As 2020 draws to a close and with Britain’s only national museum of democracy under threat, we’ve got an inspirational seven minute read for you from Co-Chair and Trustee at People’s History Museum (PHM), Martin Carr.

It was Winston Churchill who quipped that ‘Democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others’. Whilst history has proved that to be undoubtedly true, mature democracies like ours can feel like they are in pretty poor shape and increasingly failing the people.

Question is, what can we the people do about it? Well, the most precious facet of a functioning democracy is that we are free to protest, to raise our voices, and to demand change.

According to The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index, which provides a snapshot of the state of democracy worldwide, the latest global score for democracy fell to its lowest since the Index was first produced in 2006.

It claims that we are suffering a ‘global democratic regression’ and cites recent surveys into attitudes towards democracy that reveal what it calls a ‘disjuncture between still-high levels of public support for democracy across the globe and deep popular disappointment with the functioning of democracy and systems of political representation’.

So, we like the idea of democracy (perhaps acknowledging that it beats any alternative), but in practice the way it plays out is just not performing for us.

But why not, here in the UK, in particular?

There are myriad opinions as to what isn’t working, and a Kings College London paper of July 2020 even went so far as to ask the question, ‘Is the Government actively undermining British democracy?’ – pointing out that, since Prime Minister Boris Johnson was voted into power, his government has threatened parliamentary sovereignty, the independence of the judiciary, the independence of the BBC, the individual right to trial by jury and has undermined public confidence in all institutions of governance to an extent never seen before.

Regardless of the motivation on the part of the current UK government, as citizens we both see and feel the effects of an under performing democracy, and we all witness, even if not everyone actively shares, the rise in dissatisfaction with our politics, our politicians and the way in which we are represented and governed.

And this clearly isn’t just a concern for Britain.

The ‘failure’ of democracy to represent the interests of people in the US was reinforced in a Princeton University study, back in 2014, which concluded that ‘even when fairly large majorities of Americans favour policy change, they generally do not get it. The preferences of the average American appear to have only a minuscule, near-zero impact upon public policy.’

And, even before this research, Nobel Prize winner for Economics Paul Krugman had already called the US ‘a democracy in name only’.

How do the failings in mature democracies such as the UK’s and in the US manifest themselves? The Economist Intelligence Unit report summarises the main outcomes of the ‘democracy recession’ as:

Its conclusion, given these increasing failings, is that we have witnessed the retreat of political elites and parties from engagement with their electorates; resulting in falling levels of popular trust in political institutions and parties, declining political engagement, and a growing resentment among electorates at the lack of political representation.

So, if we were to choose to, it would perhaps be easy to become depressed at both a system of democracy – first past the post – that encourages polarisation and also by an ever increasing belief that decision making lies ever further away from we, the people, and that our voice and our interests count for very little.

But, against such a prevailingly gloomy picture, where the state of democracy in the UK and elsewhere is increasingly worrying, what can we do about it, and who is doing it?

If history teaches us anything, it is that we the people simply refuse to accept what patently doesn’t work for us. And that opposition to the absence – or diminution – of our rights and of equality and representation, that have been so hard won, finds a way to be heard, to be taken notice of, and to help manifest positive change.

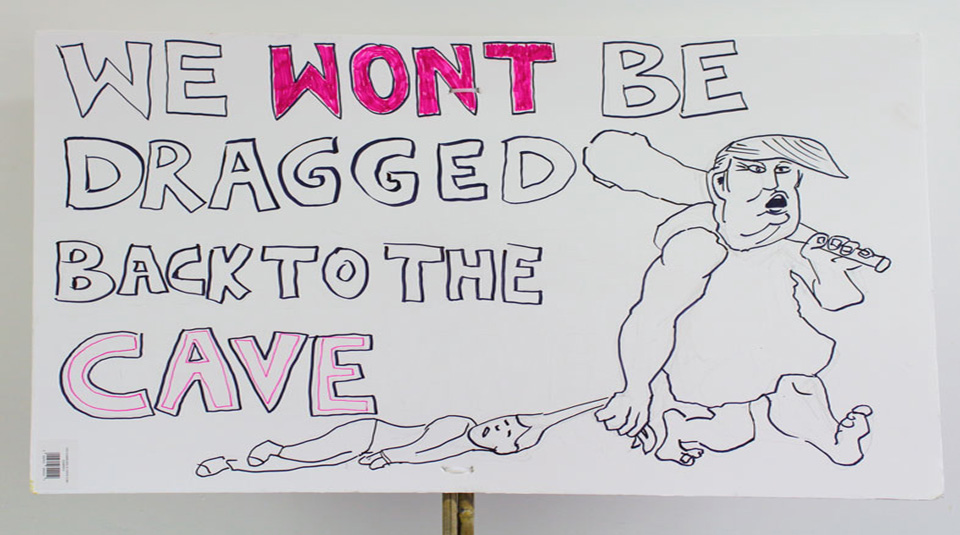

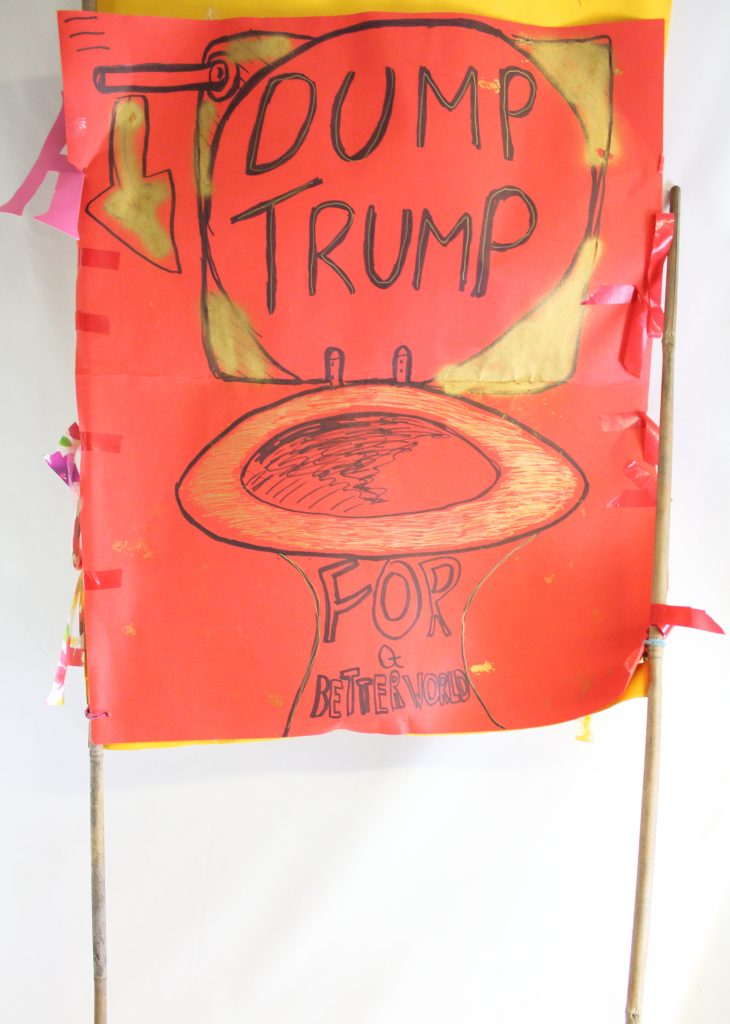

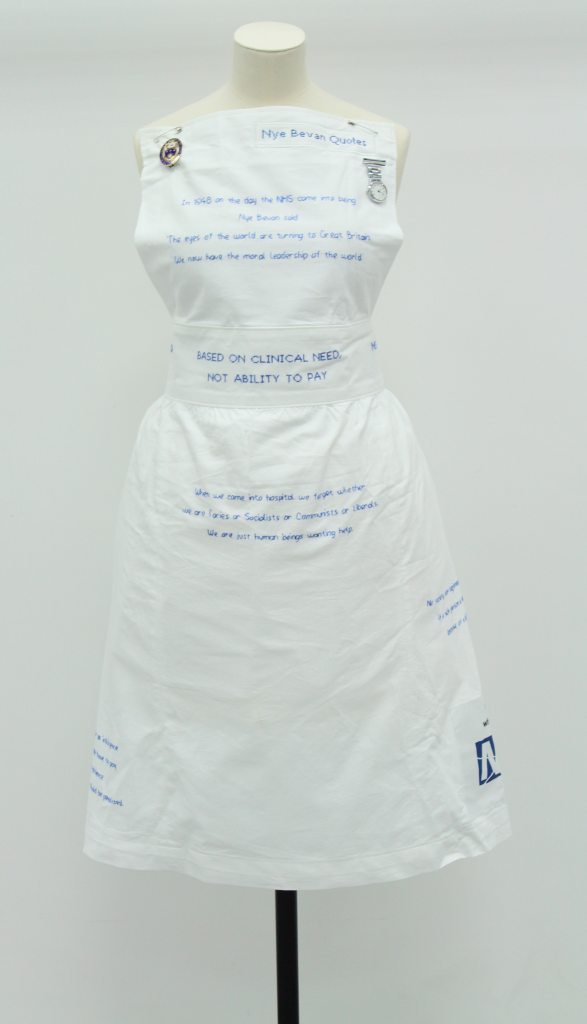

If there is one theme to be heard again and again at People’s History Museum, it is that protest and activism have become ingrained in our culture. It is one of the cornerstones and strengths of our, albeit dysfunctional, democracy. And the evidence of its effectiveness is everywhere in the museum; demonstrating how the disaffected have found their voice, articulating demands that have influenced tangible change. And at a time when people may increasingly feel ignored or disaffected, and it may be difficult to see and hear evidence of this activism, it is undoubtedly present.

In fact, an increasing number of us are taking action, often in new ways.

For example, between January and June 2020 and the corresponding period in 2019, change.org experienced a 119% increase in the number of people starting petitions in the UK – and a 116% increase in those signing them. So, while trust and transparency appear to be low and falling, it is a fact that grassroots protest – of registering disapproval, of demanding positive change, of speaking your mind – is alive and well.

Away from the grassroots, and contributing to the context and backdrop in front of which local activism plays out, large scale protests garner significant media coverage and can dominate the news agenda – helping issues to both become and remain high profile. Black Lives Matter (BLM), born of outrage and anger, amplified by media and online, and fuelled by an unshakeable refusal to allow the status quo to remain, has become a significant global movement with an ongoing record of catalysing significant change in political and civic life.

Global protest movements such as BLM or Greta Thunberg’s school strike for climate will ensure that a generation finds and maintains its voice over a lifetime, catalysing change. In addition, there are examples of individuals who have successfully used their profile and reputation to register protest, gaining wide support and building pressure that has helped bring about positive change. Here in Greater Manchester, Manchester United footballer Marcus Rashford’s ‘victory’ in achieving an extension of free school meals during the Covid-19 pandemic is the most current and best known example.

But – and extremely importantly – effective activism isn’t just the domain of the famous and well known – people or movements. Early in the Covid-19 pandemic, junior doctor Rebecca McCauley started a change.org petition expressing frustration at the lack of testing for NHS workers, calling for them to be prioritised. The petition quickly gathered more than 1.5 million signatures, was picked up by national media and within days the government promised to make NHS staff a priority for tests.

Commenting on the rise in activism experienced through channels such as change.org, Sophie Walker, author of Five Rules for Rebellion; Let’s Change the World Ourselves says ‘there is a lot that is depressing about the state of the world. But the responding rise in activism is a cheering counter-energy’.

So, let’s celebrate this counter-energy. As an increasing number of us find new ways to register our disapproval, to stand up for what we believe in, and to demand positive change, at People’s History Museum we recognise the unique obligation and opportunity we have to help provide a focal point, as well as a repository for stories, and a space where all of this positive activism can be documented, celebrated and encouraged. Whether by sharing and exploring the impact on us all of momentous global change born of activism and protest, or by inspiring and motivating local and grassroots activism – online and in our communities – the national museum of democracy has an important and active role to play.

And we intend to play our part to the fullest; demonstrating what we can all learn from centuries of protest and activism, capturing and interpreting the national or global zeitgeist, and also by putting ourselves at the service of today’s and tomorrow’s activists and change makers.

No matter how poorly we may feel we are governed, long live activism; it’s never felt more vital.

PHM has recently launched a crowdfunder aimed at raising £25,000 to help secure the future and ensure the survival of the national museum of democracy following the pressures that it has faced as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic.

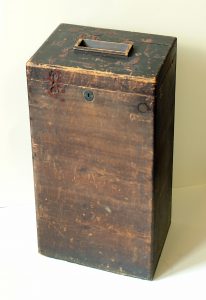

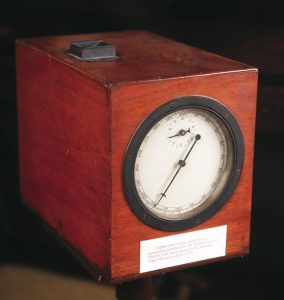

Watch this short video from Cyfarthfa Castle Museum & Art Gallery featuring three ballot boxes made by William Gould, the creator of the Merthyr ballot box on display in Main Gallery One at People’s History Museum.

Find out about the Pontefract secret ballot box – used in the first election held after the passing of the 1872 Ballot Act, and featured in PHM’s Disrupt? Peterloo and Protest exhibition (23 March 2019 – 23 February 2020) – in this previous blog from our friends at Wakefield Council – Wakefield Museums.