Ahead of the anniversary of the 1926 General Strike in May, People’s History Museum (PHM) Researcher Dr Shirin Hirsch uncovers the history of the strike, through documents and photographs in PHM’s collection, to explain why a strike in Britain was called and the reason for its collapse just nine days later.

In this country there hasn’t been a national general strike for almost a century so it might sound unusual as a concept. A simple definition of a general strike is a stoppage of labour by workers in all, or most industries. The idea of a general strike is nearly as old as the working class movement. It was first written about by William Benbow, a radical based in Manchester, who in 1832 published a pamphlet calling for a ‘Grand National Holiday’ for the ‘productive classes’. His ideas for a general strike were adopted through the Chartist Convention but were not followed through until 1842 with the Plug Riots, a general strike which first started in Stalybridge and then swept across the rest of Lancashire and Yorkshire. Later, Marxists began to think through the general strike, most significantly in 1906 with a pamphlet by Rosa Luxemburg.

The 20th century saw many general strikes at high points of class struggle, to name a few: St Petersburg in 1904, Spain and São Paulo in 1917, Central Germany, Seattle, Vancouver, Barcelona, Belfast in 1919, Hong Kong in 1922, Palestine, Syria and France in 1936, German-occupied northern Italy in 1944, Nigeria in 1945, East Germany in 1953, Hungary in 1956, France in 1968 and Iran in 1978. And this continued into the 21st century, with one of the largest strikes in world history taking place in India in 2020, with estimates of 250 million people.

This was nine days when Britain came to a standstill. At one minute to midnight on 3 May 1926 the Trade Union Congress (TUC) called for the withdrawal of labour in transport, electricity, gas, docks, heavy chemicals, building and printing, all in solidarity with the miners. This was because a few days before over a million miners had been locked out of work for refusing to accept lower pay and longer hours imposed on them by the coal owners and backed up by the Conservative government. ‘Not a minute on the day, not a penny off the pay’ was the miners’ defiant response.

Almost two million workers joined the 1926 General Strike in sympathy with the miners and the reports from both sides (the government printed the British Gazette and the TUC printed the British Worker, both held in the archive at People’s History Museum) give a sense of how solid the resolve of workers on the ground was. And then, on 12 May, the TUC announced the end of the 1926 General Strike. They had won no guarantees, no written agreements, no conciliatory deals. In fact, many workers simply disbelieved reports that the strike had been called off. ‘Normal’ order would take time to be restored and as a result more workers came out on strike the day after the General Strike had officially been ended.

The TUC had asked the government to guarantee workers returning from the strike would remain employed, but even here the government stated that it had ‘no power to compel employers to take back every man who had been on strike.’ Many of the most militant strikers were victimised and lost their job on return. The leader of the miners, A J Cook, wrote how ‘a complete surrender had been reached’ by the TUC. Cook added, ‘it was more than a surrender on their part. It was an ultimatum to us miners, bidding us surrender, too.’ The miners continued their strike for another seven months, but poverty, starvation and isolation eventually forced their own delayed and bitter surrender, returning to work or unemployment, their conditions worsening into the 1930s. The miners did not have another national strike until 1972, almost 50 years on. This was a defeat of a colossal scale, and it would take a new generation of working class people to move on from its impact.

Globally, the Russian Revolution of 1917, anti-colonial movements, and in 1921 the independence of Ireland from the British Empire, caused deep anxiety within the British elite. There was a fear of contagion, and this radicalism spread to Britain. From the end of the First World War until 1926 there had been a whole series of local and national strikes in Britain, a period with high levels of industrial unrest and a growing syndicalist movement. But the conclusive defeat of the 1926 General Strike signalled the end of an era in modern Britain. Militant trade unionism was replaced with a trade union approach centred on respectability and deference, trade union leaders now embracing a far more conciliatory strategy towards the employers and the government. This can be seen through Walter Citrine, General Secretary of the TUC from the 1926 General Strike onward, first knighted in 1936, then made a Privy Councillor and finally at the end of his TUC tenure made a peer, taking the title Baron Citrine.

The focus for trade union leaders was now much more on supporting the Labour Party and winning parliamentary power. Meanwhile trade union membership seriously declined. On the other side, the victory of the 1926 General Strike gave the Stanley Baldwin Conservative government confidence to further challenge working class pay and conditions, with the trade unions removed as a serious threat. This victory was formalised through legislative change in 1927 with the passing of the Disputes and Trade Union Act prohibiting sympathetic strike action and mass picketing, overturned only after the Second World War by the Clement Atlee Labour government.

The defeat, those nine days in May, also remained etched into the minds of millions of workers and their families for generations to come. The 1926 General Strike challenged the social order, its conclusion was not preordained, and for a short moment the tables were turned on who ran the country. There are many accounts from ordinary people you can read about in People’s History Museum’s (PHM) archive. Here is one memory of the 1926 General Strike from a sheet metal worker in Ashton-under-Lyne who wrote:

‘Employers of labour were coming, cap in hand, begging for permission to do certain things, or, to be more correct, to allow their workers to return to perform certain customary operations. “Please can I move a quantity of coal from such and such a place” or “Please can my transport workers move certain foodstuffs in this or that direction…” Most of them turned empty away after a most humiliating experience, for one and all were put through a stern questioning, just to make them realise that we and not they were the salt of the earth. I thought of the many occasions when I had been turned empty away from the door of some workshop in a weary struggle to get the means to purchase the essentials of life for self and dependents…I thought of the many occasions I had been called upon to meet these people in the never-ending struggle to obtain decent conditions for those around me, and its consequent result in my joining the ranks of the unemployed; of the cheap sneers when members of my class had attempted to rouse consciousness as to the real facts of the struggle…Now the cap-in-hand position reversed.’

There are many competing theories and narratives, but there are some explanatory factors. Firstly, the government were extremely well prepared, having delayed the 1926 General Strike by nine months. In July 1925 the unions had announced ‘Red Friday’ as a victory for their side, as the government agreed to temporarily subsidise the mining industry to maintain miners’ wages. The Samuels Commission was launched by the government to supposedly investigate the question of the miners, but in reality, this was a clever delaying tactic by Prime Minister Baldwin. It meant that during the time that had passed the coal owners built up their coal stocks. The government developed their propaganda, presenting the unions as a threat to the rule of law and constitutional government; as Baldwin put it, the 1926 General Strike was ‘the road to anarchy and ruin’. In addition, the government formed the Organisation for the Maintenance of Supplies where thousands of people, mainly middle and upper class, signed up to volunteer in the event of a general strike, led by a former viceroy and governor general of India Lord Hardinge.

On the union side, however, it appeared there was almost no preparation for the 1926 General Strike, even though its occurrence was not a surprise. Union leaders like J H Thomas of the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR) were desperate to avoid a general strike, and instead of preparing union forces for confrontation he spent his time, even during the strike, trying to call things off with no focus on winning. In parliament, the day after the strike was ended Thomas (also MP for Derby) explained to his peers “what I dreaded about this strike more than anything else was this: If by any chance it should have got out of the hands of those who would be able to exercise some control, every sane man knows what would have happened. I thank God it never did.”

In Britain’s national culture, conflict is often remembered as an external phenomenon across borders. Wars between Britain and foreign nations are central to official sites of memory. Conflict internally, inside the nation, is less formally remembered and is often smoothed over or forgotten entirely. The 1926 General Strike is one such case, a momentous event in 20th century Britain, yet, amongst the victors at least, there is little interest in remembering its significance. The day after the strike, Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin explained to parliament that “our duty is to escape as soon as possible from the consequences of this unhappy controversy” and that “the less we talk about it…the better are our chances of success.”

But the 1926 General Strike was not forgotten, and particularly in mining communities it was bitterly remembered during the depression years of the ‘hungry thirties’. Later, filmmaker Ken Loach made a TV series on the longer history culminating in the 1926 General Strike, Days of Hope (1975), broadcast on the BBC. In 1976 the anniversary was tied into a wave of new miners strikes and industrial militancy. An exhibition to mark fifty years since the 1926 General Strike was held in Covent Garden.

Almost one hundred years later, much has changed. During the 1926 General Strike university students were mainly from wealthy backgrounds and many volunteered to break the strike. Today, university students are more likely to be seen in solidarity with workers on the picket lines. During the 1926 General Strike coal was Britain’s main source of energy and the miners were therefore a hugely powerful workforce. Coal and the miners are now no more in Britain. The working class in this country are more likely to be found in large warehouses, in call centres, in schools, supermarkets, care homes and hospitals. Transport workers were important during the 1926 General Strike and their significance remains today, although there are now also delivery drivers on electric bikes transporting commodities quickly. Despite changes to the working class, the issues the strike was fought over – low wages, long hours, bad contracts, and broader ideas of workers power and solidarity, have not gone away.

Book an appointment to discover more of the collection with the Archive Team via archive@phm.org.uk. Check out the 1926 General Strike archive guide.

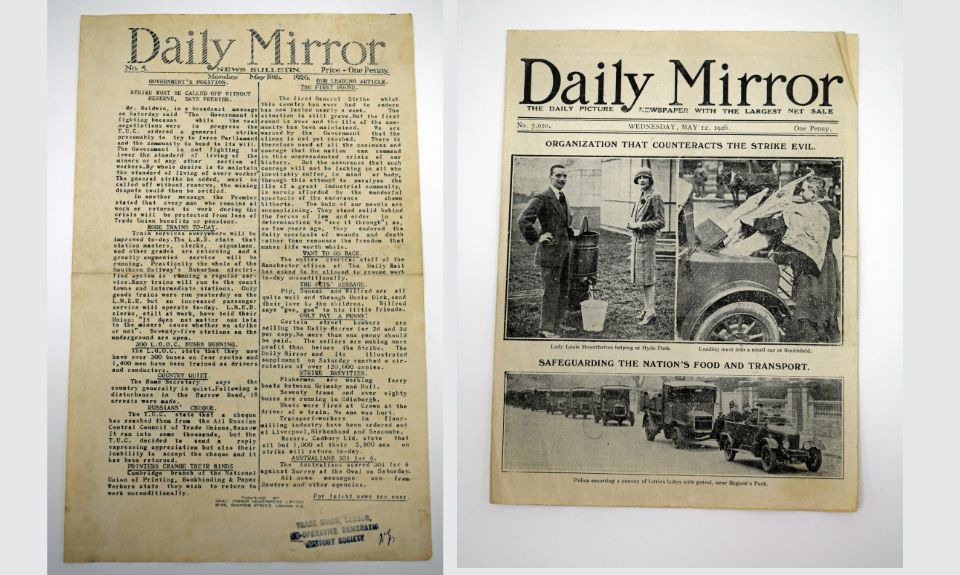

Visit the museum’s galleries, which include a small 1926 General Strike display with artefacts from the strike including truncheons used by special constables, newspapers including the Daily Mirror and The New Leader, a ceramic figure made on the day the strike collapsed, a telegram announcing the end of the strike, as well as miners’ lamp badges used for fundraising for miners and their families.

Watch Sara from PHM’s Visitor Experience team talking about her favourite PHM object. In this reel she explains how volunteers were recruited to help break the 1926 General Strike, including a student who received a gift for his work.

Read blogs about Shapurji Saklatvala MP and Ellen Wilkinson MP who were both thrown into the midst of the struggle during the 1926 General Strike.

Sign up to receive our e-news and be amongst the first to find out how PHM will be marking the centenary of the General Strike in 2026.

General Strike 100

PHM are currently working with the General Federation of Trade Unions (GFTU) and a group of museums, libraries and archives to co-ordinate the general strike centenary celebrations:

Beamish, the Living Museum of the North, Campaign for Trade Union Freedom, the Crab Museum, General Federation of Trade Unions, National Coal Mining Museum for England, People’s History Museum, Radical Tea Towel Company, Society for the Study of Labour History, Strike Map, TUC Library Collections — London Metropolitan University, Working Class History and Working Class Movement Library.

If you want to support this project, please consider donating via www.bit.ly/GeneralStrike100