To mark Deaf Awareness Week (1-7 May 2023) we asked award-winning author and activist Dr Paddy Ladd to share an overview of Deaf Culture, history and sign language. In this blog he explains why it is still under threat.

For the first 120 years of Deaf education, sign languages were the medium of education all over the world. Deaf teachers were ubiquitous and in the USA they made up 40% of the total. They also founded many Deaf schools (24 in the USA alone) including sailing to other continents to do so. The first two Australian schools were founded by Britons. French Deaf teachers founded schools in Brazil, Mexico, the USA and so on.

From 1880 onwards, a movement termed Oralism gained control of Deaf education around the world. Those leading the movement were obsessed with removing anything ‘Deaf’ from Deaf education under the guise of promoting speech alone as the best method of education (Deaf schools in fact graduated many whose speech was good). Sign languages were banned, and Deaf teachers were fired. Deaf history, culture, arts and pedagogical wisdom were all removed from education systems all round the world, until their (limited) return during the Deaf resurgence of the late 1970s. By then, several generations of Deaf children had suffered serious illiteracy, with school leavers having an average reading age of 8½, seriously reducing the numbers of potential Deaf leaders and damaging the communities accordingly.

Even then the gains were only partial, because Oralists then seized on the new concept of ‘inclusion’ to close Deaf schools and place children in mainstream schools, often completely isolated from other Deaf children. At the present time around 90% are mainstreamed, and the educational and psychological damage has been profound. Deaf children suffer acquired mental ill-health at double the rate of the rest of the population.

We were influenced by the 1960s and the positive changes in the world and applied them to our situation. Our priority was Deaf education because the future health of any community depends on its children. Back then there were only a handful of Deaf professionals, and Deaf pride was almost totally absent. It was a huge task, but we and hearing allies made significant inroads. Our most successful campaign was achieving Deaf TV programming, which has changed the world in innumerable ways.

Deafhood is a concept that draws together all the positive achievements of Deaf people, and the positive qualities Deaf communities bring to the world. It also specifically analyses the modes of oppression affecting Deaf people and helps them realise how their identities have been damaged – encouraging them to enlarge and strengthen their Deaf identities. My book, Understanding Deaf Culture: In Search of Deafhood (2003), has had a major global impact and been translated into seven languages.

I devised the culture-linguistic model to highlight the weaknesses of the Social Model of Disability when applied to Deaf communities. The Social Model focuses on individual access to society. We share this with disabled people. But because we have our own languages and cultures, we also have collective group identities and rights that this model does not touch on. Deaf schools and Deaf clubs are central to this model because they are the places where the languages and cultures are learned, whereas the Social Model emphasises inclusion as the be all and end all of disability education. There is much more that can be said – this is just the tip of the iceberg.

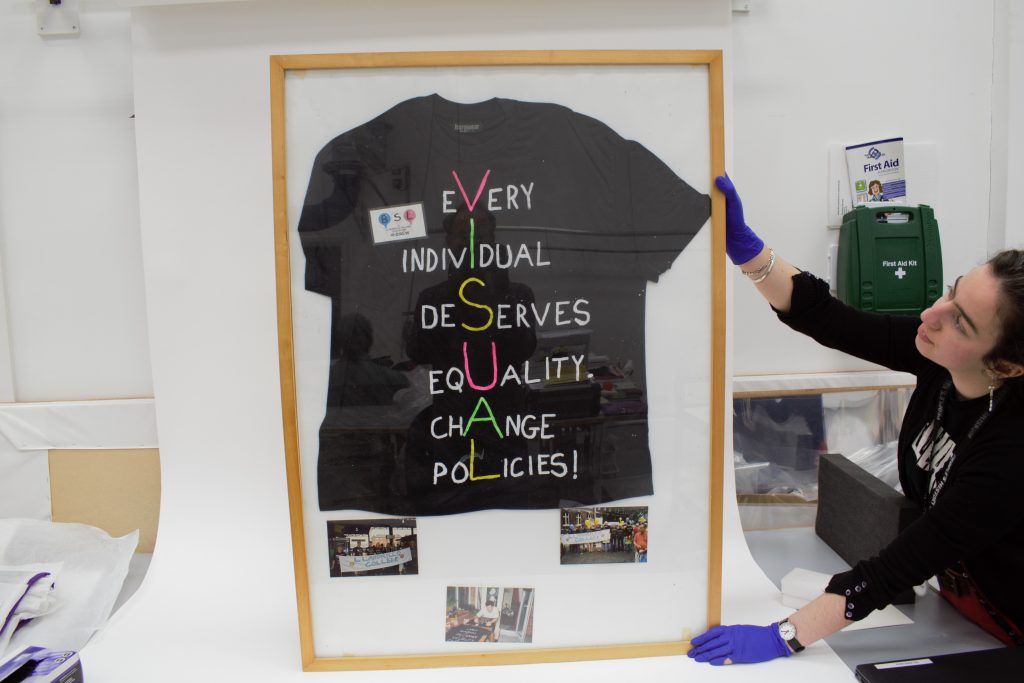

Over the decades we have tried many strategies to defeat Oralism, and we came to realise that the best way to do so was to campaign for the same rights as other ‘indigenous’ minorities and cultures – in the UK that would be Gaelic and Welsh. In 1998 we founded the FDP (Federation of Deaf People) and inaugurated the first Deaf marches, leading to a very token recognition in 2003.

However, the organisations holding power over Deaf people tried to divert this aim into a watered-down campaign for more interpreters and BSL teachers to teach hearing people BSL, under the guise of the outdated Social Model.

This situation still holds sway today, and the recent Bills in Scotland and the UK, although they are laudable steps forward, are still a thousand miles from what is needed. BSL is still under threat because of mainstreaming and the closure of Deaf schools and Deaf clubs. We are racing against time to try and find all these isolated Deaf children and give them belated access to our communities, cultures, arts, sports and so on.

Power is still in the hands of those who espouse the medical and social models. Deaf activists are getting older, and more tired and burnt out, and mainstreaming has reduced the numbers of young people to replace them. Proper official BSL recognition is vital for turning the tide. To do all this we need hearing allies – we need to break down the walls of silence that surround these generations of Deaf child abuse.

I am writing four books about the accomplishments of Deaf teachers and the need for the system to accept that they are the model for what needs to happen – total change of the education systems. These are the first ever books of this kind in the world, which illustrates the scale of oralist oppression.

I also believe that Deaf-written SignSong is a vital way of getting society’s attention and have published two books of these (one being a musical) as a stepping stone to obtain wider attention and artistic grants.

Dr Paddy Ladd is an author, activist, and researcher of Deaf Culture. He was lecturer and MSc co-ordinator at the Centre for Deaf Studies at the University of Bristol.

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM.