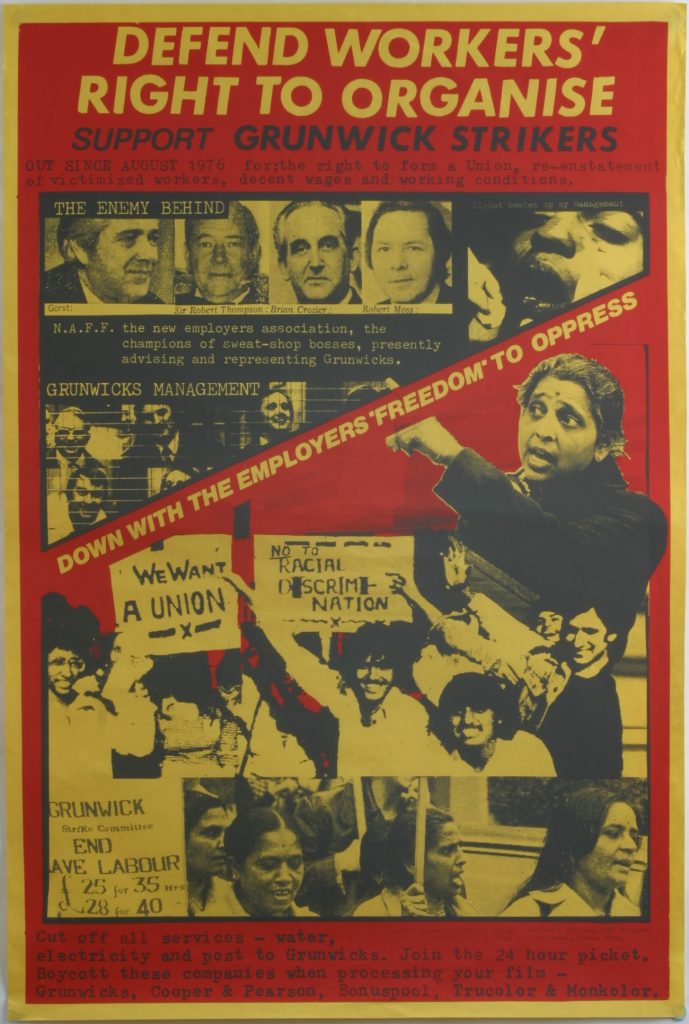

Earlier this month we shared a blog post that put the spotlight on a Grunwick strike (1976-1978) poster from People’s History Museum’s (PHM) collection and looked at its relevance today. Here PHM’s Researcher Dr Shirin Hirsch takes a closer look at the history of migrant workers documented in the museum’s collection.

‘…the outside history that is inside the history of the English.’

As Stuart Hall, the great black sociologist, once put it there was no English history without that ‘other’ history. Migrants were not simply newly injected into the country when the Windrush ship docked on Tilbury Docks in 1948 but instead were integral to the internal dynamics of British society over a much longer period. Even for those who did not migrate, the labour power of colonial workers had long entered the economic blood stream of Britain. This history has been repressed, yet the current pandemic has, through crisis, exposed the mobile and unequal fibres of our society as part of a much longer history of colonialism and racism. Within this, the key role of migrant workers is revealed, transformed from ‘unskilled’ to ‘essential’ workers.

This year at PHM we are rethinking how we see this global British history through our programme theme exploring migration, which includes our Community Programme Team planning a series of ‘interventions’ into our main gallery spaces. The museum’s collection holds many documents and objects that tell the stories of workers from our past. Some of these workers were born in the area in which they worked, some moved from countryside to city while others crossed national borders and even oceans. Working class histories are deeply connected with global networks of people in perpetual motion. The museum’s collection reflects this movement, weaving stories of Empire, race and migration into the democratic struggles of working people, past and present. Here I want to briefly showcase a few items from the collection that tell a collective and mobile story of work and resistance.

The trade union banners in the collection show some of these chains binding the fate of workers from the colonies to Britain. Through rich decoration and symbols, the banners offer clues to many of the political ideas within the British labour movement. The rise of trade union banners produced by professional banner makers like George Tutill came about at a time when a particular type of skilled, respectable trade union had moved into the open and were beginning to be taken seriously by the British state with the wave of New Model Unions in the 1850s. The banners commissioned reflected this newfound relative wealth and organisation with displays of strong union men protecting women from harm, decorated in patriotic Union Jacks. This was also a period in which the British Empire was reaping the wealth of its colonies under Queen Victoria, and an attachment to the Empire is sometimes visibly expressed through these banners.

You can see the threads of Empire in this Dockers Union banner, where trade with the British Empire is shown as central to the union, with the elephant representing British India next to the docker. This was a union formed out of the New Union period of the late 1800s, a trade union movement that rejected the elitism of past unions, yet the relationship to Empire is still complicated with colonial wealth flowing through the docks. The dockers were often described as ‘unskilled’ and, like the match girls who had sparked the New Union strike wave, were often from Irish backgrounds. In this period such Irish workers were racialised as savage and criminal elements of the working class, and their central involvement in the union shows the tensions in any idea of a ‘white’ working class movement. Race and the framing of ‘unskilled’ labour forcefully coalesced.

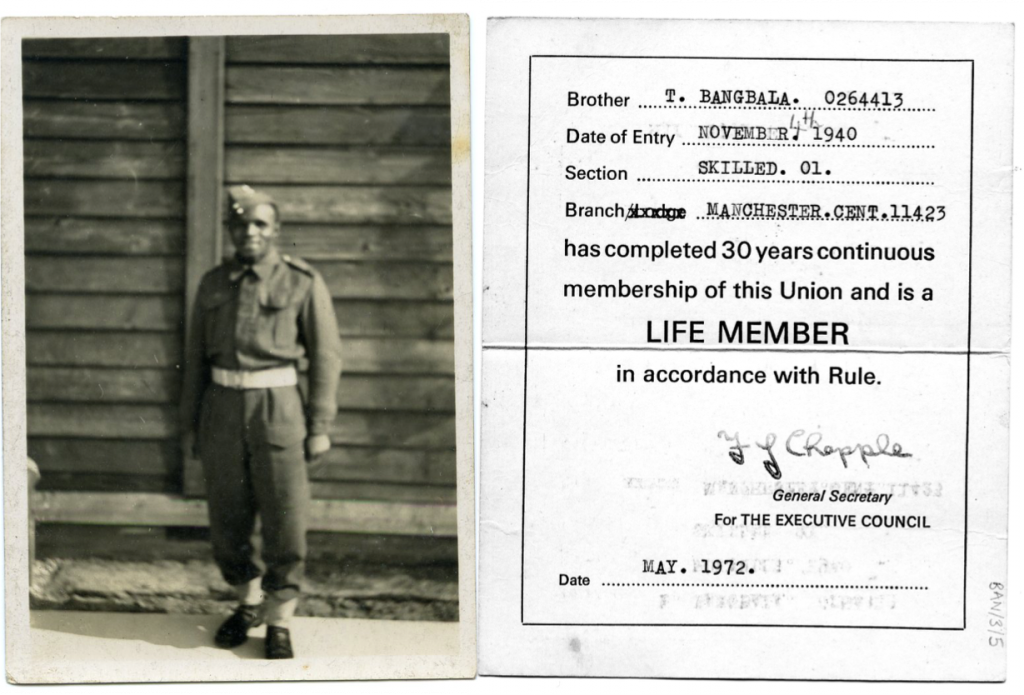

By the 20th century there were growing communities of sailors, slaves and pirates, the ‘motley crew’ at sea, that were now beginning to settle in port cities and towns in Britain. They built on earlier histories of black workers in Britain, like the tailor and Chartist leader William Cuffay, and the cabinet maker and radical William Davidson. The museum tells these histories within the museum’s collection, and in the archive we are lucky to hold a recently acquired collection documenting the life of the black engineer Thomas Bangbala. He was born in Nigeria in 1907 and at the age of 17 travelled to Liverpool as a Seaman. A few years later he began to study as an electrical engineer and moved to Manchester in 1928. In 1940 Bangbala joined the Electrical Trade Union, becoming the first black man to join the Manchester branch. He was an active Labour Party member and a campaigner against racism, attendee at the hugely significant fifth Pan African Congress of 1945 held in Manchester. Bangbala’s life as an engineer was not separate to, but integrated into his political activism in Manchester.

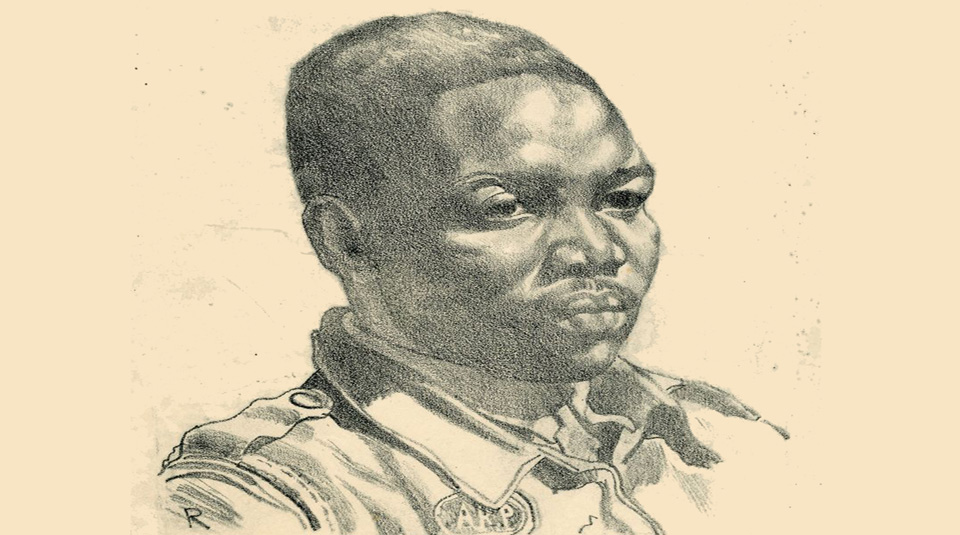

Although we have few of these individual personal collections, there are still traces of black workers in British society, like the main image, a print by the communist artist Cliff Rowe of a black Air Raid Precautions (ARP) warden during World War II. He looks serious and proud in his official wartime uniform, but we don’t know his name and can only imagine his role within the war and his life in Britain.

After the war, those from the Commonwealth were encouraged to Britain to help rebuild the country. ‘Welcome Home!’ read the Evening Standard headline on the arrival of the Windrush ship in 1948, the newspaper greeting the ‘400 sons of Empire’. Colonial subjects were integral to the rebuilding of British society, but they were not simply subservient or passive workers. Unlike Thomas Bangbala, who was allowed to join the union partly because of his active role with the local Labour Party, many black workers were excluded from trade union organisation and there were often separate strikes of black and white workers in the same workplace in the post war years. The Grunwick strike, however, challenged these divisions; a failed strike in its immediate demands, but one in which migrant workers, those who had often migrated not once but twice, from India to East Africa, to West London, were leading the way in trade union struggle between 1976 and 1978. These workers brought with them radical ways of organising and challenged racist divisions that had far too often determined the trade union movement.

Rather than detaching these histories of migrant workers as a separate other, the museum’s collection shows the ongoing role of migrants within working class struggle, and in the making and remaking of British society. These struggles continue today, illuminated through the life of Belly Mujinga. Mujinga was born in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and migrated to Britain in 2000. She was a railway ticket officer in London, refused personal protective equipment (PPE) by her employers, and spat at while on duty at work before falling ill and finally dying of coronavirus on 5 April 2020. Her family have yet to receive any form of justice, with British Transport Police (BTP) initially stating no further action would be taken. Mujinga’s tragic death points to the disposable ways in which such workers are treated by the British state. PHM’s collection points to a different way of viewing black and migrant workers, removed from narrow nationalistic frameworks, and instead understood as essential to who we are within a moving and connected world.

At PHM we are continually building on the collection, and we would love to add more to represent the work of migrants and BAME (Black, Asian and minority ethnic) history over the last 200 years. If you have any objects or archives you think would be an important addition to the museum’s collection, please email collections@phm.org.uk.

If you’d like to find out more about migration at PHM join a virtual tour of the museum, as we share the stories of those seeking sanctuary told through PHM’s galleries and collection on Friday 19 June at 11.00am on Twitter @PHMMcr and Instagram @phmmcr. Part of Refugee Week’s (15-21 June) ‘Simple Acts’. For Refugee Week we encourage you to please do one or more of the eight Simple Acts, that can all be done at home, inspired by the theme ‘Imagine’. Simple Acts are everyday actions we can all do to stand with refugees and make new connections in our communities.