To complement the display of a portrait of Hugh Hornby Birley, who as captain of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry played a central role in the events that unfolded at the Peterloo Massacre, we asked author Jeff Kaye to share his research on Birley from his forthcoming novel All the People and treat us to an excerpt about the painting, now in People’s History Museum’s (PHM) collection.

‘It may be hard for us to imagine the carnage at St Peter’s Field at the Peterloo Massacre on 16 August 1819, when the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry led by Captain Hugh Hornby Birley rode into the crowd, sabres cutting, killing men, women and a child, injuring almost 700.

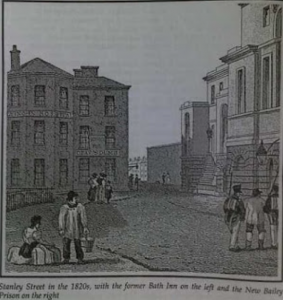

Thereafter, the survivors and their supporters who wished to commemorate the tragedy of Peterloo were not allowed near the site of their grief. The field was blockaded by the 15th King’s Hussars, the regiment that supported the yeomanry into battle in 1819, stationed nearby at Hulme Barracks.

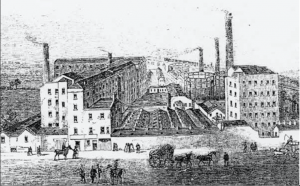

Therefore, on each anniversary of Peterloo, crowds of working people would gather outside a house in Mosley Street and also at Chorlton Mill, now apartments at the junction of Cambridge Street and Hulme Street. There, they would jeer at the symbols of the man that led the charge at Peterloo, the faceless buildings owned by Hugh Hornby Birley.

The authorities considered him guiltless and it was not until April 1822 that a private prosecution was brought by Thomas Redford, a Middleton hatter, against the promoted Major Birley and others, for ‘assault’ at St Peter’s Field. The prosecution failed and Birley must have believed that, at 44 years of age, the shadow of Peterloo had lifted.

Birley was already a successful businessman in Manchester, based on the success of Chorlton Mill, the area’s main employer. He was also a civic leader, the founder of the Manchester Chamber of Commerce and spokesman for the Manchester Association of Master Manufacturers. He used this platform to vigorously oppose Ten-Hour reform: his reputation as the harshest of employers was well earned. He also despised interference by the state into his private affairs, except for the wholesale reduction of the tax on corn because he considered taxation was required to fund his cherished military.

As the Treasurer of the Lying-in Hospital (later transformed into St Mary’s Hospital on Oxford Road, Manchester) for 30 years, he may also have considered himself a philanthropist, if a giver of time rather than his money. But this was insufficient to persuade working people to suspend their hatred. Indeed, many of Birley’s own class thought him contemptible, including Archibald Prentice, Editor of The Manchester Times newspaper and Founder of the Anti-Corn Law League with Richard Cobden. Cobden donated land at St Peter’s Field for the building of the Free Trade Hall; considered a cenotaph to Peterloo and a snub to Birley.

Birley attempted to build a wall of respectability to change memories. His business activities, work for the town and his philanthropy were likely designed, at least partly, to alter how he was remembered rather than compensate for any guilt, which he never admitted. Such efforts were doomed to fail. In 1842, cotton mill workers, striking over starvation wages and the Chartist cause of universal suffrage, came to Chorlton Mill. Throughout the Plug Plot Riots of 1842, other mills across the North West closed without a fight, but Birley’s mill was defended vigorously against the strikers with water hoses fired and masonry thrown from the roof, causing the death of a young girl. The mill was nevertheless closed.

As the strikes ebbed, the Northern Star newspaper, in its Peterloo commemoration edition of 20 August 1842, printed the engraving published by journalist and agitator Richard Carlile of the Peterloo Massacre on its front page with the description, ‘The accompanying engraving represents the horrible scene, just when the ‘heroes’ were hard at work. Let the ‘heroes’ look upon it and refresh their memories respecting their courageous ‘deeds in arms’.’

Feargus O’Connor, the newspaper’s Editor and Chartist leader, listed all the members of the yeomanry present on 16 August 1819, headed by: ‘Hugh Hornby Birley, Commander.’

In my forthcoming novel, All the People, a story of the fight for survival and universal suffrage by the people in Manchester, the heart of the industrial revolution, Birley reads the article in shock. He had decided to return permanently to Broom House, his country home in Weaste in Salford together with his painting that had hung in his office. He knows that his life’s efforts to erase the memory of one terrible act have been futile and rips the newspaper to pieces with a knife, then:

‘He walked to his painting…Yes, he had looked mightily content with himself, he thought, all those years ago, self-confident and secure, almost overbearing in his towering self-belief. Yet now, as he reached into his final years, he was conscious of an insecurity that he had never allowed to surface.

He was standing with some difficulty, exhausted, shaking with the strain of life pressing on his shoulders. He inched closer to inspect the painting. It showed a man in his prime, at the height of his physical wellbeing, he thought, yet with eyes that could not look into his own.

He wondered how he would be painted now? His physical form would show him fatter, for certain; redder of face, definitely; balding, of course. But, underneath the external signs of ageing, how would the artist seek to show the inner self? Would he portray the man of destiny, the yeoman, forever undertaking what was right and proper for God, his King and his country? Or would he betray the man, maltreated throughout his life, misunderstood, drenched in a guilt that he would never acknowledge, eyes unwilling to make contact with even the artist himself?

Birley shuddered at an image that he no longer recognised. His shaking grew in intensity … He still had the knife in his hand. “Perhaps,” he said, “I should lance the boil of history.’

It is ironic that deep beneath St Peter’s Square in the heart of Manchester lies the Birley family crypt. Burrow beneath the streets where St Peter’s Church once stood and you will find the tombs where Hugh Hornby Birley was buried on 8 August 1845, just eight days before the 26th anniversary of Peterloo. By that time, it is doubtful that anyone congregated outside his mill or home, but the ghosts of St Peter’s Field could jeer at his corpse for an eternity.’

It is ironic that deep beneath St Peter’s Square in the heart of Manchester lies the Birley family crypt. Burrow beneath the streets where St Peter’s Church once stood and you will find the tombs where Hugh Hornby Birley was buried on 8 August 1845, just eight days before the 26th anniversary of Peterloo. By that time, it is doubtful that anyone congregated outside his mill or home, but the ghosts of St Peter’s Field could jeer at his corpse for an eternity.’

Jeff Kaye is the author of the forthcoming novel, All the People. It is a story of the fight for survival by Manchester people between the Reform Act of 1832 and the Plug Plot Riots of 1842, due for publication in the autumn of 2019. During the last 15 years, Jeff’s work within international Non-Government Organisation’s such as Global Witness and Transparency International added greatly to his interest in Britain’s development. All the People is the outcome. He previously wrote Last Line of Defense about corruption in America, following his earlier career in hi-tech industries. Jeff is a graduate of the University of Manchester.

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM.

A portrait of Hugh Hornby Birley is on display in PHM’s new exhibition Disrupt? Peterloo and Protest until Sunday 23 February 2020. The exhibition is part of PHM’s year long programme exploring the past, present and future of protest, marking 200 years since the Peterloo Massacre; a major event in Manchester’s history, and a defining moment for Britain’s democracy. The exhibition is supported by The National Lottery Heritage Fund.

People’s History Museum is open seven days a week from 10.00am to 5.00pm, and is free to enter with a suggested donation of £5. Radical Lates are the second Thursday each month, 10.00am to 8.00pm.