By Dr Shirin Hirsch, Researcher at People’s History Museum and Lecturer at Manchester Metropolitan University

On 16 August 1819 60,000 people congregated in St Peter’s Field in Manchester, with demands for the right to vote, freedom from oppression and justice. Despite its peaceful beginning, this was a day that would end with a bloody outcome.

From Waterloo to Manchester

In 1789 the French Revolution shook the world and the ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity spread rapidly. In Britain, less than 3% of the population could vote and the system was entirely corrupt. The ideas of the French Revolution were therefore eagerly received and most powerfully expressed in Thomas Paine’s book, the Rights of Man (1791). Paine’s words inspired ordinary people to question the systems they lived under, systems that had been challenged by those across the channel. The British government prepared for war not simply to defeat the revolutionary ‘menace’ in France, but also to destroy the revolutionary ‘menace’ in Britain that Tom Paine had helped unleash. Britain eventually won the Napoleonic Wars (1803 – 1815) against France, but at great expense and with a huge national debt. Moreover, the militant ideas from France lived on. Returning British soldiers, like John Lees who was a veteran of the victorious battle of Waterloo, were now living not in the prosperity of the victor, but in poverty. Lees came from Oldham and when he returned home he continued his trade as a cotton spinner, but now with drastically reduced wages. Lees was one of those who protested in Manchester on 16 August 1819 and, having survived the battlefield, was to lose his life at the hands of his own army in the Peterloo Massacre. In the days that followed, the massacre was named ‘Peterloo’ by a journalist in a mocking reference to the celebrated victory at Waterloo in the Napoleonic Wars that Britain had fought. Lees’ dying words to his friend were, at ‘Waterloo there was man to man, but at Manchester it was downright murder’.

Representation

In the context of poverty and the huge numbers of working people pushed into the industrial centres in and around Manchester, a reform movement demanding the right to representation captured the minds of large numbers of ordinary people. Despite the growing population of Manchester, there was no MP to solely represent the area. A demonstration was called in Manchester, which by being postponed to Monday 16 August 1819, meant people were readily prepared for it. A Monday seems a strange day to choose, yet for the handloom weavers, who were still the majority in the cotton trade in the area, after working all weekend they traditionally took Mondays off. These workers, who feared for their jobs and standard of living, made up a large component of the protestors.

Preparing for the protest

The industrial towns surrounding Manchester put huge efforts into the preparations in the weeks beforehand and contingents from each area had different creative responses. Oldham’s centrepiece was 200 women in white dresses and a banner of pure white silk, emblazoned with inscriptions including ‘Universal Suffrage’, ‘Annual Parliaments’ and ‘Election by Ballot’. They marched to Manchester through the moors, joining the Saddleworth group, whose banner was pitch black with the inscription ‘Equal Representation or Death’ over two joined hands and a heart. These words would be used by the magistrates after the massacre to justify their actions. The banner, the magistrates argued, was a clear sign of revolutionary intent.

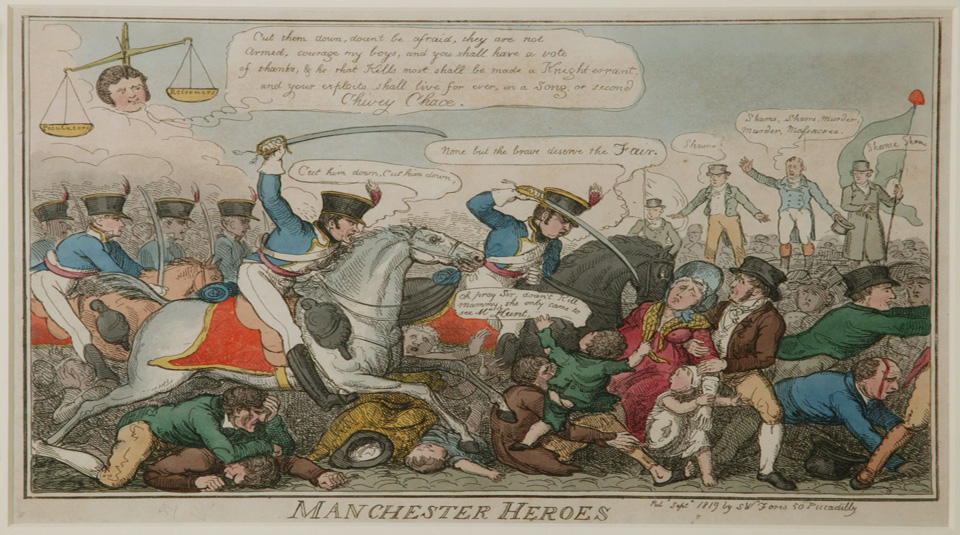

How a peaceful protest met with violence

The protestors were peaceful and unarmed. The weaver and reform leader Samuel Bamford wrote later how the drilling of the Middleton contingent in the build up to the demonstration meant that, on the day, every hundred men and women had a leader whose order they were to obey and each leader had a sprig of laurel in their hat as a ‘token of amity and peace’. On arriving in St Peter’s Field, an observer described ‘large bodies of men and women with bands playing and flags and banners…There were crowds of people in all directions, full of humour, laughing and shouting and making fun. It seemed to be a gala day with the country people, who were mostly dressed in their best and brought with them their wives…’ The crowds waited in eager anticipation to hear the principal speaker of the day, Henry Hunt. According to witnesses, tens of thousands of people waited in the square, so tightly packed together that ‘their hats seemed to touch’. In an overlooking building, staring down on the scene, were the magistrates. After two hours of observing, they gave the orders to the enforcers of law surrounding the crowd that the protesters must be dispersed, while the radical reform leaders were to be arrested. On hearing these orders, the recently formed, Manchester and Salford Yeomanry pulled out their sabres and charged the crowd on horseback. The first victim of the attack was a two year old child, William Fildes, who was thrust from his mother’s arms when she fled the cavalry. At least 18 people were killed, of whom three were women, and almost 700 were injured; 168 of these were women even though in numbers they comprised only 12% of those present.

Women at Peterloo

Historians have noted that women were disproportionately targeted at Peterloo; their presence shocked the establishment, challenging the prevalent ideas of women as subservient and domesticated wives. While the reform movement called for the vote for men (under the slogan ‘Universal Suffrage’), women were beginning to organise and even to take a lead within the movement, with female reform groups emerging across Lancashire. As President of the Manchester Female Reform Society, Mary Fildes was the most prominent woman. On the day of the massacre she stood on the stage as a key figure next to Henry Hunt. When the yeomanry attacked, she was slashed across her body and seriously wounded. Mary Fildes would go on to have a role in the emerging Chartist movement, yet so many other women who also took a leading role in the reform movement of this period are little discussed in our history.

Legacy of the Massacre

The British government was keen to cover up the massacre, imprisoning the reform leaders and clamping down on those who spoke out against the government. Within days the massacre was being reported upon both nationally and internationally. However, with the implementation of the new Six Acts legislation, it became extremely dangerous to even publish words that discussed the Peterloo Massacre, and taxes on newspapers were increased so that working class people would be less likely to read them. When Percy Bysshe Shelley heard of the massacre, he penned the poem The Masque of Anarchy, powerfully indicting those who were responsible. Yet Shelley could not find a publisher brave enough to print his words, with the genuine threat of imprisonment hanging over radicals in this period. It was only in 1832, after Shelley’s death, that the poem was first published, and the new Chartist movement would take up his words with gusto.

2019 marks 200 years since the Peterloo Massacre; a major event in Manchester’s history, and a defining moment for Britain’s democracy. A moment when ordinary people stepped up to protest in a way that has made its mark in history and with a legacy that lives on to today.

Disrupt? Peterloo and Protest exhibition is at People’s History Museum (PHM) from Saturday 23 March 2019 until Sunday 23 February 2020. The exhibition is supported by The National Lottery Heritage Fund.

PHM is open seven days a week from 10.00am to 5.00pm, and is free to enter with a suggested donation of £5. Radical Lates are the second Thursday each month, 10.00am to 8.00pm.