2024 marks two significant anniversaries of miners’ strikes in Britain. The 1974 Miners’ Strike and the strike of 1984 to 1985, that is etched in the memories of many.

In this second of a series of three blogs exploring these miners’ strikes, Amy Todd, a PhD student working for People’s History Museum (PHM), explores the women’s movement against pit closures during the 1984 to 1985 Miners’ Strike.

As part of this series you can also read a blog from PHM Researcher Dr Shirin Hirsch, taking us back to the earlier and lesser known strikes including what took place during the 1974 Miners’ Strike and the legacy this created for the years that followed. We’ll also hear from Dr Bob Dinn, Visitor Experience Supervisor at PHM, who has written about the events of the 1984 to 1985 Miners’ Strike.

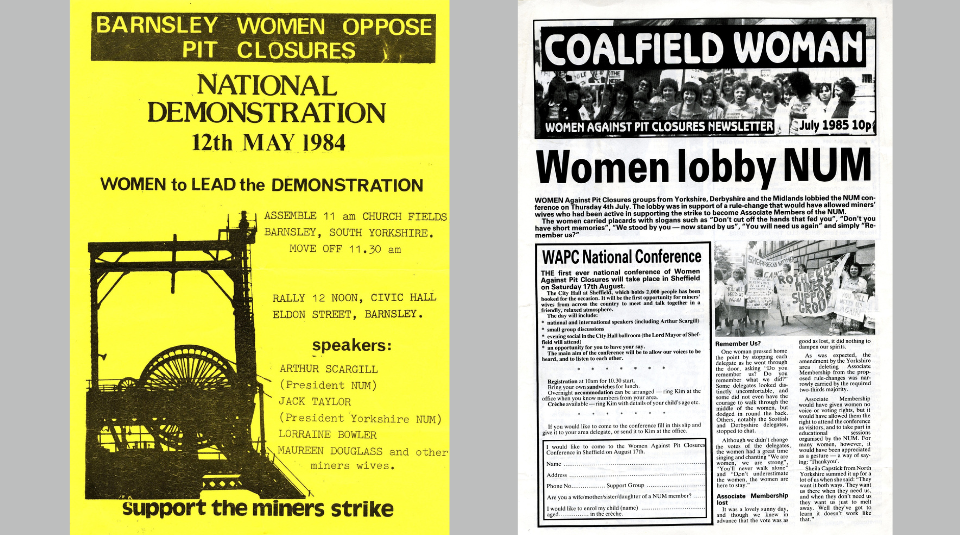

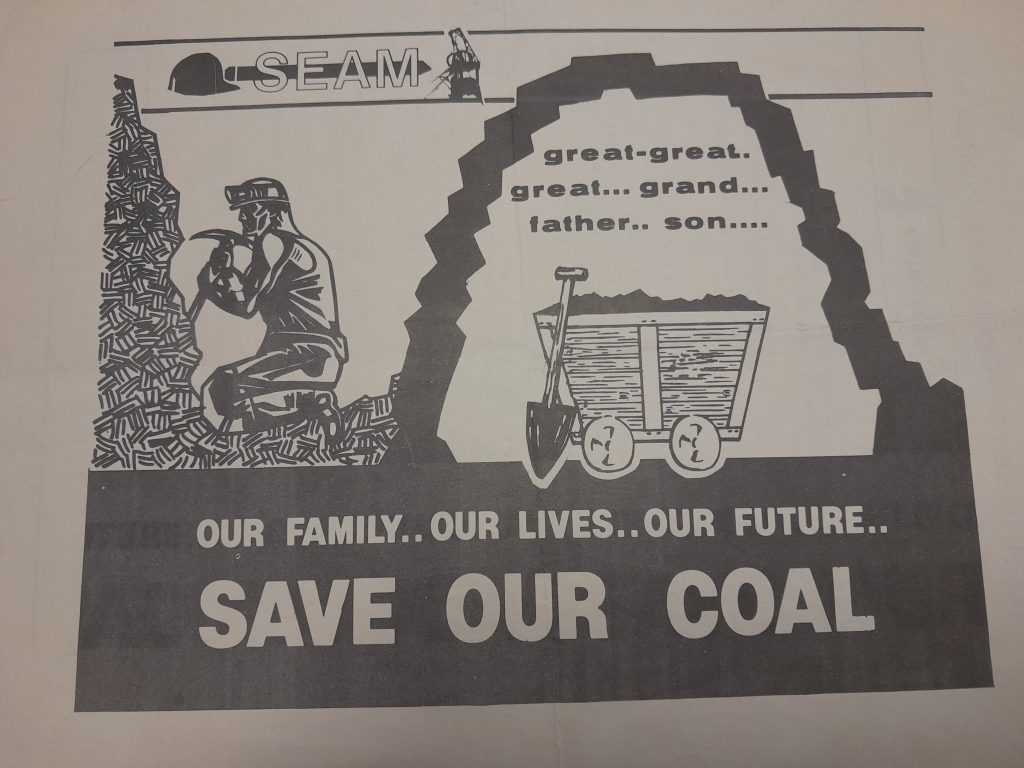

Many women and miners’ wives, up and down the country, began organising support of the strike at the onset of the Miners’ Strike (1984-1985). Starting as autonomous regional groups, these soon developed into a national infrastructure that many (but not all) of the groups joined. This became the National Women Against Pit Closures (NWAPC).

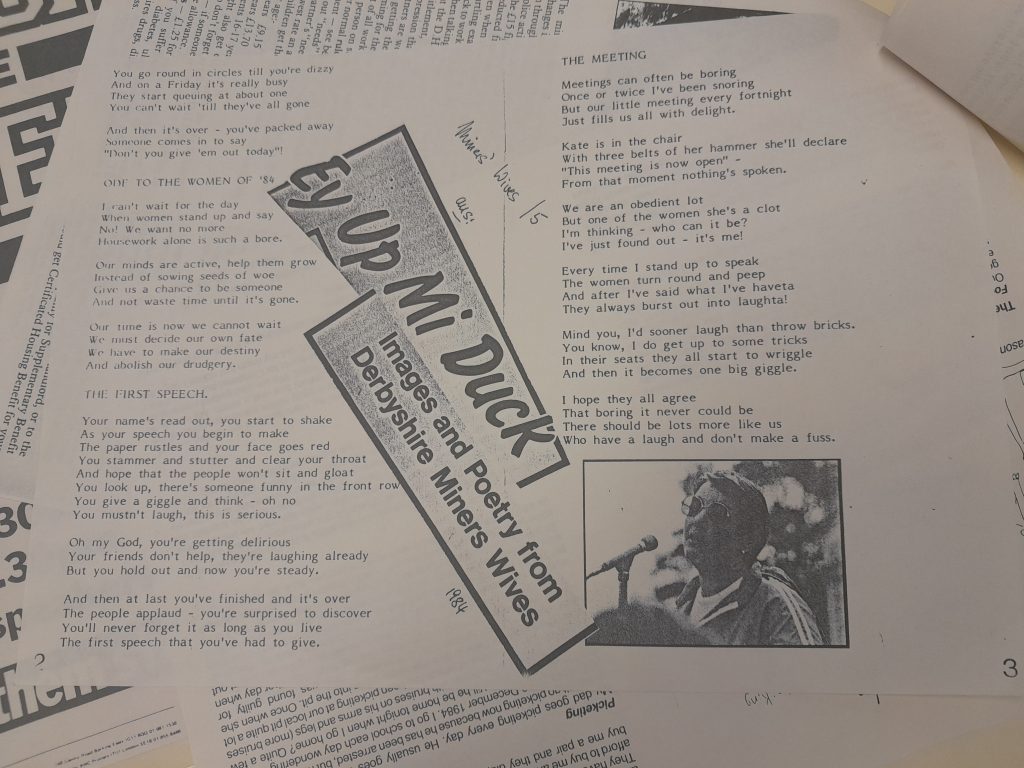

Women of the Women Against Pit Closures (WAPC) group took it upon themselves to be responsible for fundraising, picketing, secondary striking, organising rallying events, public speaking, hosting meetings, and providing essential food and sanitary items for families across the country. The women wrote political material such as pamphlets and articles, promoted the cause through the press, and travelled across the country networking with other activist groups.

The women’s unpaid labour and essential support contributed to both the strength and the length of the Miners’ Strike, and led to a more positive representation of the strike in the press.

Whilst many of these women were new to activism and chose to self-style themselves as ‘just miners’ wives’, many women of the WAPC brought with them techniques, experience, and skills from the left and labour movements. These movements included the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), women’s liberation, Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), Trotskyist groups like International Socialist, trade union activism and/or support, and from growing up in politically active families and communities. The post war period had a progressive, affluent, and modernising impact on work, education, women’s roles, family roles and structures, and social mobility, as did the women’s liberation movement of the 1960s onwards. The 1970s and 1980s were also an era which saw many developments within socialist circles in the UK (notably Eurocommunist theory). All these aspects shaped the discussions, actions, activism, and tensions which took place within WAPC circles, and their communications with the press, the public, the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), and non-affiliated women’s groups – such as the Barnsley Miners Wives Action Group, who did not join the national WAPC framework.

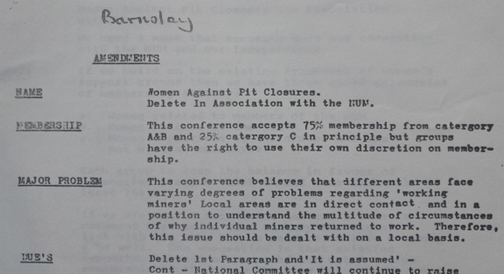

Once the groups had formed and the successes of their activities such as soup kitchens and fundraising were celebrated (despite very little financial support from the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) itself), tensions within the groups appeared. Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite and Natalie Thomlinson in Women and the Miners’ Strike, 1984-1985 (2023) state that the groups were ‘divided over whether the movement should aim solely to support the strike, or whether it should have broader aims relating to women’s lives, gender, and feminism’.

This tension arose when women who had joined Women Against Pit Closures (WAPC) groups to support the strikes and the mining families, made connections between the attitudes of the miners, the NUM, and the press, and their experience of frustration and sexism throughout the women’s liberation movement a decade earlier. These frustrations, which were central to socialist feminist consciousness raising and theoretical debates, were depicted in publications such as the British feminist-socialist periodical Red Rag: a Magazine of Liberation (1972-1980). The magazine dissented against feminist and socialist conceptions of the time and developed new debates and conceptions of family, the state, gender, and sexuality, and whole new fields of inquiry including documenting and researching women’s history. The editors also questioned existing structures of power and organising, and drew from the New Left, New Social Movement Theory, and feminism to advocate for redistributive and pre-figurative grassroot approaches. This was emblematic of the different visions of socialism that the old and new left were competing over in the 1980s.

Barnsley activist Lorraine Bowler explained, ‘We as women have not often been encouraged to be actively involved in trade unions and organisation. It’s always been an area that’s seemed to belong to men. We’re seen to be the domesticated element to the family … I have seen change coming for years and the last weeks has seen it at its best. If this government thinks its fight is only with the miners, they are sadly mistaken. They are now fighting men, women, and families.’ 1.

An outcome of this tension led to the proposed ‘75% rule’ as evidenced in the archive document shown above. The rule of 75% representation of ‘A&B category’ membership was proposed and supported by women of WAPC who wanted to ensure miners’ wives with direct experience of the strike were in charge. The Barnsley women’s group was to be impacted the most by these tensions and decided in the end to split into two groups; the Barnsley Miners Action Group (later re-branded as the Barnsley Miners Wives Action Group), who worked closely with NUM President Arthur Scargill who took on the 75% rule, and the Barnsley WAPC who did not take on the 75% rule and carried out work autonomously.

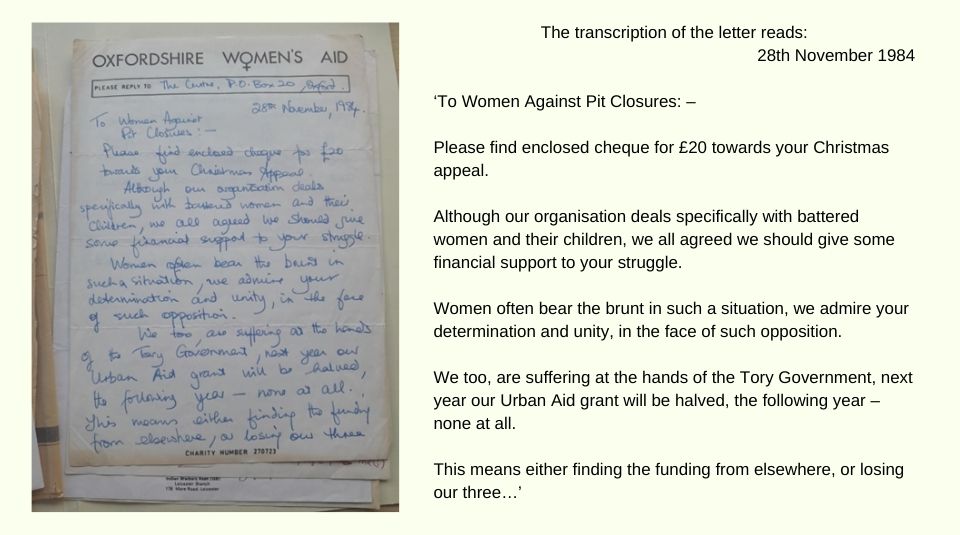

Despite these tensions, solidarity and learning did develop. As Nottingham activist and Miners’ Strike supporter Joan Witham describes, ‘Our world got bigger – professionals, feminists, punks, lesbians and gays, black people and Asians, we met them all and we stopped judging people by how they looked or how they spoke, we’re all people.’

Solidarity could also be found between groups and communities suffering under the Conservative government’s policies and cuts. A letter from Oxfordshire Women’s Aid in the museum’s collection shows the intersectionality of feminists of the time who, even though they were having to compete for resources, still reached out in understanding of their common struggle.

Leading socialist feminist figures such as Beatrix Campbell have reflected on the women’s roles and activism and suggested the work was less radical than we have been led to believe. She explains that the work of WAPC is an extension of the unpaid labour and caring that patriarchy expects of women, including activites such as running soup kitchens and fundraisers. She states that WAPC action did not challenge gender norms in a way that led to significant change within working class communities, or through representation in the media, which meant that women were still not seen as equal and competent political activists.

Nell Myers, who ran the NUM’s newspaper The Miner and was Arthur Scargill’s personal assistant, wrote and published a memo in August 1983 on Family and Community Involvement in the fight to save and expand the coal industry. She evidently saw the importance and political potential of the involvement of, and impact on the family that WAPC could influence.

The Labour History Archive & Study Centre at People’s History Museum is home to letters, campaigns, poetry, minutes, photographs, newspapers, and magazines; all detailing the activities of WAPC and the thoughts and feelings of those involved. The personal papers of the political activist and socialist feminist Hilary Wainwright are archived at the museum. Wainwright led the 1984 Miners’ Christmas Appeal and her files contain hundreds of handwritten heart-warming letters from across the world offering money to the appeal, with annotations such as ‘£5 – 50% of Christmas bonus’.

Authors Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite and Natalie Thomlinson are clear about the unique experience gained from researching and accessing original WAPC material, ‘There was a huge effort to document their activities by those involved, both at the time and shortly after the strike: this was one of the striking things about the movement. Poetry, writing, oral accounts and images went into books and pamphlets recording the women’s activism’.

Amy Todd is a PhD student at PHM and the University of Manchester. She is researching and writing the PhD thesis Total Liberation: Feminism, Socialism and Red Rag (1972-1980) and promoting PHM’s holdings in feminist history.

Read the first of three strike blogs for 2024 from Dr Shirin Hirsch, PHM Researcher and Lecturer in History at Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU), which takes us back to the earlier and lesser known strikes including what took place during the 1974 Miners’ Strike and the legacy this created for the years that followed.

View the Miners’ Strike 1984 to 1985 archive guide and discover material about the strike in the museum’s archive.

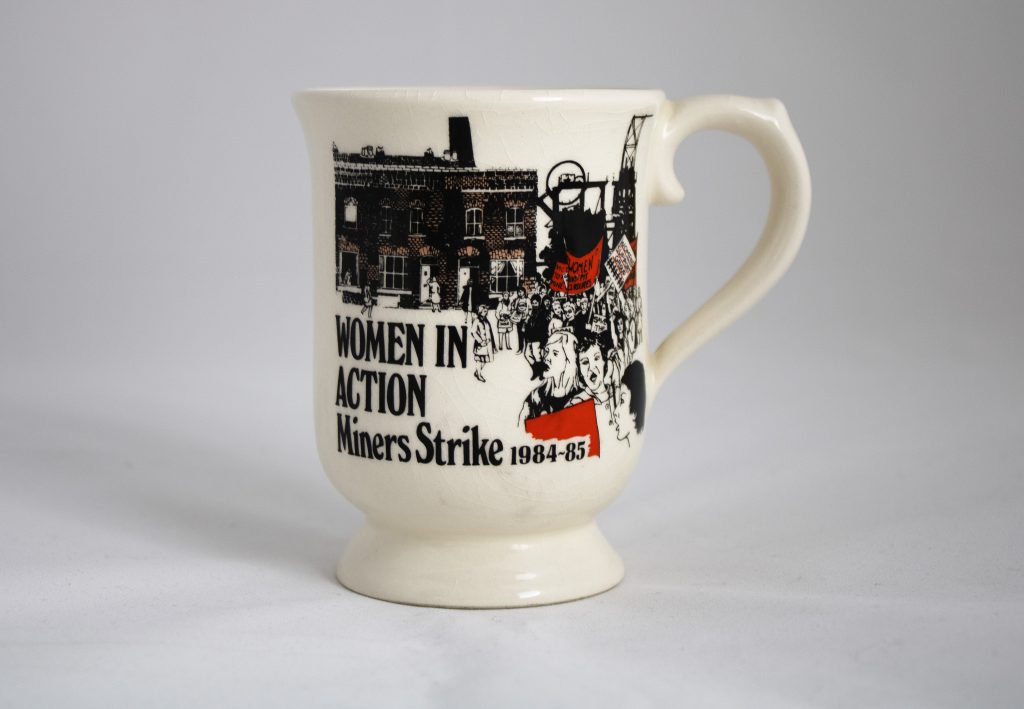

Visit the main galleries at People’s History Museum, where you can view objects, photographs, and participants’ testimonies from the 1984 to 1985 Miners’ Strike.

Don’t miss the Collection Spotlight in Gallery One, display of objects highlighting the role of women in the 1984 to 1985 Miners’ Strike.

Join The Fabric of Protest creative workshop for some stitching, chatting, and sharing; exploring Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners, and Women Against Pit Closures.

Explore PHM’s Miners’ Strike collections on an archive exploration and guided gallery tour.