Shirin Hirsch, Researcher at People’s History Museum, discusses Mike Leigh’s Peterloo film and introduces how you can discover the legacy of the Peterloo Massacre at PHM.

“Peterloo, lad! I know. I were theer as a young mon. We were howdin’ a meetin’ i’ Manchester – on Peter’s Field, – a meetin’ for eawr reets – for reets o’ mon, for liberty to vote, an’ speak, an’ write, an’ be eawrselves – honest, hard-workin’ folk. We wanted to live eawr own lives, an’ th’ upper classes wouldn’t let us…. Burns says as ‘Liberty’s a glorious feast.’ But th’ upper classes wouldn’t let us poor folk get a tast on it. When we cried… freedom o’ action they gav’ us t’ point of a sword. Never forget, lad! Let it sink i’ thi blood. Ston up an’ feight for t’ reets o’ mon – t’ reets o’ poor folk!”

So explained Joss Wrigley when asked what Peterloo was all about. Wrigley was only 19 years of age when he escaped the Manchester massacre of 1819, but the memory of Peterloo would never leave him. Wrigley remained throughout his life a poor handloom weaver. As an old man Wrigley was the leader of a ‘poverty stricken group’ of weavers who worked together in a cellar, and when the looms were quiet they talked by candlelight discussing politics and sharing working class history. We know all this because James Haslam, the son of one of these weavers, would sit and listen. What rang in the ears of this young boy, as he listened to the collective murmurings of the weavers, was Peterloo. He noted how, for Joss Wrigley, a survivor of the massacre, Peterloo had got into his blood “and he could not live it out.” Continuous years of poverty, together with years of political injustice and vagaries “had helped to nurse his hatred, which he resolutely passed on to others”. On the centenary of the Peterloo Massacre, the boy who had sat and listened to these conversations wrote down his memories of this group and they were published in The Manchester Guardian. Haslam asked: “And who can say how much the working classes owe to men like Joss Wrigley – a poor handloom weaver who from his obscurity passed on their spirit and opinions to coming generations?”

Mike Leigh’s film Peterloo continues to pass on this spirit. The film is a powerful cinematic intervention in bringing to life the mass organising, protest and repression of working class people in 1819. The scene of the Peterloo Massacre feels only too real as we watch the yeomanry (government forces) cut down protestors in St Peter’s Field. This is a history from below that Leigh’s film now brings vividly to our screens. In the questions and answers following the premier of the film, Mike Leigh and Maxine Peake both noted that the history of the massacre was rarely taught in schools and, even for people growing up in Manchester and Salford, the memory of Peterloo was far from widespread.

The film is immersed in historical sources and literature, including research undertaken here at People’s History Museum. We hope that this film will initiate a wider discussion and interest in the history of democracy and struggle – a springboard to PHM’s 2019 programme of exhibitions, events and learning sessions, marking the bicentenary of Peterloo, exploring the past present and future of protest.

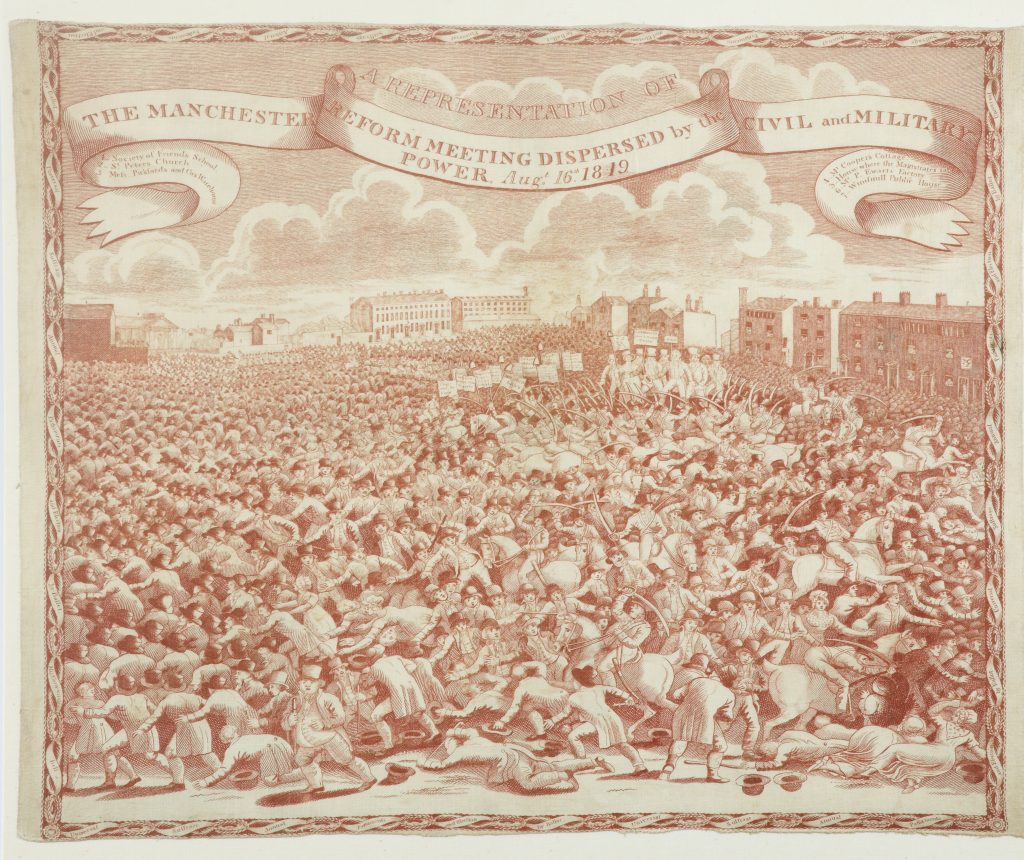

PHM’s collections tell the story of the Peterloo Massacre through visual materials and objects. On the handkerchief above, on display in Main Gallery One, you can see a snapshot of the Peterloo Massacre. The top of the handkerchief reads: ‘The Manchester Reform Meeting Dispersed by the Civil and Military Power’ and bordering the handkerchief are three demands ‘Universal Suffrage’, ‘Annual Parliament’ and ’Election by Ballot’. In the background you can see many of the buildings that surrounded St Peter’s Field, including a large cotton mill, a monument to the economic power of the rapidly growing industrial town of Manchester. Yet there was no Member of Parliament for the whole of Manchester at the turn of the 19th century.

There are estimates of 60,000 people congregating in St Peter’s Field at the moment the yeomanry attack on horseback. You can see on the handkerchief many different banners held, often with the cap of liberty on the top of the stick, a symbol of the French revolution. ‘Unite and be Free’ and ‘Taxation without representation is unjust and tyrannical’ are just some of the slogans shown. The ‘hustings’, where the speakers stood on a platform are also depicted, with Henry Hunt as the main orator, alongside speakers including Mary Fildes, the President of the Manchester Female Reform Society. On the handkerchief you can see one of the banners is inscribed with the words ‘Royton Female Union Society’, showing the large and organised section of women protestors emerging within the reform movement.

Despite the chaos shown in the picture, this was not an accidental massacre. In the film we watch the discussions as the local magistrates give the order to disperse the crowds, and in the build up to the protest the yeomanry are seen sharpening their sabres (swords with a curved blade). Two of these sabres are on display in Main Gallery One, passed down through generations and kept under a bed in Droylsden before being donated to the museum.

There are wide ranging estimates of how many were killed at Peterloo. It is hard to be exact with these statistics as there are huge debates as to who should be counted. Do we only count people who died on the day? Or people who died days, months or even years after, from lasting injuries? It is also highly likely that some of those killed are not on the surviving casualty lists, which were compiled not long after the massacre. Historian Michael Bush has carried out analysis of the casualty lists and estimates that 18 were killed at Peterloo, and other historians estimate around 700 were injured.

The handkerchief we have on display was just one way of keeping alive the memory of Peterloo. The British government was keen to cover up the massacre, imprisoning the reform leaders and clamping down on those who spoke out against the government. Many of the commemorative Peterloo objects on display in Main Gallery One were created to break through this repression as material ways of refusing to forget. To mark the bicentenary of Peterloo, PHM will continue this memory, not simply as a history lesson, but reflecting on protest and dissent from 1819 until the present day, and looking to protest of the future. Why not visit People’s History Museum and our Archive & Study Centre to continue the debate on the Peterloo Massacre and its impact today.

In our archive we hold newspapers from across the world reporting on the Peterloo Massacre.

In the museum shop we have a wide range of books on the Peterloo Massacre including:

Mark Krantz, Rise Like Lions: The History of the Peterloo Massacre, £3

This pamphlet has recently been republished by Bookmarks publishers – an accessible and exciting way into this history.

Joyce Marlow, The Peterloo Massacre, £9.99

A real classic on the massacre, recently republished by Ebury Press.

Graham Phythian, Peterloo: Voices, Sabres and Silence, £16.99

A new book based almost entirely on eyewitness reports and contemporary documents.

Jacqueline Riding, The Story of the Manchester Massacre: Peterloo, £25

Riding was the historical advisor for the Peterloo film and this is a new book analysing the massacre.

Shirin Hirsch is a historian based jointly at People’s History Museum and Manchester Metropolitan University.