the War on Want, the Indian Workers Association, and the Spare Rib Collective. The marchers were all ages and included counterculture identities like punks and skinheads.

Sam Makin, a skilled shopfitter, and wheelchair user marched to draw attention to disproportionate unemployment affecting disabled people.

‘I had a hell of a time getting a job even before all this unemployment. What chance have I got now when there are 2.5 million able-bodied people out of work?’ – Sam Makin, speaking to the press in 1981.

The TUC and Parliamentary Labour Party were principal sponsors of the march, and the likes of Tony Benn, Dennis Skinner, Len Murray, Ken Livingstone, and Arthur Scargill spoke at solidarity rallies and in London. However, it was rank and file members, rather than bureaucrats, who played an integral role in the success of the protest.

From the outset, march organisers adopted an openly reformist agenda that sought to place pressure on the Thatcher government to change its approach. To achieve this, they recruited a broad coalition of stakeholders that included the Church and even business leaders from the Confederation of British Industry (CBI). This caused resentment amongst some of the marchers and their supporters.

The march took place against a backdrop of heightened racial tensions in Britain, with the New Cross fire and Brixton riots occurring only weeks before. Under Thatcher, Black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) were 2.5 times more likely to be unemployed than white people. The Indian Workers Association, and Black activists such as Stuart Hall and Darcus Howe, all offered their backing. There were, however, few BAME people in the Green Army.

South African human rights activist and Anti-Nazi League campaigner Peter Pillay was one. He would later play a role in the British Anti-Apartheid Movement. Others included Moss Side boxer Phil Martin, a member of the Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP). WRP members provided march security; partly in response to the threat of far right attacks on marchers. In the Black Country, Coventry and Southall, the marchers were hosted by the Sikh community in Gurdwaras. This brought great pride to Peter Pillay: ‘I know the Asian community […] welcomed us, fed us. They really treated us like their children […] This stuck in my mind – the contribution of the Asian community to the People’s March for Jobs.’ – Peter Pillay.

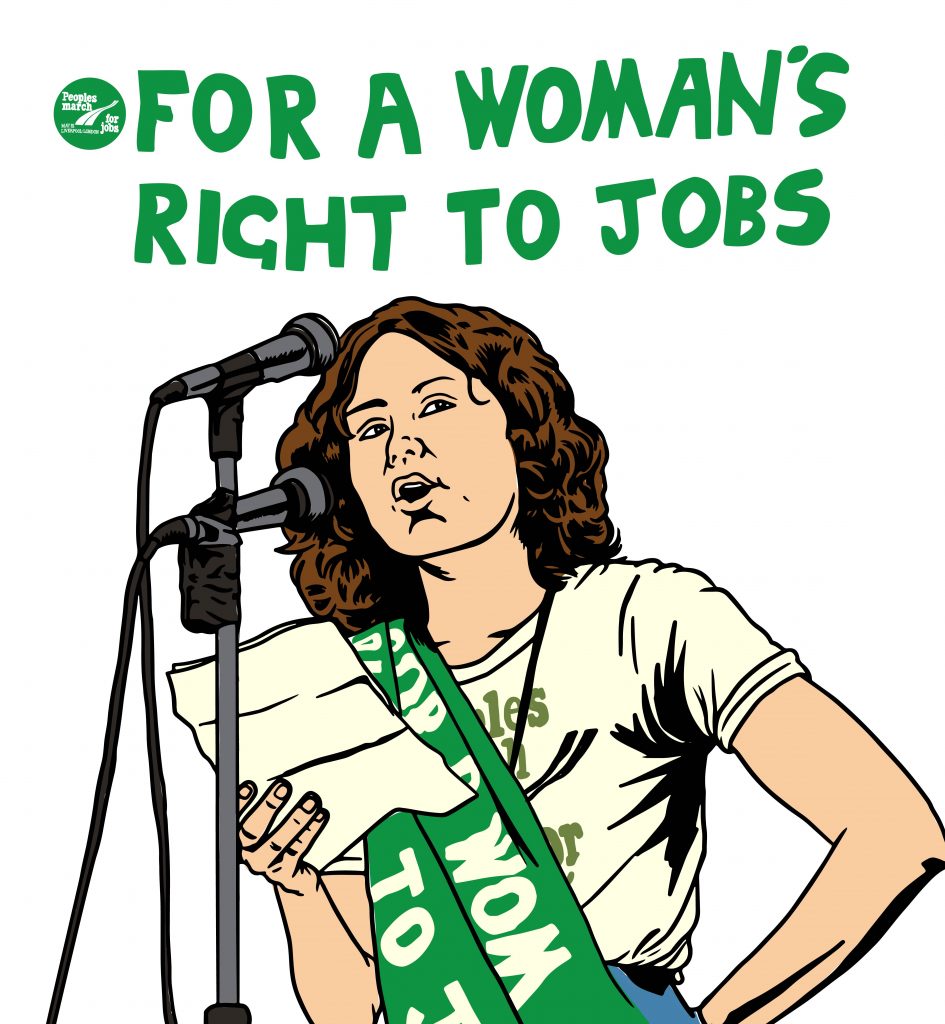

Thatcherism had had a devastating impact on working class women. Social care cuts and the decline of light manufacturing industries saw female unemployment increase by 51%. Despite this, women were poorly represented, with only around 25 on the western leg and ten on the eastern leg: ‘One of the important things for us was that we were going to share the same conditions. Walk the march exactly the same. There was going to be total equality.’ – Catherine Harvey.

Female marchers sometimes faced overt sexism. Stewards initially refused to let them wear sashes in honour of the suffragettes. However, the women of the march made their voices heard. On 25 May 1981, they led a special women’s leg; proudly carrying the march banner into Luton whilst wearing their ‘For A Woman’s Right To Jobs’ sashes.

Predictably, some rightwing press outlets attacked marchers. Organisers were branded anti-democratic Trots, whilst marchers were labelled as workshy misfits enjoying a drunken jolly to London. These myths were easily debunked by correspondents from The Guardian, News Line and the Morning Star accompanying the march.

With the British public lending their support to marchers, the tabloid press was forced to change their stance.

As the two columns made their way through the heart of England, they were enthusiastically welcomed by working class communities. Thousands attended special solidarity rallies in Manchester, Leeds, Birmingham, Coventry and Corby.

It’s fair to say that the campaign had very little impact on Tory policymaking.

After the rally had ended, many wanted the TUC to use the momentum generated to unite workers and the unemployed into a permanent movement that could take down the Thatcher government.

Some marchers helped establish Unemployed Centres in working class communities. Moreover, the march had a profound personal impact on those that took part.

In post-industrial Britain, mass, long term unemployment is no longer a popular rallying cry. Attitudes to job security have been transformed; some would say deliberately.

Recently there has been a renewed right to work movement. Unionised workers are organising campaigns against compulsory redundancies and the offshoring of jobs.

Like their contemporaries in the Green Army, many young people on the left are actively engaging in peaceful direct actions supporting a variety of campaigns. As in 1981, this is vital if we are to provide a counter to a resurgent populist far right.

I sincerely hope the lessons of the march have been learned, and these acts of protest transform into a long-term political movement.

Author profile:

Historian Dr Greig Campbell is a Liverpool based oral historian. His primary research focus is deindustrialisation; producing intimate accounts of anti-closure campaigns conducted by rank and file unionised workers. As a public historian, his practice centres on working alongside community groups in order to document the experiences of marginalised communities.

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM. Images supplied by contributor.

Watch Giz a Job: an oral history of the People’s March for Jobs 1981

Visit So We Marched, a free exhibition on the third floor of Liverpool Central Library extended until 15 June 2024.

Discover material about the People’s March for Jobs in the museum’s archive.

Subscribe to PHM’s regular e-newsletter to keep up to date with our latest blogs and upcoming events, by taking our quick quiz to find out which radical are you?