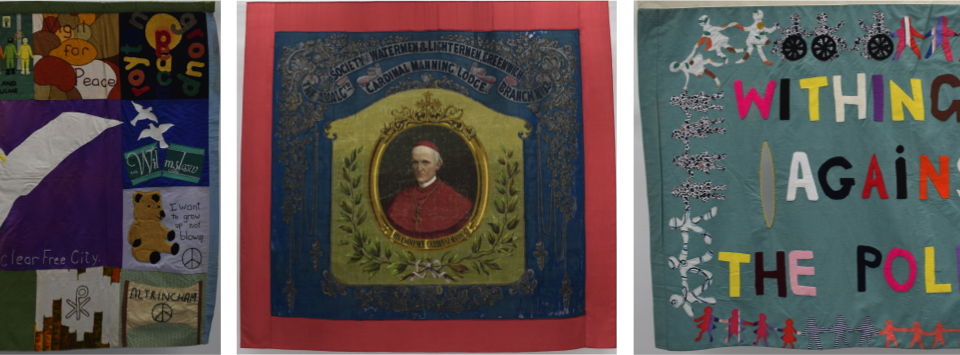

PHM’s 2019 banner display has been carefully curated to reflect key moments of protest in Greater Manchester and across Britain, representing a mix of creatively disobedient ideas and actions along the road to democratic reform, from the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester in 1819 to today.

We asked historian Peter Morgan, who’s also head writer for our friends at The Radical Tea Towel Company, to review our new display of banners.

‘When our calendars reach 16 August this year, it will be 200 years to the day that the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry – ‘the local business mafia on horseback’[1] – began the Peterloo Massacre.

Sabres drawn, they charged the gathering crowd of 60,000, unarmed, and working class people on St Peter’s Field in Manchester (now the area around St Peter’s Square) as they met peacefully to call for the right to vote, for freedom from oppression and for justice.

But the yeomanry’s rampage, quickly joined by regular units like the 15th Hussars, was not wholly aimless. They were after the banners which had been brought to the meeting. The only surviving banner belonged to Thomas Redford, a Peterloo participant from Middleton. The banner reads ‘Liberty and Fraternity’ on one side, and ‘Unity and Strength’ on the other.

Inscribed with these kind of rhetorical traces from the French Revolution and other such sources, the banners held on St Peter’s Field in 1819 embodied the bold, democratic radicalism of that gathering in a material form. This is why they were targeted. The ‘younger members of the Tory party in arms’[2] who made up the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry wanted to steal these banners so as to rip the symbolic heart out of their working class enemy.

This theft and destruction of the radical banners at Peterloo, then, is proof of how important they have been as tools of protest and dissent in British history. And while Thomas Redford’s is not part of the new display of banners at the People’s History Museum (PHM) the cultural spirit of Peterloo animates the entire display. As the curator, PHM Programme Officer Michael Powell, assured me, the new display’s organising themes of youth, Greater Manchester, and the creativity of civil disobedience all have a base in the experience of Peterloo.

My own engagement with the cultural field of our radical past has mainly been with its literature – historical monographs like E P Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class, pamphlets such as Tom Paine’s Common Sense, diaries like those of the late Tony Benn etc (PHM’s Labour History Archive & Study Centre contains correspondence of both Tony Benn’s and E P Thompson’s on a variety of subjects). And, like many focused on the literary, I have come to suffer from the philistine prejudice that literature is somehow more complex than other forms of expression.

For me, the new display of historic and contemporary banners at the PHM has forced some important steps away from this narrow-mindedness – no assumption that banners, as primarily visual objects, provide something relatively straightforward can outlast a tour through this display.

From the first to the last (there are 26 in total), a close viewing of these expertly conserved banners, aided by the contexts provided, makes clear the sheer range of functions which banners can perform and the sophistication with which they have been made to perform them. Take, for example, two of the banners toward the end of Main Gallery Two, made in the 1890s by different branches of the Dockers’ Union formed in the wake of the Great London Dock Strike of 1889 (for which the famous socialist hymn, The Red Flag, was written).

Both stunning works of design, the one made by the Ipswich Branch shows on one side two labourers perched on barrels of trade goods in a dockyard with a merchant ship sailing in out of the distance, to emphasise the value of the dockers’ work to Britain’s commercial wealth. On the reverse of the banner stands a docker and his employer shaking hands, with an angel above them holding the words, ‘MAY THEY EVER BE UNITED’.

In stark contrast, hanging nearby, is the banner made by the Dockers’ Union Export Branch of the same union. Centred here is not an image of harmony, but one of bitter conflict – a depiction of Hercules grappling with a serpent and framed by the slogans, ‘WE WILL FIGHT AND MAY DIE BUT WE WILL NEVER SURRENDER’ to its right, and ‘THIS IS A HOLY WAR AND WE SHALL NOT CEASE UNTIL ALL DESTITUTION, PROSTITUTION & EXPLOITATION IS SWEPT AWAY’ beneath it.

The difference between these two Dockers’ Union banners wasn’t, I’d wager, a matter of aesthetic preference, but one of political philosophy. The Ipswich Branch design holds up the ideal of harmony between employers and employees (‘may they ever be united’) and promotes negotiation and agreement as the means to realise it (with the handshake). The Export Branch banner, on the other hand, presents industrial relations as a (literally) Herculean struggle of labour against exploitation – a ‘Holy War’ in which the dockers ‘will fight’ and ‘may die’. The road to success being advocated here was not negotiation, (the serpent that Hercules is wrestling has no hand to shake) but battle i.e. the strike.

Physically juxtaposed with each other by the display, these two trade union banners make us consider how they were not mere ‘decorations’ but also arguments being made – through a genius combination of image and word – by workers on either side of the late 19th century debate about methods in the British labour movement.

A tribute to and from Peterloo

This quick reflection on the dockers doesn’t exhaust the variety of radical functions which the new display shows banners performing over the decades. Far from it. For example, the banner in the middle of Main Gallery One made by Russian textile workers and dedicated to the textile workers of Yorkshire in the 1920s can be seen as a type of ‘diplomatic communique’, in an attempt to build up working class support in the West at a time when the young Soviet Union faced civil war and foreign invasion. Michael Powell also raised the notion that outside of the final product, the collective process of making a banner can also serve as a forum for valuable political discussion and development among those who would later march under it.

For me, then, the unlimited-ness of what a banner can do for radical politics is a central and valuable takeaway from PHM’s 2019 Banner Display. In its political sophistication as well as its artistic beauty, this new display of banners at PHM is a really well made testament to the often under-appreciated – not least by me(!) – genius of banners as objects of progressive thought and expression.

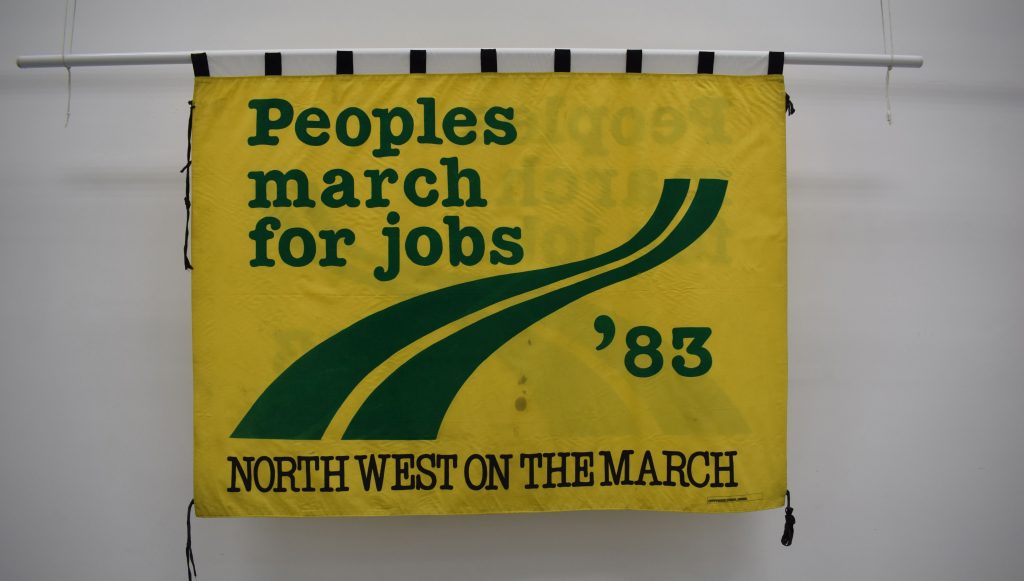

These banners, displaying the creativity-in-communication which has defined Britain’s modern radical tradition, make for a fitting tribute to Peterloo at the beginning of its bicentenary. They also, in a way, together add up to Peterloo’s tribute to us. As Michael told me, many of the practices of protest which these banners incorporate were inaugurated by the activists at Peterloo in 1819 – not least the tactic of marching and carrying banners itself, best seen in his personal favourite, the 1983 Peoples March for Jobs banner.

It’s not just Thomas Redford’s ‘Liberty and Fraternity’ banner (at Touchstones, Rochdale) that survives 1819, then – each of the 26 banners on display at People’s History Museum, from those made in the 1890s to the ‘Nothing About Us Without Us’ disability rights banner made in 2015, is in a way part of our inheritance from Peterloo.’

[1] Krantz, Mark (2011), Rise Like Lions: The History and Lessons of the Peterloo Massacre of 1819 (page 12)

[2] Wainwright, Martin (13 August 2007), Battle for the memory of Peterloo: Campaigners demand fitting tribute

Historian Peter Morgan is the Head Writer at The Radical Tea Towel Company.

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM.

Until Sunday 5 January 2020

The majority of banners on display at PHM change annually, revamping a quarter of the museum’s main galleries. Visit 2019’s selection of historic and contemporary banners – some on public display for the first time, all specially conserved by the museum’s expert Conservation Team.

In the museum shop we stock The Radical Tea Towel Company tea towels and Mark Krantz’s, Rise Like Lions: The History and Lessons of the Peterloo Massacre of 1819 (£3). This pamphlet has recently been republished by Bookmarks publishers – an accessible and exciting way into this history.