To mark ten years in People’s History Museum’s (PHM) current home, the museum team picked out ten pieces that we believed capture the ethos, spirit and importance of PHM’s collection. This month Collections Manager Sam Jenkins pieces to together clues from the past to reveal the story of one of PHM’s most treasured objects.

Objects from the working class are still very rare in museums, especially from key moments like the Peterloo Massacre. Despite the 60,000 person strong crowd, the vast majority of objects that help us to tell the story of the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester are either related to the yeomanry and magistrates, or are commemorative objects created after the event. In museums across England, there are very few objects that can help tell us about the protestors themselves.

This isn’t just because working class objects weren’t collected by museums at the time (though, of course, they weren’t) but also because of the harsh laws that were put into place after the massacre. Following the horrific day, laws were passed that restricted people’s rights to criticise the government, including restricting the right for groups to meet. To be found in possession of any object that aligned you to the radical cause was a very big risk, and not one that many people would have taken.

With these objects being so rare, it was almost unbelievable to be offered a Peterloo cane – something that had a high chance of being used by a member of the crowd that was assembled in Manchester on 16 August 1819.

The donor contacted the museum, as he had heard about our exhibition Disrupt? Peterloo and Protest (23 March 2019 – 23 February 2020) and wanted to offer us a family heirloom – a cane with a sentence about Peterloo scratched into it:

‘I was one of the dreadfull [sic] bludgeons seen on the fields of PETERLOO’

As soon as it was offered, we knew that we would have to see it to believe it – and to figure out what its story was. With this sentence scratched into it, there was a split chance between it being a souvenir, taken by one of the yeomanry or a Special Constable, or a memento kept by a member of the crowd, and we needed to figure out which. After a discussion with the museum’s Acquisitions Panel, we agreed that I would meet the donor and have a closer look at the cane, to be brought in to the museum for a full investigation.

As there is no possibility of a photograph or an eye witness to confirm if an object was really present at a major event such as Peterloo, we have to examine these objects carefully to pull out all the clues that we can.

When I met the donor, and saw the cane for the first time, it was clear that it was very special. The donor told me how it had been passed down through his family and had slowly lost the connection of what, exactly ‘Peterloo’ was; when he heard about the museum’s exhibition, Disrupt? Peterloo and Protest, he immediately thought about the cane sitting in his wardrobe and decided to offer it to us. He had also started to trace his family tree, managing to make it up to a Charles Worsley who was a joiner in the Manchester area around 1819. From that, we knew that the family were in the right place at the right time.

Looking at the cane that first time, it became evident that there was far more written on it than had first been noticed. Along with the clearest inscription ‘I was one of the dreadfull [sic] bludgeons seen on the fields of PETERLOO’ was another line of carvings that looked like names, starting with ‘HUNT’ and ending with ‘WORSLEY’. It was clear that we needed to look in closer detail, and for longer.

With the donor agreeing to deposit the cane for us to research before officially deciding on the acquisition, I was able to take longer and use different techniques to try and figure out as many of the inscriptions as possible. Using raking light and photo editing, I managed to decipher the list of names:

HUNT CARTWRIGHT COBBE WOOLER KNIGHT WORSLEY

It seemed very likely that Hunt referred to Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt, the key speaker at Peterloo, but what of the others? Cartwright could be Major Cartwright, a nationally respected reformer, and Wooler was a journalist who had been associated with the radical movement. John Knight was also on the speakers stand with Hunt, so only the name ‘Cobbe’ was unexplained (unless this is actually ‘Cobbett’, as in pamphleteer and journalist of the time, William Cobbett). Finally, came the surname of the owner, ‘Worsley’.

This really became clear when, with the aid of PHM’s Conservation Team, I was able to see the cane under UV light. While looking at the cane with our conservators, Jenny and Kloe, we noticed that there were inked drawings on and near the handle. After spending a few minutes wondering what the spade-like drawing was, it came to us – it was a cap of liberty! Looking closely revealed two caps of liberty and a flying flag drawn onto the cane. Under the UV light it was clear that these were underneath a layer of varnish, while the two carved inscriptions were made after the varnish had been put on.

We finally had enough evidence to piece together the story of the cane. The drawings of symbols of radicalism suggested that the cane had been carried by a member of the crowd. The inscription about Peterloo could have been the boast of a victor, but the inclusion of the surname of the owner alongside those of Hunt, Cartwright and Knight suggested instead that it was a satirical comment on the claims that the protestors had been armed. The family history tied the cane to the area around Manchester at the right time, and to a man who would have been respectable enough to carry a cane as part of his Sunday best, but still would not have held the right to vote.

But the story isn’t yet wholly complete, as there are more inscriptions that still need to be deciphered. Part of one of the inscriptions says ‘brought to justice’ but the rest of the sentence is too unclear to make out using the methods we have available. and the others are even harder to see, but my gut feeling is that one of them says ‘Liberty’.

This cane is a real connection to the men and women who met at St Peter’s Field in Manchester to call for reform, and were cut down for it. Such a tangible link to working class history is like gold dust, and it’s a real privilege to be able to share this story with future generations.

The Peterloo cane is on public display in Main Gallery One until January 2021, coinciding with the screening of a new BBC Four documentary with historian Lucy Worsley, some of which was filmed at the museum. In the programme, which will broadcast in the autumn, Lucy is introduced to the Peterloo cane.

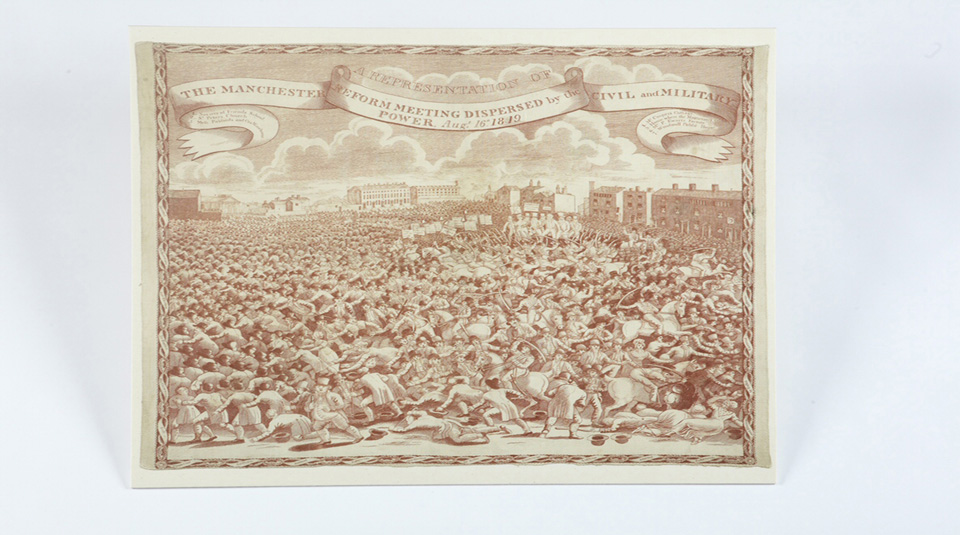

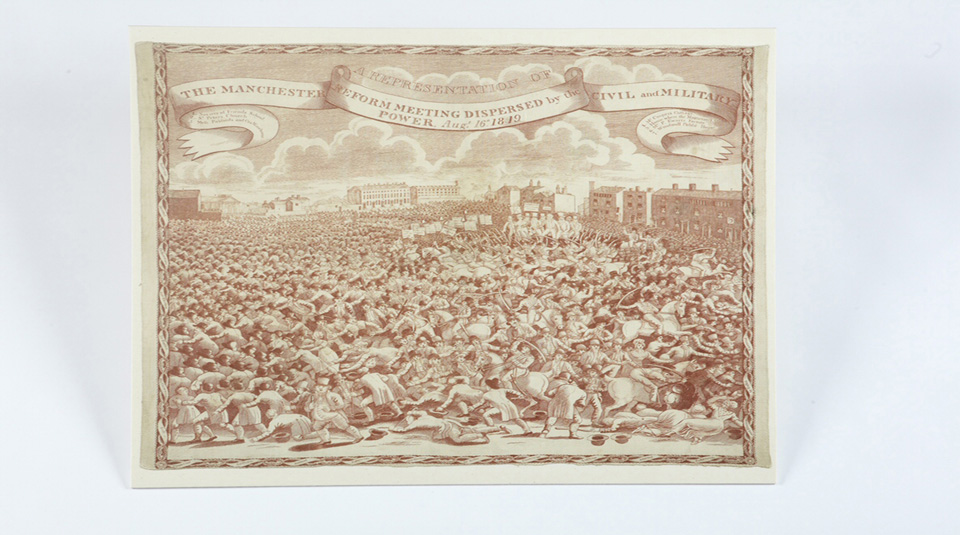

The meeting held on St Peter’s Field in Manchester on 16 August 1819 was a protest for rights and representation and is the point at which the story of revolution begins in the main galleries of People’s History Museum. The peaceful protest was broken up by the authorities leading to the death of 18 people and the injury of over 700. Find out more about what happened at the Peterloo Massacre from PHM Researcher Dr Shirin Hirsch.

2020 marks the tenth anniversary of the museum being in its current home, which prompted us to pick out ten of our favourite items; these also include the 1908 Manchester suffragette banner, a commemorative plate to the Equal Pay Act of 1970, and a placard from the 2019 Youth Climate Strike in Manchester. Explore the stories behind all these fascinating objects.