Here at PHM we’re commemorating 200 years since the Peterloo Massacre; a major event in Manchester’s history, and a defining moment for Britain’s democracy. We asked Katie Belshaw, Curator of Industrial Heritage down the road at Science and Industry Museum to provide some context about early 19th century Manchester’s expanding cotton industry.

‘Many thousands of cotton industry workers from Manchester and its surrounding towns were present at the immense but peaceful gathering which took place at St Peter’s Field on 16 August 1819, which culminated in the death of at least 18 people and the injury of around 700 hundred more, when mounted soldiers attacked the gathered crowds. That so many of the estimated 60,000 who assembled to hear Henry Hunt speak were employed in the cotton industry reflects the levels of disenfranchisement felt by the people whose labour was driving Manchester’s industrial transformation in the first decades of the 19th century.

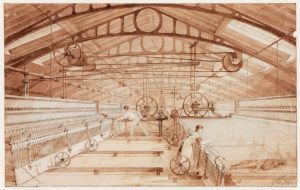

By 1819, Manchester’s cotton industry was booming. Huge, multi-storey, steam powered cotton spinning mills had arrived in the town, many clustered around the burgeoning industrial suburb of Ancoats, where thousands of mill workers lived cheek by jowl alongside the factories. New machine innovations and ambitious entrepreneurs who saw the profit-making potential of cotton spinning had transformed the processing of raw cotton into yarn in less than a generation. Manchester’s largest cotton employers were brothers Adam and George Murray of Ancoats, whose spinning mill employed over 1,200 people, and their neighbours James McConnel and John Kennedy, with over 1,000 workers. Mechanised cotton spinning had also taken hold in neighbouring communities like Ashton, Bury, Oldham and Stockport.

By 1819, Manchester’s cotton industry was booming. Huge, multi-storey, steam powered cotton spinning mills had arrived in the town, many clustered around the burgeoning industrial suburb of Ancoats, where thousands of mill workers lived cheek by jowl alongside the factories. New machine innovations and ambitious entrepreneurs who saw the profit-making potential of cotton spinning had transformed the processing of raw cotton into yarn in less than a generation. Manchester’s largest cotton employers were brothers Adam and George Murray of Ancoats, whose spinning mill employed over 1,200 people, and their neighbours James McConnel and John Kennedy, with over 1,000 workers. Mechanised cotton spinning had also taken hold in neighbouring communities like Ashton, Bury, Oldham and Stockport.

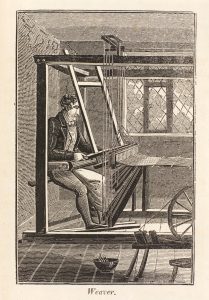

Meanwhile, the weaving of yarn into finished cloth remained largely a domestic industry, carried out on handlooms in homes or small workshops in Manchester and its surrounding towns. Powered looms were in development and gradually being adopted by manufacturers, but it was only in the proceeding decade that the technology advanced enough to produce results comparable to the cloth made by skilled handloom weavers, which finally resulted in the wholescale transfer of weaving from home to steam powered factory.

By the first decades of the 19th century, exports of cloth made in Manchester and its surrounding towns were flooding markets across the world and the cotton industry was providing work to almost one third of Lancashire’s population. Manchester started to attract the attention of visitors from far and wide, who came to witness its burgeoning industrial transformation. A swiss industrialist, Hans Escher, visiting Manchester in 1814, was impressed by the town’s new cotton mills, enthusing;

‘The spinning mills are now working until 8pm by (gas) light. Unless one has seen it for one’s self, it is impossible to imagine how grand is the sight of a big cotton mill when a façade of 256 windows is lit as if the brightest sunshine were streaming through the windows.’

The new cotton mills were the largest, most technologically advanced buildings of their day, entirely brick-built, gas-lit and powered by thunderous steam engines. Yet other witnesses painted a far less romantic picture of Manchester’s new factories. In 1818, an article in the radical publication Black Dwarf condemned the exhausting working hours enforced by cotton mill owners;

‘The workmen…are trained to work from six years old, from five in a morning to eight and nine at night… There they are…locked up until night… and allowed no time, except three-quarters of an hour for dinner in the whole day.’

Winter or summer, rain or shine, the factory bell summoned thousands of workers to the mills for gruelling days of up to 15 hours labour, six days a week. Many people also deplored the young age at which children were sent to work. Starting as young as six, they toiled for the same long hours as adults, working as scavengers, sweeping beneath fast-moving machinery, or as piecers, fixing broken threads on the spinning machines. Spinners were largely men, whilst women worked on winding machines, or in the carding room, preparing cotton for spinning. Common to almost all mill tasks was their dull and repetitive nature, organised around the monotonous rhythm of the factory machines. Mill discipline was maintained with a system of petty fines, punishments and forced dismissals.

Compounding the demanding hours of labour, harsh discipline and monotony of work, mill temperatures could reach unbearable highs and the humid air, thick with cotton dust, caused many workers breathing problems and lung disease. A surgeon, Dr Ward, who visited a Manchester cotton mill in 1819 reported that he ‘could not remain ten minutes in the factory without gasping for breath’. He was astonished at mill workers’ ability to bear the conditions for such long hours. Working amongst the roaring machines without protection, many workers also experienced hearing loss and with no guarding on the fast-moving machines, injuries, particularly to mills’ youngest workers, were all too common.

In the years leading up to Peterloo, thousands of Manchester’s mill workers petitioned employers for fairer wages, a reduction in working hours and the regulation of child labour. In the summer of 1818, striking spinners picketed cotton mills, attacking what they saw as the tyrannical and oppressive capitalism of mill owners. They argued that their average wage had dropped from 24 shillings a week in 1815 to 18 shillings in 1818. One target of the 1818 action was the cotton mill of Hugh Hornby Birley, Captain of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry, who would go on to lead the charge into the crowds at Peterloo. Known for his particularly harsh treatment of workers, 200 strikers surrounded Birley’s factory and threw stones.

Thousands of handloom weavers shared the discontent of factory spinners, mounting their own strikes in response to falling wages. They were particularly concerned about the gradual adoption of powered looms, which they predicted would replace their skills and take away their livelihoods. Evidence of wages prepared for the prosecution at the trials following Peterloo showed that some handloom weavers were earning just six shillings a week in 1819. When a pound each of butter, cheese, potatoes, onions and mutton cost almost four shillings, it is not surprising that many handloom weavers subsisted on a meagre diet of potatoes or oatmeal mixed with salt.

In 1819, then, the workers driving forward Manchester’s industrial transformation were bitterly disillusioned. Whilst capitalist manufacturers reaped the rewards of the cotton industry, the men and women who sustained their profits felt oppressed and unrepresented. Angry at their inability to make themselves heard, they gathered in their thousands on 16 August at St Peter’s Field, to demand a voice.’

Katie Belshaw is Curator of Industrial Heritage at Science and Industry Museum.

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM.

PHM’s exhibition Disrupt? Peterloo and Protest is on show until Sunday 23 February 2020. The exhibition is part of PHM’s year long programme exploring the past, present and future of protest, marking 200 years since the Peterloo Massacre; a major event in Manchester’s history, and a defining moment for Britain’s democracy. The exhibition is supported by The National Lottery Heritage Fund.

People’s History Museum is open seven days a week from 10.00am to 5.00pm, and is free to enter with a suggested donation of £5. Radical Lates are the second Thursday each month, 10.00am to 8.00pm.