All year PHM is marking 200 years since the Peterloo Massacre; a defining moment for Britain’s democracy. For Bastille Day we asked Dr Jonathan Spangler, Senior Lecturer in Early Modern European History at Manchester Metropolitan University to describe how political activity on one side of the Channel certainly influenced outcomes on the other in August 1819.

‘In the aftermath of the Peterloo Massacre on 16 August 1819, Britain’s political parties faced each other in parliament to debate how best to react to the violence in Manchester and the demands for political reform. Both sides of the debate referred to events of the French Revolution, still fresh in living memory, to make their cases for either swift reform or assertive crackdown. One side saw the events in France in 1789 as opening up a more just society, with government answerable to all of its citizens; while the other saw the outbreak of popular revolt as the unleashing of chaos and violence which did nothing but harm to the wellbeing of the populace.

It is interesting that both sides of the debate made use of the disruption of the French government to argue for opposite actions. And political leaders in Lord Liverpool’s government at the time were right to be wary of a relatively small skirmish in Manchester, as events on a similar scale elsewhere observably led to much bigger events. A skirmish on 12 July 1789 in the Tuileries Gardens in Paris led to the more famous events on 14 July, and within weeks, the collapse of the Old Regime in France. These events were influenced by a small popular reaction against government oppression that had happened across the Atlantic Ocean, in Boston, in March 1770. In all three cases, Boston, Paris and Manchester, the importance of the press in spreading the news was crucial.

The Boston Massacre on 5 March 1770 was the culmination of several years of protest by English colonists in British North America; a reaction to the increasing burden of taxation imposed by the government in London, and tariffs on items manufactured in Britain and shipped to the colonies. However, without a representative voice in parliament, the colonists were unable to voice their dissent except through public protest. The Crown responded by sending troops to Boston, as the location of the headquarters of the new American Customs Board, to protect government officials and enforce the new laws. In February 1770, tensions peaked at the public funeral of an 11 year old boy who had been killed by a Customs employee. On 5 March, a crowd gathered in front of the Customs House, taunting the soldiers guarding it. One of the soldiers shot into the crowd, and soon three protestors were dead, two mortally wounded and six others shot. The Crown’s troops were immediately withdrawn from the city and the colony’s governor promised an enquiry. Eight soldiers, one officer and four civilians were arrested; only two of the soldiers were convicted of manslaughter (not murder) and were given a reduced sentence (branding).

Parliament in London was already in the process of repealing many of the hated taxes (except for the one on tea, with famous consequences), and troops were fully withdrawn from Boston by May 1770. However, the publication of accounts of the massacre in the Boston Gazette soon circulated throughout the thirteen colonies.

An engraving of the events by silversmith Paul Revere, a well known leader of colonial protest, stood out. Following the larger protest against taxation without representation known as the Boston Tea Party (December 1773), protest escalated into violence with skirmishes between the local militias and British troops at the nearby villages of Lexington and Concord (April 1775), a shocking Declaration of Independence (July 1776), and all out war.

From December 1776, one of the leaders of this rebellion, Benjamin Franklin from Philadelphia, took American interests to France. Parisian salons were keen to learn of the latest developments in the expressions of liberty which had been so ardently cultivated in France. Several aristocrats notably the young Marquis de Lafayette, travelled to America to help. Lafayette became essentially the adopted son of the childless American Commander-in-Chief, George Washington.

Just over a decade later, back in Paris, Lafayette was called on to restore order following a popular revolt against perceived government tyranny. As with Boston, the larger protest was sparked by a smaller, mostly forgotten skirmish, in the gardens of the Tuileries Palace on 12 July 1789. As with the American colonists, the demands of the people of France in spring 1789 were not initially to overthrow the royal government, but to reform it. Most people were fiercely loyal to their monarchy.

But the government was unable to function, due to a complete financial collapse, and an inability to pass reform measures in the Estates General. The King, Louis XVI, called this body to meet to hear the complaints and suggestions of delegates from all over France; but one fundamental question prevented them from even starting debate, the idea of whether the three estates (the clergy, the nobility and the commons) should vote by order (one each, as was traditional), or by head. The latter would mean that the Third Estate (the commons) would dominate any vote, overwhelmingly. On 17 June, the Third Estate proclaimed itself the National Assembly. The King tried to prevent them from meeting, so they found a large room in which tennis was played and swore an oath never to separate until a new constitution had been written for France.

In the midst of this political upheaval, France was also suffering from food shortages and skyrocketing prices. To try to maintain order Louis XVI ordered troops to Paris on 22 June and tried to get the Estates General to meet as before. This prompted the famous line by a leader of the newly self-proclaimed National Assembly, the Comte de Mirabeau, ‘We are here by the will of the people, and won’t leave but by the force of bayonets’. Two tense weeks passed, and on 11 July, the Minister of Finance, Jacques Necker, the man seen by the majority of reformers and the Parisian crowds as the person who could fix the government’s financial meltdown, resigned. Parisians took to the streets, angry that the King would not support Necker’s plans for fiscal reforms, and at his calling in troops to surround their city.

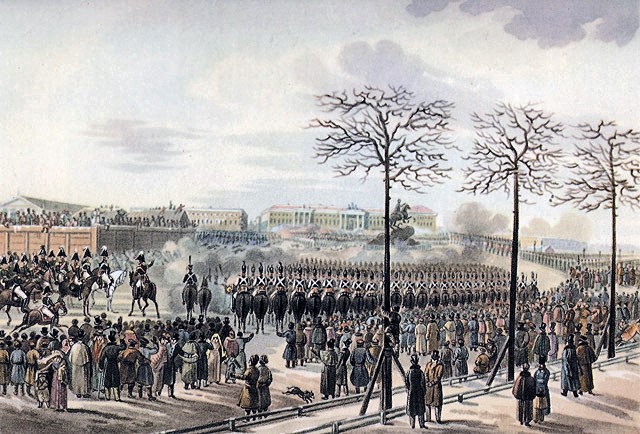

The Prince of Lambesc, Charles-Eugène de Lorraine, was commander of a regiment of cavalry from the eastern part of France (the Royal Allemand), where many people spoke German. On 12 July, the Military Commander of Paris ordered Lambesc to take his troops into the city and to clear a huge crowd from the gardens in front of the Tuileries Palace (located directly opposite the Louvre). Trained for battle tactics, not crowd control, Lambesc and his soldiers clumsily set about the crowd with the flats of their swords. Some in the crowd threw bottles and chairs at the soldiers, and the violence escalated when soldiers from the Gardes Françaises, the King’s own personal guard, some of whom were now in sympathy with the protestors, fought hand to hand with the dragoons from the Royal Allemand, whom many considered to be foreigners and the enemy of true patriots. Several people were injured, at least one person killed, and by the following day, the streets were filled with protesters. An ad hoc militia was formed to protect the people of Paris from the violence of their own government, and, in need of guns and ammunition, on 14 July, they took control of the main supply store in Paris, the Bastille fortress-prison. The King ordered the royal troops to withdraw, and agreed to the conversion of the French Guard into the National Guard, with Lafayette as their commander. He recalled Necker and travelled to Paris to acknowledge the start of the new order. But it was too late: as with the Boston Massacre of 1770, the cavalry charge at the Tuileries was quickly immortalised in prints which were distributed across the country and enflamed the nation.

Through the print above, and accounts in various newspapers across France, rather than restoring order, the King was seen to have attacked his own people. In October 1789, he was brought by force from Versailles to Paris, to be more directly accountable to the people for his decisions in government. After two years of attempts to forge a constitutional monarchy (along the lines of the British system), he was removed as head of state in September 1792, and executed the following January. Another republican experiment, like that in North America, was set to begin.

These events were in the minds of members of parliament in London in 1819. They would have remembered that the swift repression of popular protest in Boston and in Paris had not led to restored order, but to increased violence, and years of warfare. The impact of the French Revolution on Britain was finally brought to an end in 1815, with Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo. But the government of Lord Liverpool, who intriguingly had been present in Paris in July 1789, was not alone in its desire to keep slow reform from turning into revolution. It is important to see the events of Peterloo in the context of wider movements across Europe. In France, the recently restored monarchy had agreed to the Charte, a constitution limiting the power of the King, but conservatives bristled against it until it was virtually suspended under King Charles X, leading to his removal in the Second Revolution in July 1830. Other events contemporary to Peterloo demonstrate similar calls for political reforms: in Spain, the Revolt of the Cabezas de San Juan in January 1820 forced King Ferdinand VII to accept a constitution, and similar events transpired in Italy during the revolt of the Carbonari in Naples and Turin. In contrast, the Carlsbad Decrees by the Emperor Francis I in 1818 put a stop to reform movements all over Germany and the Austrian Empire. Further east, the Decembrist Revolt in Saint Petersburg in 1825 was led by 3,000 soldiers and civilians demanding a constitution and an end to serfdom, and was brutally put down by the Tsar’s cavalry and artillery. Some estimates say as many as 1,000 people were killed.

It is against this background of several decades of revolt, reform and repression that the reactions of the British establishment to the violence in St Peter’s Field, Manchester on 16 August 1819 should be viewed. The immediate action was the gagging of local newspapers and the forbidding of large public meetings. But in the longer term, public desire for genuine reform was too strong, and by the 1830s, a decade of peaceful reform emerged and Britain avoided the violent upheavals that shook most of the rest of Europe in the turbulent year of 1848. Indeed, the repeal in 1846 of the Corn Laws, the major motivation behind the Peterloo protests, allowed for a more peaceful petition for further reform by the Chartist movement to parliament in April 1848. But that is another anniversary year…’

Dr Jonathan Spangler, Senior Lecturer in Early Modern European History at Manchester Metropolitan University

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM.

Disrupt? Peterloo and Protest exhibition is at PHM until Sunday 23 February 2020 as part of PHM’s year long programme exploring the past, present and future of protest, marking 200 years since the Peterloo Massacre; a major event in Manchester’s history, and a defining moment for Britain’s democracy.

People’s History Museum is open seven days a week from 10.00am to 5.00pm, and is free to enter with a suggested donation of £5. Radical Lates are the second Thursday each month, 10.00am to 8.00pm.