In this guest blog Viv Anderson MBE talks to PHM about his life growing up in Nottingham from Jamaican descent, his life in the game and call for affirmative action.

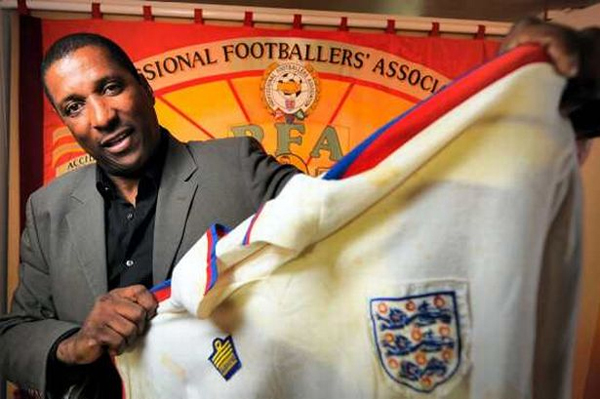

Viv Anderson MBE was the first black England international football player, when he made his debut against Czechoslovakia in 1978. He went on to win 30 caps for the Three Lions in a decorated career that saw him represent Nottingham Forest, Arsenal, Manchester United and Sheffield Wednesday and win two league titles, two league cups and two European Cups along the way. The Football Association (The FA) is the Radical Sponsor of Viv Anderson MBE at PHM, part of the museum’s Join the Radicals fundraising scheme.

‘I still remember when I first met up with the England squad and I saw the likes of Kevin Keegan, Trevor Brooking, Bob Latchford and Tony Currie.

They were the people that I grew up watching on television, so I was in awe of them anyway and now I was on the same pitch as them. But I remember Kevin Keegan said to me: ‘You wouldn’t be here if they didn’t think you were good enough.’

So clearly, they thought I was good enough, but you just have to portray that on the football field and that’s what I tried to do. I just wanted to make sure I was back in the next squad and the one after that.

At the time, I wasn’t aware of the significance of being the first black England international. We were all young footballers trying to get on and make a living. What I would like to say though is that the likes of Cyrille Regis and Laurie Cunningham, who are sadly no longer with us, should really be mentioned at this stage.

I saw Cyrille a couple of months before he died earlier this year and he looked so fit and healthy. The last thing you would’ve thought is that he would die a few weeks later, so you’ve got to seize every moment and opportunity to the full because you never know what’s around the corner and Cyrille was a great example of that.

Although we didn’t grow up together we were of similar ages and we came through at a similar sort of time with our clubs.

For me and Laurie, it was a question of who would be the first black player to play for England. Laurie ended up being the first when he played for the under 21s and I was then lucky enough to become the first senior international and it’s something I’m obviously still very proud of. To be the first at anything, you’ve got to be proud.

I remember my former Manchester United team mate Norman Whiteside, who is still the youngest player to have played in a World Cup Final, telling me that one day his record will be beaten but mine will never be beaten. It’s an analogy I still tell people today, so I’m proud and privileged to have been the first black England international.

My parents came to England from Jamaica and I was born in and raised in Nottingham.

Growing up, I remember it was always sportspeople who I looked up to. I remember Clyde Best, seeing him on the television and he was the first black person I ever saw on TV, so I just thought at the time that he must be a good player.

I then went to Manchester United at an early age and from 15 or 16, every school holiday I went up there as a school boy and I saw George Best, Denis Law and Bobby Charlton training and they were also great inspirations to me.

I could say it was Nelson Mandela, but really, it was always people in sport that I recognised. Nelson Mandela was a politician and an activist, so I wasn’t really into that mind set growing up. It was people in my sport who stood out to me, like Clyde Best and Best, Law and Charlton.

A lot has been said over the years about the climate in football for black players at that time, when me, Cyrille, Laurie and Brendan Batson were coming through and it was very tough.

But we were fortunate in a way because we had strong managers. I had Brian Clough at Forest and they had Ron Atkinson at West Brom and I think they helped and guided us through the murky waters.

I recall Cloughie saying to me early on: ‘If you’re going to let people like that dictate to you, you’re no good to me and you’re no good to yourself.’

And I desperately wanted to be a footballer, so I just dismissed anything that was thrown at me, literally, and tried to get on with playing football, which I loved.

It was as simple as that and I think you had to be as single-minded as that because if you let the periphery stuff affect you, you wouldn’t have a career and I was very focused on being a footballer and I enjoyed a great career.

For me, it felt like a natural progression to become a coach when my playing days were coming to an end at Sheffield Wednesday.

I was persuaded to go and be the player manager at Barnsley by the chairman, who was John Dennis at the time. That was over 20 odd years ago now. I took Danny Wilson with me as assistant because I knew how tough being a player manager would be.

At the time there was Keith Alexander, who was also born and bred in Nottingham, who got the job at Lincoln City just before I went to Barnsley to become one of the first black managers.

The talk back then, when Keith got his job and I got the job at Barnsley, was that there was going to be a new revolution with more black managers, more Asian managers and everything else that goes with it.

But that never materialised, so clearly, we’ve got a problem in our society where people think that black players are good footballers but they don’t make good managers.

So I think something has to give. There’s the Rooney Rule which has been talked about, and since it’s over 20 years since I was a manager and nothing has really changed, let’s try it.

We should try anything to help bridge that gap, because in my view there’s too many great footballers who have been wasted because they’re not involved in football. People like Paul Ince, Sol Campbell, Andy Cole, Rio Ferdinand and the list goes on and on. Surely, with the level they have played at, they can give something back to the next generation of footballers.’

Viv Anderson MBE.

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM. Photographs supplied by contributor.

People’s History Museum (PHM) is proud to honour the Radicals who believe in ideas worth fighting for. Like Viv Anderson MBE, there are many stories of Radical thinkers told throughout the museum and still lots more to be explored.

Find out how you can support PHM. From just £30 per year, you can Join the Radicals or like The FA, become a Radical Sponsor and help the museum continue to celebrate and commemorate those people who campaign for ideas worth fighting for. Your support can help us engage more people in democracy, exploring its development in the past, present and future of Britain.

Our friends at The FA have published a great piece for Black History Month looking at ten of English football’s black pioneers, read it here.