2025 marks the 80th anniversary of the fifth Pan-African Congress, which took place in Manchester (15 – 21 October 1945). Historian Geoff Brown and PHM and Manchester Metropolitan University researcher Dr Shirin Hirsch look at a document on display in the museum’s galleries in a blog about the role of black activists in Manchester in the build up to the Congress.

Save your place to join us for an archival exploration to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the 1945 Pan-African Congress on Friday 17 October 2025 at 5.00pm. You can also join a waitlist for tickets for a lecture at 7.00pm with award-winning author, broadcaster and academic Professor Gary Younge discussing this global moment in Manchester.

The fifth Pan-African Congress, which took place in Manchester from 15 to 21 October 1945, was a watershed moment in world history; arguably one of the most important events to take place in Manchester in the 20th century. It is an event we celebrate at People’s History Museum (PHM) as part of our local, national and global history of democracy. The Congress held 200 attendants with 87 delegates representing 50 organisations from across the world. Many delegates would return to Africa newly inspired as part of a network of Pan-Africanists. Jomo Kenyatta, Kwame Nkrumah and Dr Hastings Banda were key delegates at the Manchester Congress and went on to lead anti-colonial movements against Britain, becoming the first leaders of the independent nations of Kenya, Ghana and Malawi respectively. The Nigerian delegates included the future finance minister, Obafemi Awolowo, future foreign minister, Jaja Wachuku, and future federal minister, H O Davies. The Congress gave agency to African people in the remaking of the modern world and the struggle for decolonisation.

The fifth Congress met in Chorlton-on-Medlock Town Hall, the original entrance of which is now part of Manchester Metropolitan University’s Arts and Humanities building. Previous Pan-African Congresses had been held in Paris, Brussels, Lisbon, London and New York, but the Congress in Manchester was the most important; taking place just after the end of World War II, with the weakening of colonial powers and the development and confidence of the feeling of colonial subjects that independence must become a reality. As the longstanding organiser of past Congresses and black intellectual W E B Du Bois argued, the fifth Pan-African Congress made 1945 a ‘decisive year in determining the freedom of Africa’. In the Picture Post magazine report entitled ‘Africa speaks in Manchester’, the journalist explained that Manchester was chosen as the site of this Congress because ‘its people have less curiosity or hostility towards colour than the people of any other English city’. Another article in the Manchester Guardian, however, quoted a delegate from Jamaica, Miss Alma La Badie, who found the people of Britain ‘not unkind, but entirely ignorant of the conditions under which people live in the lands where their flag is flown – disgusting conditions which would surely appal them if they knew’. Dr Peter M Milliard of Manchester, president of the Pan-African Federation, in introducing the Lord Mayor to speak at the Congress, said that those who had lived here must agree that Manchester was probably the most liberal city in England. More importantly though, after first Paris and then London had been proposed, with the deadline approaching, it became clear that the Congress had to be held in Manchester, the strongest centre of Pan-African organisation in Britain.

There were rich black networks in Manchester that existed prior to the Windrush generation. One of the key Pan-Africanists during the war years was Ras T Makonnen, who was central to the Congress taking place in Manchester. Makonnen was born in British Guiana, and as he became more involved in the Ethiopian cause following the Italian invasion in 1935 he took the name Ras Tefaris Makonnen. He studied in America and Denmark and came to London in early 1937 where he shared a flat in London with the Pan-African leader George Padmore. During the war Makonnen left London when, with the onset of the Blitz, a lot of the Pan-Africanists decided to disperse across the country to avoid conscription and retaliation by the state. They had refused to be recruited to the war effort, with their key focus not on supporting Britain but in opposing colonial Britain and all it stood for – ‘We are only concerned about the man who is on our shoulders now’ as Makonnen put it. Makonnen chose Manchester as his new destination because Dr Peter Milliard was already here and he was able to ‘room with him for a time’.

Milliard, also born in British Guiana, trained to be a doctor at the black Howard University in Washington DC. During World War I he worked as a medic in Panama where he helped lead a canal workers’ strike. He settled in Manchester, establishing a general practice in Lower Broughton which became an important support centre for black seafarers arriving at the nearby Salford docks. Milliard founded the International Brotherhood of Ethiopia in Manchester opposing the 1935 Italian invasion of Ethiopia, organising and speaking at street meetings in Stevenson Square in central Manchester.

When he first arrived in Manchester, Makonnen lectured at the Co-operative College in Holyoake House, Hanover Street. Seeing the need to provide spaces free of ‘colour bars’ for Manchester’s black communities, he set up a chain of restaurants along the top of Oxford Road. These included the Ethiopian Teashop, the Cosmopolitan, the Orient, a club called the Forum and a place called Belle Etoile. He went on to open a bookshop and founded a publishing house producing a stream of pamphlets and the excellent monthly magazine Pan-Africa. The restaurants were hugely successful, attracting black seafarers, West Indian servicemen and African workers based in Greater Manchester. The venues were wildly popular with black American GIs from the giant US airbase at Burtonwood near Warrington which, like all US armed forces at the time, was segregated. For a time Jomo Kenyatta, future president of Kenya, managed the Cosmopolitan, and Kath Locke, Moss Side community activist and co-founder in the 1970s of the black women’s Abasindi Co-operative, worked there. Through the profits Makonnen made he was able to help finance the hosting of the fifth Pan-African Congress and at a time of the ‘colour bar’ when accommodation was difficult, provide spaces for black delegates. His links to the Lord Mayor of Manchester and the Labour Party, who had political control of the city at the time, also meant the securing of the large Chorlton-on-Medlock Town Hall as the venue for the Congress.

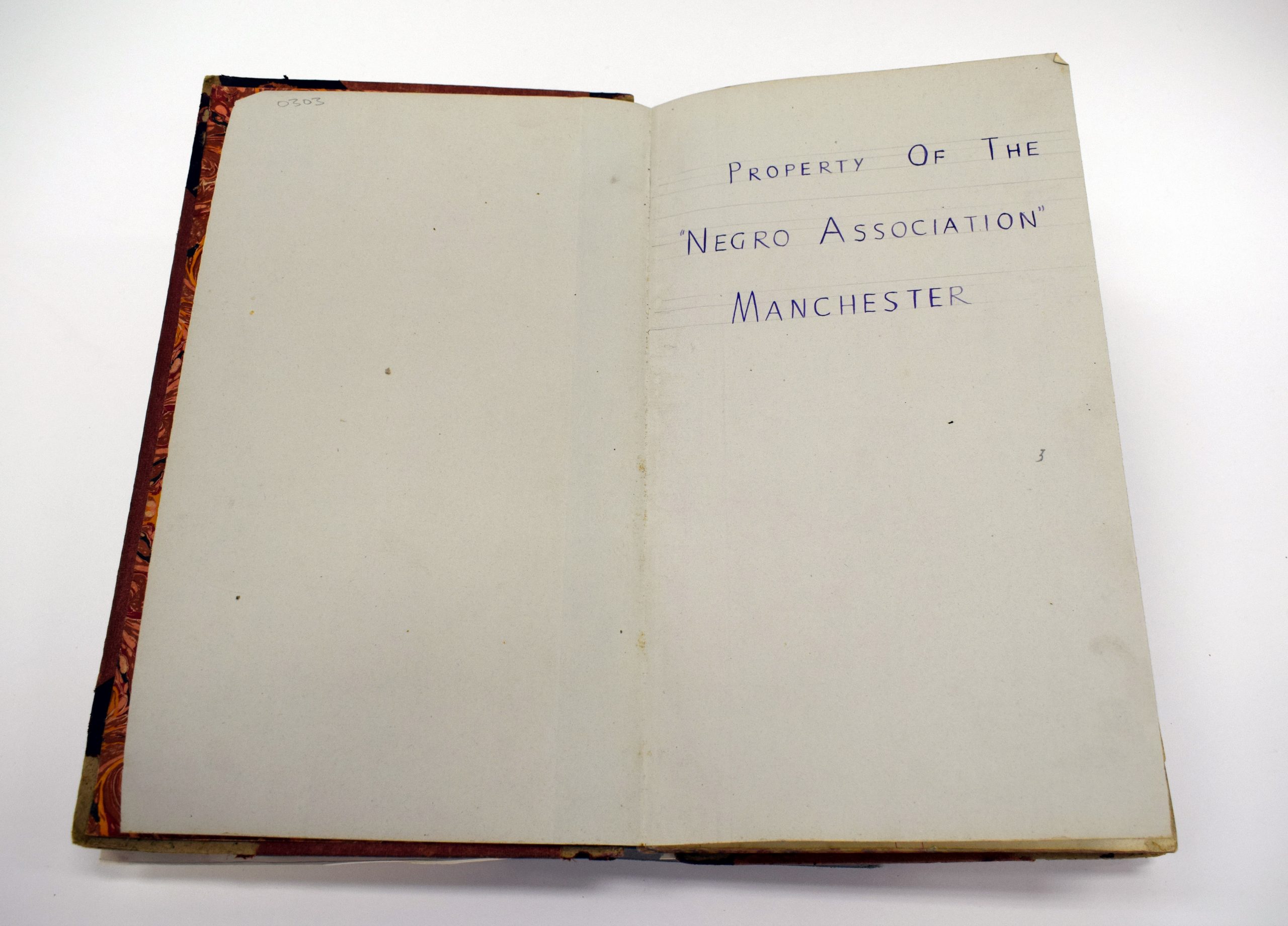

PHM’s collections show this rich black history that existed in Manchester. With a peak membership of 500, The Negro Association, Manchester was a key network, established in 1943 by Peter Milliard, providing the basis for the Manchester branch of the Pan-African Federation founded in 1945. The association actively encouraged solidarity with anti colonial struggles, for example raising money in support of the great Nigerian general strike in the summer of 1945. The document pictured above (on display in Main Gallery Two) shows the names and addresses of members of The Negro Association in Manchester. We can see their names, not through the patronising and racist reporting at the time, but through the handwriting most likely of Milliard himself. There is plenty more research to be done on the lives of those on the membership list; some are famous, like Kenyatta, but others we know little about. The membership list, in demonstrating black self-organisation and agency within Manchester, stands in contrast to the Picture Post article we started this blog with, where the Congress is veiled through the words of the condescending journalist noting the ‘positive side of our rule in Africa’ and patronisingly commenting that ‘hothead’ delegates of the Congress held ‘extremist’ views. It is hard, from these media reports, to get a sense of the exhilaration and sense of freedom that black people must have felt meeting and organising in Manchester. Walking into the Town Hall for the Congress, with the flags of black independent nations on display, there must have been a feeling of pride and determination to continue the struggle in Africa against colonial rule and in opposing the ‘colour bar’ in Britain. For those who had previously organised in Manchester, the Congress must have been particularly inspiring, taking a leading role in the process of self-emancipation from colonialism and racism. We will leave the last words to Mr Richardson (seen on the membership list as Richinson) of Manchester, a delegate of the Congress. He had lived in England for 45 years and explained to the reporter that he intended to stay ‘to help civilise the English people’. We remain indebted for such actions.

At PHM we are continually building on the collection, and we would love to add more to represent the history of migrants and BAME (black, Asian and minority ethnic) communities in Britain over the last 200 years. If you have any objects or archives you think would be an important addition to the museum’s collection, please email collections@phm.org.uk. Find out more about PHM’s collection.

Historian Geoff Brown was active in the Vietnam Solidarity campaign and member of the Revolutionary Socialist Students Federation in the late 1960s and an Anti Nazi League Manchester organiser; helping to organise the Northern Carnival against the Nazis in Manchester, July 1978. Union tutor from 1979 working with shop stewards, union secretary until he was victimised after which he became an official for his union, University and College Union (UCU). Now working as a historian. His recent publications include John Tocher and the limits of commitment, North West Labour History, 2018 and Not just Peterloo – The Anti-Apartheid march to the Springbok match, Old Trafford, Socialist History, Autumn 2019.

Dr Shirin Hirsch is a historian and Lecturer in History at Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU). She specialises in the history of modern Britain with a particular focus on the labour movement, as well as questions of race and Empire.

Find out about the life of Thomas Bangbala, who attended the Fifth Pan African Congress, in a previous blog from Dr Shirin Hirsch.

Join the Ahmed Iqbal Ullah Race Centre, North West Film Archive, Manchester Metropolitan University, PHM and the Working Class Movement Library at PHM on Friday 17 October 2025 for an evening of archival exploration: Archives in Solidarity

Book tickets for our speaker event following the archive showcase. 80 years on you are invited to join award-winning author, broadcaster and academic Gary Younge as he discusses this global moment in Manchester with an insightful lecture and Q&A for Black History Month: What Peace? Whose Freedom? with Gary Younge.

An earlier version of this blog was published on 15 October 2020 and 1 June 2025.

People’s History Museum is the national museum of democracy in Manchester. Visit the museum website’s home page to find out more.