100 years ago in the 1922 general election the Labour Party elected Shapurji Saklatvala as their first MP of colour. We asked PHM’s Researcher Dr Shirin Hirsch to tell us more about the MP Saklatvala, missing from the official histories of the Labour Party; from his early life and membership of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), to his fight for national and colonial issues in parliament.

‘one of the most violent anti-British agitators in England…’

‘that notorious enemy of the British Empire…’

This was how Shapurji Saklatvala was described, first by the British secret services and then by the Public Prosecutor at the Bombay Police Court in 1927.

Shapurji Saklatvala was born in 1874 into a wealthy Parsi family in Bombay (what is now Mumbai). The Indian subcontinent was ruled under a colonial system directly administered by Britain but with a hierarchy of Indian groups within this. The Parsis were followers of the Zoroastrian faith and during British colonial rule they were given posts of trust and seen by colonial administrators as closer, although not equal, to their white rulers. Saklatvala’s Parsi family included his uncle, J N Tata, founder of the Tata group, India’s first industrial millionaires.

After finishing college, Saklatvala worked for his uncle’s business where he led expeditions that unearthed iron and coal. During this period Saklatvala began to question the British Empire and its governance. He later recalled in parliament how, during a plague in 1902, he visited a professor in a European club to discuss preventative measures to the plague for his workforce. He was barred from entering the club because he was not white and instead led secretly through the backyard and through an underground passage to a basement room where the professor could talk to him. This was just one experience of many where Saklatvala began to question the injustices of the colonial system.

Saklatvala’s uncle had been an Indian nationalist, but when he died his son Dorabji Tata took over and the two cousins disagreed on much, not least Dorabji’s Anglophilia. When Saklatvala became ill with malaria he was sent away to England to manage the family’s Manchester office.

In England Saklatvala joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) in 1909, drawn to ideas of equality and socialism. He had intended to return to India, but in Matlock, Derbyshire, he met a waitress, Sarah Marsh, and their marriage and children kept him in England. In 1917 the Russian Revolution shook the world. In Britain the impact of the Revolution was described by the Prime Minister, Lloyd George, as a ‘new infection’ which ‘encouraged all the habitual malcontents in the ranks of labour to foment discord and organise discontent’. Saklatvala, embedded now in ILP networks, was one of these malcontents hugely inspired by events in Russia.

In 1919 the Communist International was formed and Saklatvala, like many others in the ILP, worked hard for his organisation to affiliate. He was not successful, however, and in 1921 he left the ILP. He was now a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), but he was also a member of the Labour Party; the two organisations were not yet in direct opposition.

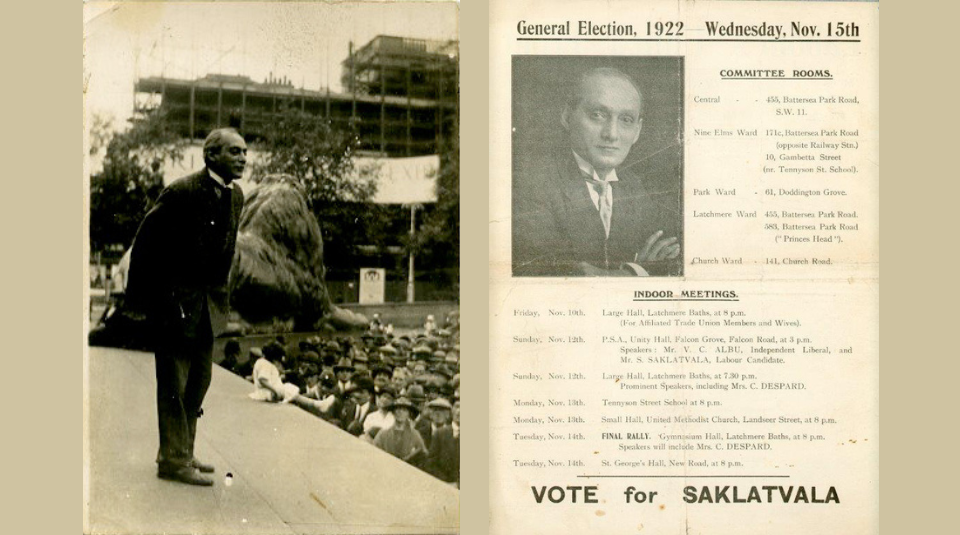

In 1922 a general election was called. Saklatvala was nominated as the official Labour Party candidate for Battersea North in south London, an unusual occurrence since he was openly a CPGB member. Battersea North was a radical constituency with a large Irish population, and Charlotte Despard, the suffragist, socialist and later Sin Fein activist, had been the Labour candidate before Saklatvala. In 1913 Battersea had elected a black mayor, John Archer, a Pan-Africanist and the first black person to hold a senior public office in London. Archer became Saklatvala’s election agent. Anti-imperialism was a significant political current in Battersea that Saklatvala was able to tap into. He won the 1922 election and became the Labour and Communist MP for Battersea North, making him the first MP of colour to be elected in this history of the Labour Party.

Once elected, Saklatvala used his position in parliament to immediately oppose the partition of Ireland, voting against the Irish Treaty and calling for a free and united Ireland. But his biggest focus in parliament was India, the place of his birth, and as early as 1922 he was being described by the press as the ‘Member of Parliament for India’. Saklatvala was comfortable with this title, as he saw himself as MP for Battersea North and workers of the world. For him, socialism meant the destruction of the British Empire; workers could not be free in Britain without the violent binds of Empire first destroyed. As he explained to one newspaper, he had electorally pledged to ‘not devote himself to the welfare of the local cricket club…’ but instead to national and colonial issues in parliament.

Another general election was called quickly in 1923 and this time the press attention on Saklatvala was immense, with a focus on the ‘red revolutionary’ and his relationship to the Labour Party. The Daily Mail argued that the Labour Party were not British but more in throws with the Russian Bolsheviks. The paper noted that Saklatvala proposed not just one capital levy but a succession of capital levies to distribute wealth away from the rich. The Times argued that Saklatvala’s ‘pernicious influence’ had ‘crept like duck-weed among a large section of the electors, whose discontent has been created or fed by unemployment.’ Saklatvala lost the election in 1923, but in 1924 another election was called.

This time, the Labour Party annual conference had just passed a resolution expelling CPGB members from the Labour Party. Despite this, the local Labour Party and trades council in Battersea decided to back the CPGB member Saklatvala. He won the election and continued as MP for Battersea North until 1929 when he lost (this time against an official Labour Party candidate).

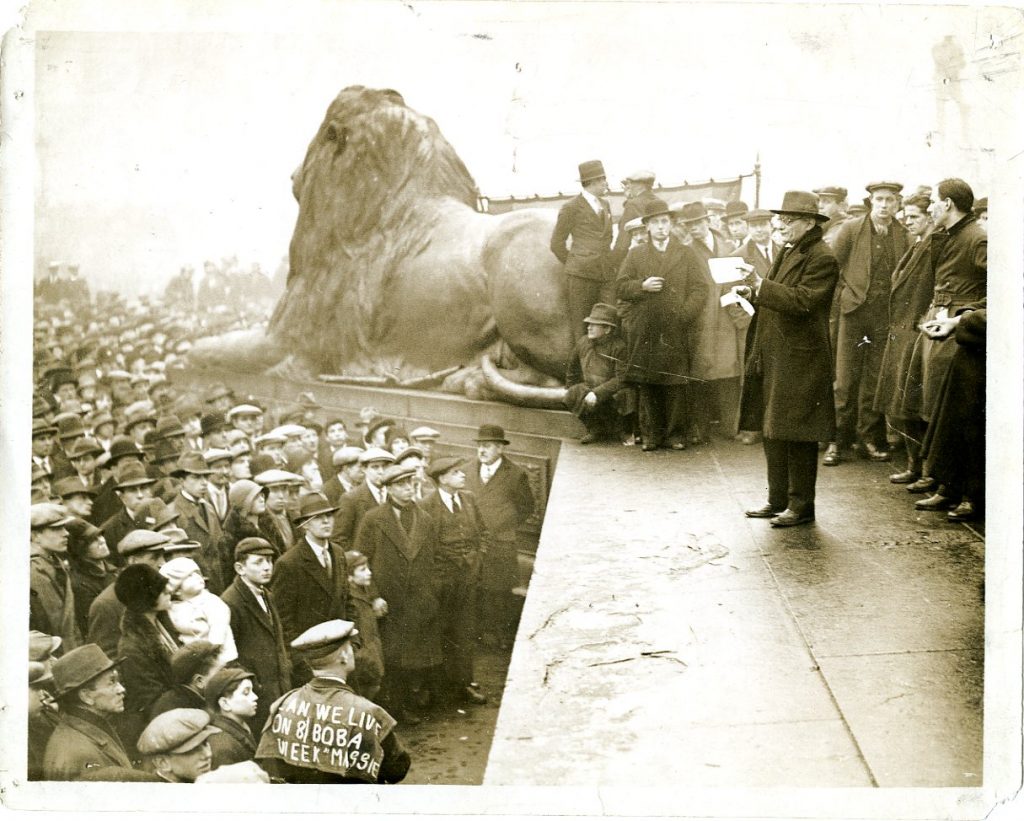

Throughout his time as an MP Saklatvala was hated by the press not just because he was an open communist, but also because he had migrated from India and yet dared to speak out against the British Empire inside its most venerated institution, parliament. The papers often referred to him as an ‘Imported Oriental’. The Daily Mail argued Saklatvala had the temerity to denounce the Crown, the law, the Empire, the nation, and the flag. In an article in 1925 the paper wrote that ‘nor could any Moscow commissary hate the British Empire more rabidly than Battersea’s Indian MP Mr Saklatvala. He avows himself, frankly, a determined and implacable enemy of the Union Jack and British Imperialism.’ Saklatvala, however, was a hugely popular speaker. This was often explained through racial descriptions where he was both mysterious and dangerous, with one paper describing him as a Parsi with a knowledge of black magic, so influential was he on his constituents, wielding a ‘magnetic influence over his audience that verges on hypnotism’.

This hostility had practical implications. In 1925 Saklatvala planned to go the United States as a member of the British delegation to the inter-parliamentary conference, but there was a concerted campaign to stop him, with other MPs refusing to travel with Saklatvala, and eventually the Secretary of State, revoked his visa on the grounds that the United States did not admit revolutionaries. In 1926, on the eve of the General Strike in Britain, Saklatvala called on soldiers not to shoot their fellow workers; he was arrested, on charges of sedition, and although his friend George Lansbury (British politician and social reformer who led the Labour Party from 1932 to 1935) paid his bail, his trial was rushed through and he was imprisoned for two months.

In 1927 Saklatvala organised a speaking tour across India, where he condemned British rule in India as the lynchpin of ‘our people’s perpetual starvation, ignorance, physical deterioration and social backwardness.’ The response across the country was huge and many Indian cities even agreed to give Saklatvala an official welcome. He also met with Ghandi, and the newly established Communist Party of India, as well as meeting two British party members who had been sent by the CPGB in support. You can read more about this and the Meerut trial in PHM Collections Assistant Shivaya Prasad’s blog, Journeys of Empire. Saklatvala’s tour lasted for three months and was recognised by the British Foreign Office as a great success, so much so that they successfully agitated to remove the validity of Saklatvala’s passport for India. Saklatvala was never allowed to return to the place he was born and this was upheld even during the second Labour Party government of 1929 to 1931.

Saklatvala died in London in January 1936. He was cremated at Golders Green, just a few hours before author Rudyard Kipling’s funeral in the same spot. But whereas Kipling famously wrote how ‘East is East and West is West and never the twain shall meet’, Saklatvala’s life was a deep intertwining of the two, his politics illuminating how liberty could only be gained in the west through the self liberation of those in the east. When the Spanish Civil War broke out and people in Britain joined the International Brigades, the British Battalion was named in honour of Saklatvala. Today, there are no statues to remember Saklatvala outside parliament, and, despite being the first Labour MP of colour, he seems all but forgotten in official histories of the Labour Party.

In the museum’s Labour History Archive & Study Centre you can read original documents recording Saklatvala’s political life. In the heart of Empire, Saklatvala made it his life work to attack, expose and abolish the colonial structures that shaped his world. With ongoing debates on ‘decolonisation’, it is worth returning to and learning from Saklatvala, who fought for a radical project to end the British Empire.

Dr Shirin Hirsch

Shirin is a historian based jointly at PHM and Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU). She specialises in the history of modern Britain with a particular focus on the labour movement, race and Empire. Shirin’s current work at the museum focuses on decolonisation, and her research is exploring resistance to the ‘colour bar’ in Britain.

With thanks to archive placement students Sophia Riley and Ben Perry for sourcing the images.

Listen to Shirin discussing Saklavata for Little Moscow, on BBC Radio 4 with Presenter and Historian Camilla Schofield. Part of a three-part series Britain’s Communist Thread.

In the museum’s archive, see material from the 1922 election including a copy of the Labour Party’s manifesto which included progressive policies such as a special levy on the super-rich to pay for debt incurred during World War I, nationalisation of railways and mining, and recognition of the independence of Egypt and self-governance for India.

The museum’s internationally significant collection includes items of national importance from the last 250 years of British social and political history. Home to the complete holdings of the national Labour Party and Communist Party of Great Britain and over 95,000 photographs relating to the growth of democracy in Britain, covering not only parliamentary reform, extension of the vote and general elections, but grassroots organisations and campaigns also.

People’s History Museum is open from 10.00am to 5.00pm, every day except Tuesday. The archive is open Wednesday to Friday, 10.00am until 4.00pm (lunchtime closure 12.30pm to 1.30pm). Booking essential.

Keep up to date with PHM’s latest blogs and upcoming events by taking the Radicals quiz to sign up to our regular e-newsletter.