80 years ago, on 5 July 1945 the Labour Party won a landslide general election. We asked PHM’s Archives Officer, Darren Treadwell, to tell us more about elections during wartime and the 1945 general election. His insight is illustrated with campaign, political and election material from the museum’s rich collection of materials from the Labour Party archive.

The 1940 general election was due to take place sometime during the summer or autumn of 1940, with the previous election having been in November 1935, but it did not take place.

On 10 May 1940 Winston Churchill was appointed Prime Minister of a coalition government. He was helped into power by the Labour Party under Clement Attlee.

At the start of the Second World War the Labour Party were willing to serve in a coalition government, but not under Neville Chamberlain who was the Prime Minister at this time. Attlee sought the votes and advice of the parties’ National Executive Committee, which was starting to gather in Bournemouth for its annual conference. It was agreed that Labour would back a coalition government with Attlee as Deputy Prime Minister.

The very same day Churchill was appointed Prime Minister, German armies invaded France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and The Netherlands. It may well be difficult to understand today, but given the desperate state the country was in during May, June, and July of 1940 the cancellation of a general election would almost have seemed trivial.

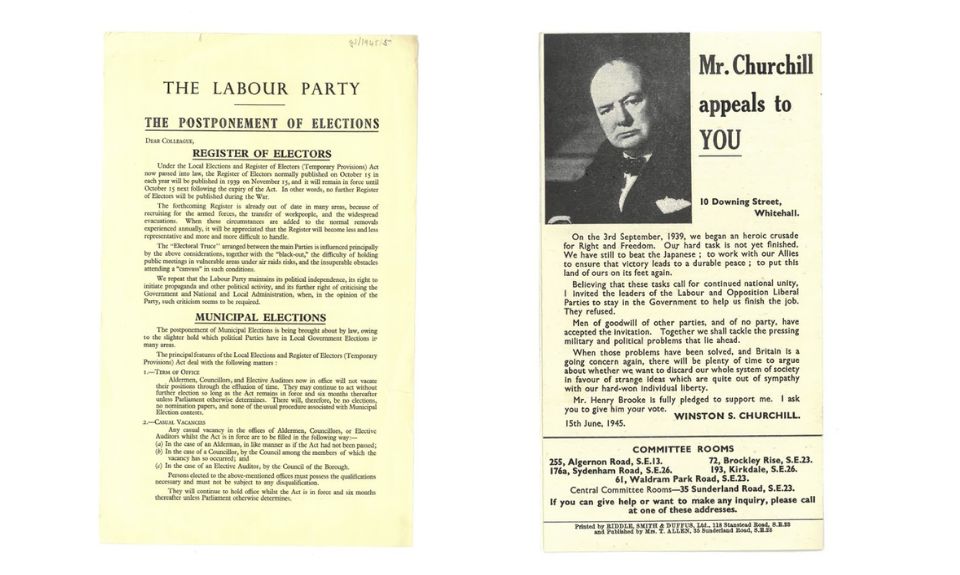

Left to right – The Labour Party, postponement of elections leaflet, May or June 1939 and MP Henry Brooke Conservative general election campaign leaflet, 1945. Image courtesy of People’s History Museum

Victory in Europe over Germany was declared on 8 May 1945, whilst the war against Japan was still being fought and would continue until Japan’s unconditional surrender on 15 August 1945.

During the period of victory over Germany it is surprising just how quickly the coalition fell apart.

Churchill had wanted the government to stay together until victory over Japan, but many in the leadership of the Labour Party were restless. These feelings coincided with the Labour Party’s annual conference, which was held in Blackpool between 21 and 25 May 1945. It was here that the National Executive Committee voted to leave the government.

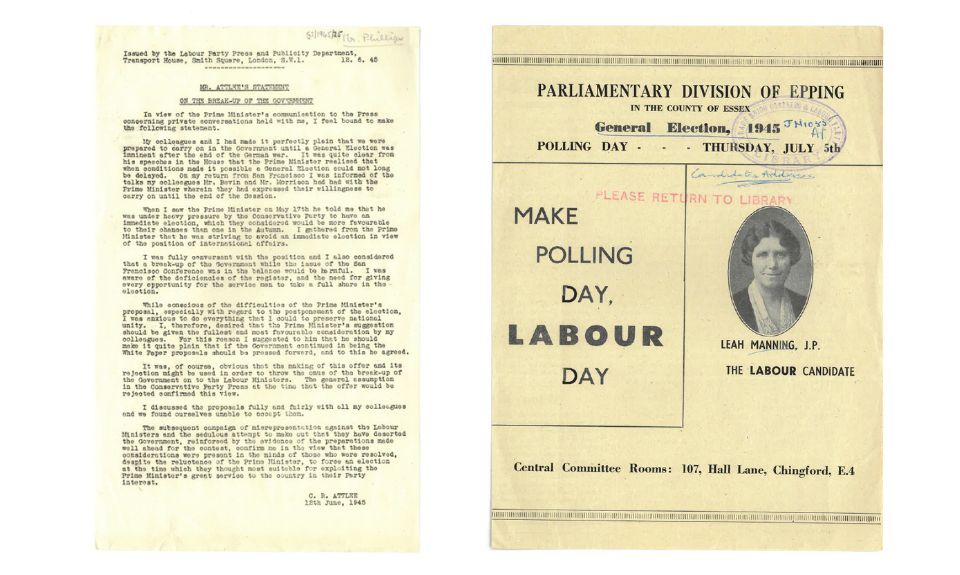

Left to right – A copy of Clement Attlee’s statement on the break-up of government issued by the Labour Party press and publicity department, 1945 and Leah Manning JP general election candidate leaflet, 1945. Image courtesy of People’s History Museum.

The first general election for a decade (the previous, 14 November 1935) would take place on 5 July 1945. The result, however, was not to be announced until 26 July 1945, and there are several reasons for this.

Men and women who were abroad in the armed services had to have their votes sent home and counted as part of their local vote. There were also the now largely forgotten ‘Wakes Weeks’ which would involve whole towns across Lancashire each taking a different week off between June and September. Consequently, extra polls were held in different towns on both 12 and 19 June 1945, with the rest of the country voting on 5 July 1945. It was then that the ‘Wakes Weeks’ votes were counted.

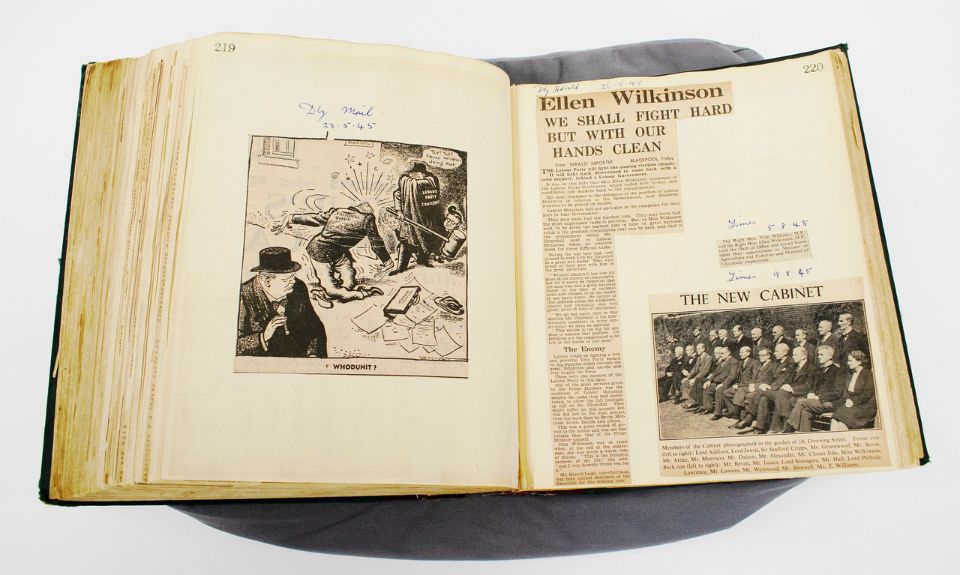

The new cabinet. Ellen Wilkinson MP scrapbook, 1930-1947. Image courtesy of People’s History Museum.

The Labour Party was very well prepared for the 1945 general election. Four years of solid preparation, research, committee meetings, memos, and speeches. All of this was the work of the Committee for Reconstruction, which started in March 1941 to look into the shaping of the post-war world. There was a broad overarching general committee then separate committees for subject areas – health, housing, education, reconstruction of mining, gas, electricity, transport and steel, also science and scientific research, legal reform, plus New Towns construction.

The Labour Party Research Department and Committee for Reconstruction spent most of the war preparing for peace. What runs through the literature the party produced for the election campaign is a very strong sense of sacrifice, followed by the need for renewal. The manifesto is called ‘Let us Face the Future’ and the most famous election poster is ‘And now Win the Peace’, but the crucial reference is the 1930s and the years before the war.

What people feared most, and it was fear, was unemployment – a return to the colossal, unmeasurable, social waste of millions of men and women without work. There was to be no return to that, and it is this mass unemployment, and doing very little in the way of trying to alleviate it, that the Conservative Party was most associated with at the time in the public’s mind.

The campaign itself, the second half, was quiet in many ways. The only real controversial moment came when Churchill said that implementing some of the measures the Labour Party had in its manifesto would require some form of Gestapo, and regardless of how distasteful, it never really affected the outcome.

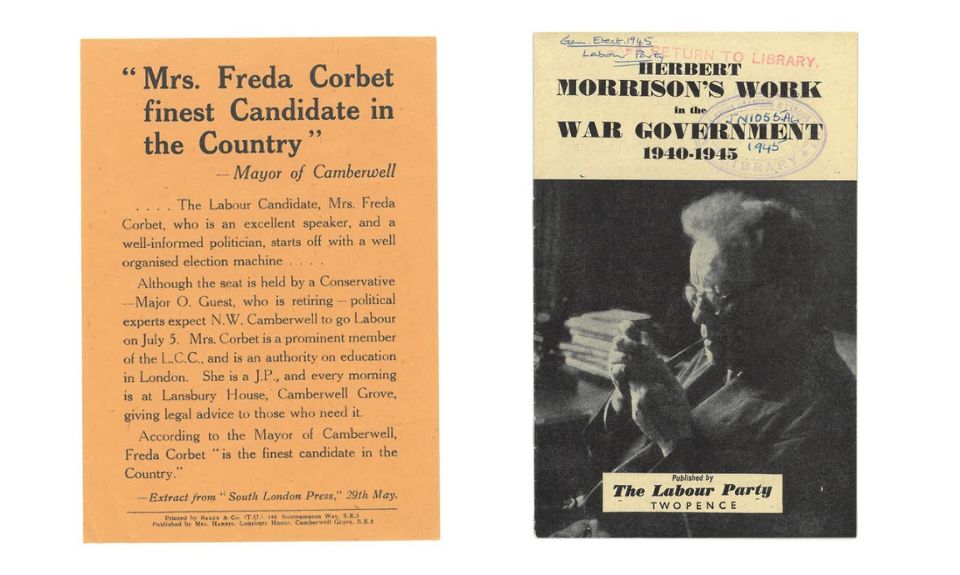

Left to right – Labour candidate Mayor Freda Corbet general election flyer, 1945 and Labour candidate MP Herbert Morrison’s general election pamphlet, 1945. Image courtesy of People’s History Museum

There is an area that often gets neglected when looking at the 1945 general election, which is that for around twenty percent of voters it was the first general election that they had ever voted in.

This writer can use the example of their own grandparents; all four of them were born in 1920, and so in 1935 they are far too young to vote. But by the time it gets to 1945 they are all 25 years of age and have behind them a decade of mass unemployment, very poor housing, the constant search for work, and this is followed by five years in the army away from home in Libya, Egypt, Italy, Greece, France, Belgium, and Germany. Years in munitions factories and the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) – it’s not strange that people in their millions voted with a sense of wanting to leave the past behind and look towards a better future.

Darren Treadwell is part of PHM’s expert Archive Team helping researchers explore our incredible collection of political archive material.

The museum’s internationally significant collection includes items of national importance from the last 250 years of British social and political history. It is home to the complete holdings of the national Labour Party and Communist Party of Great Britain and over 95,000 photographs relating to the growth of democracy in Britain, covering not only parliamentary reform, extension of the vote and general elections, but grassroots organisations and campaigns also.

The archive is open Wednesday to Friday, 10.00am to 4.00pm, lunchtime closure 12.30pm to 1.30pm.

General election banner, 1906. NMLH.2019.45. Image courtesy of People’s History Museum.

Book an appointment to see the archive collection with the Archive Team via archive@phm.org.uk. The collection at PHM is full of examples of election pamphlets, leaflets, posters and cards from 1900 onwards.

Visit the museum and open the ballot boxes around the galleries to discover how voting reforms shaped who can vote and how we vote. Starting with the Reform Act of 1867 to the introduction of voter ID in 2022.

Read blogs about the 1922 general election when the Labour Party elected Shapurji Saklatvala as their first MP of colour, the life of one of the first female Labour MPs Ellen Wilkinson who became Minister of Education in the post Second World War Clement Attlee government, and 20 general elections with incredible objects from PHM’s collection.