To complement the public display of a suffragette tea set designed by Sylvia Pankhurst we asked Dr Alexandra Hughes-Johnson, suffrage historian and Women in the Humanities Research Co-ordinator at the University of Oxford, for the story of its former owner, suffragette Rose Lamartine Yates (1875-1954).

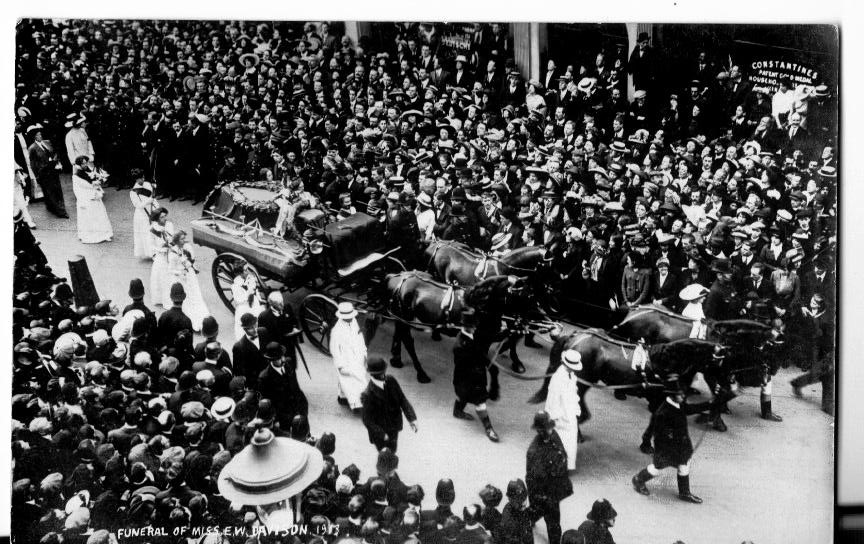

Until recently Rose Lamartine Yates has remained a relatively unknown figure in the history of the women’s suffrage movement and despite attempts by historians Elizabeth Crawford, Gillian Hawtin and Gail Cameron to shed light onto Rose’s suffrage career, she is often still remembered for her friendship with the Emily Wilding Davison and her role as the first guard of honour to her coffin at Emily’s funeral on the 14 June 1913.

Throughout the suffrage centenary, however, interest in Rose’s life and legacy has extended far beyond her friendship with Emily. Not only has Rose’s role as the Organising Secretary of the Wimbledon Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) been showcased in both the academic and heritage spheres, her contribution to the wartime suffrage campaign and her position as a London County Councillor and founding member of the Women’s Record House has also come to the fore as a result of my doctoral research. Moreover, thanks to People’s History Museum (PHM), Rose’s story is receiving further interest as a suffragette tea set, that once belonged to Rose, is now on display at the museum until Sunday 24 February 2019 as part of their programme exploring the past, present and future of representation, marking 100 years since the passing of the Representation of the People Act (1918).

The tea set, now in PHM’s collection, includes the Angel of Freedom design created by Sylvia Pankhurst. It was in my home town of Stoke-on-Trent that the tea sets were originally made by H W Williamson of Longton. Rose Lamartine Yates regularly held fundraising tea parties for the Wimbledon WSPU in the gardens of her home, Dorset Hall in Wimbledon and the Lamartine Yates family would have had multiple suffragette tea sets in their home during the height of the campaign for women’s suffrage.

For more information on suffragette china please see this article by Elizabeth Crawford.

The early years

Rose Emma Janau was born of French parentage on 23 February 1875 at 33 Dalyell Road in Lambeth, London and was the youngest of three children.[1] Both her parents, Elphege Bertoni Victor Janau (b 1847), a teacher of foreign languages, and Marie Pauline Janau (b 1841) were born in France but later became naturalised British citizens. Rose was schooled at Clapham and Truro High Schools and travelled to Kassel and the Sorbonne to study at the University of Paris.[2] In October 1896, Rose entered Royal Holloway College to study Modern Languages and Philology. In 1899, Rose passed the Oxford Final Honours Examination (the highest examination that was open to women at the University of Oxford) however she was not awarded her degree on the grounds that she was simply a woman.[3]

In 1898, with the full approval of her parents, Rose began a courtship with solicitor and family friend, Thomas (Tom) Lamartine Yates. The couple married in 1900 in Stoke d’Abernon in Surrey. During their first years of marriage, they were both passionate cyclists who toured throughout Europe with the Cyclist’s Touring Club (CTC).[4] Rose became a leading figure within the reform party, becoming the first female member to be elected to the CTC’s council in 1907. It was during this time, when Rose stood for election to the CTC’s council, that she made the statement that she ‘was not a suffragette’.[5] Nevertheless, just a year later, Rose wrote that although it was ‘an honest statement’ it was at the same time ‘untrue’.[6] She stated ‘for looking into the matter seriously I find I have never been anything else, therefore, I never really became a suffragist, I was born one and the tale I have to tell is rather how I came to realise I was and must remain one at whatever the personal cost’.[7]

The suffrage years

Rose joined the Wimbledon branch of the WSPU soon after it was founded in January 1909 and immediately became a member of the committee. However, it was February 1909 that was said, by Mary Leigh, to be the date that ‘a new life was to open out for Rose’, as it was on 22 February 1909 (the eve of Rose’s 34th birthday) that she attended a public meeting held in Wimbledon where Christabel Pankhurst was the chief speaker.[8] During the meeting, Rose felt a ‘definite call’ and when she arrived home from the meeting, together with Tom she wrote the telegram offering her services to the WSPU for the next deputation.

On 24 February 1909, Rose attended a deputation, led by Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, from Caxton Hall to the House of Commons, to present a petition under the Bill of Rights to the Prime Minister Herbert Asquith.[9] However, Rose was seized by police officers when she attempted to deliver the petition and was subsequently arrested along with 28 other women and charged with ‘obstructing the police in the execution of their duty’.[10] Despite her husband acting for her defence, she received one month’s imprisonment in Holloway prison. Her son Paul was just eight months old at the time of her imprisonment and the satirical magazine Punch printed a set of verses criticising her for leaving him. Rose defended her decision on leaving Paul not just in her court hearing but also in various speeches that she gave on her prison experience, stating that he was left in the care of her husband, a nurse and ‘the gardener’s capable wife’.[11] On her return to Wimbledon, Rose’s house had been decorated in the colours of the WSPU to mark the occasion and at the end of April 1909, Rose was awarded the new illuminated addresses (given to all WSPU members who had served at least one week’s imprisonment) and a Holloway Prison brooch.[12]

On her return from prison Rose continued as an active member of the Wimbledon WSPU and by the end of 1909 she had replaced Margaret Grant as the Wimbledon WSPU’s Honorary Organising Secretary. When Rose took on this position within the local Union, she essentially became an unpaid, full time worker for the WSPU. In her capacity as Honorary Organising Secretary she organised and addressed local meetings, oversaw management of the local WSPU shop, enrolled new members, organised local suffragette bazaars and garden fetes, contributed weekly reports to the local, national and suffrage press, and most famously defended women’s right to free speech on Wimbledon Common, speaking there at 3.00pm every Sunday on women’s issues. Rose not only became the face of the Wimbledon suffrage campaign, she was also the driving force behind the local movement and was the key to its success.[13] Between 1909 and 1911, Rose, along with other Wimbledon volunteers, increased the turnover for the Wimbledon WSPU by over 1000%; their annual turnover rising from £23 in 1909 to £328 in 1911.

In addition to all her commitments as Wimbledon WSPU’s Honorary Organising Secretary, Rose also opened up her Wimbledon home, Dorset Hall, to suffrage activists who were in need of recuperation from their exhausting daily schedules. The most notable suffragettes to have stayed are Emily Wilding Davison, Mary Leigh and Mary Gawthorpe. WSPU organiser, Mary Gawthorpe, actually stayed with the Lamartine Yates family for six months from October 1910 whilst recuperating from a condition Mary described as ‘overstrain and injury received in the votes for women campaign’.[14]

Nevertheless, it wasn’t just suffragettes that Rose and Tom welcomed into their home. In 1913 Rose was the ‘first guard of honour’ to Emily Wilding Davison’s coffin, and opened up her house to Emily’s brother, Captain Davison, during the inquest and the funeral. Their generosity to the Davison family is apparent in a letter that the Captain wrote to Tom, thanking them for their kindness and support with the funeral and inquest (Tom was the solicitor who represented the Davison family at the inquest). After Emily’s funeral Rose took nearly a year off from the Wimbledon WSPU due to a ‘severe illness.’ [15] After several attempts to recover from her illness in ‘the fray’, she was ‘ordered abroad for rest.’[16] During this time the Wimbledon WSPU was organised by the Union’s second in command, Edith Begbie.

Women’s suffrage and World War I

By the summer of 1914, Rose had returned as Honorary Organising Secretary of the Wimbledon WSPU but soon afterwards war was declared. WSPU members were informed of the ‘temporary suspension of militant activity until the conflict was over’.[17] The Pankhurst leadership argued that to secure votes for women they needed a ‘national victory’ since ‘what would be the good of a vote without a country to vote in!’.[18] However, Rose and the Wimbledon WSPU didn’t agree with this decision. In their local 1914 annual report, they record that ‘the subject of women’s enfranchisement was still a concern for many local women’ and because of this, the branch chose to ‘keep in touch with the only subject which unites all suffragists’ by holding weekly meetings, readings and discussions at 3.00pm on Saturday afternoons. This was open to ‘members and their friends’.[19] This continuance of suffragette meetings by the Wimbledon WSPU into 1915 is highly significant as they were the only local WSPU branch that is known to have defied instruction and continue their local meetings. Not only did they continue their meetings but in September 1914, Rose tried to minimise the suffering brought upon women and children in the locality by reason of the war by persuading the WSPU committee to transform the bottom floor of their WSPU shop into a cost-price restaurant. In just one year the restaurant served over 40,000 meals.

With the restaurant a success, Rose turned her attention onto what she felt was the most pressing issue at this time. In 1915, this was still votes for women. Rose and many other women such as Mary Leigh, Dorothy Evans and Annie Cobden Sanderson were all united in their disapproval of the WSPU leadership’s decision to no longer use the WSPU’s name, and its platform, to campaign for women’s suffrage.[20] Consequently, on 5 December 1915, Rose and the temporary executive proceeded to devote themselves to suffrage work and acted ‘untidily as a group of the WSPU for suffrage only’.

‘The Suffragettes of the WSPU’, as the organisation became known, resumed ‘the highly important social and political work of the WSPU’.[21] Meetings of the Suffragettes of the Women’s Social and Political Union (SWSPU) took place at least once a week throughout 1916 and 1917 and the SWSPU newsletter, The Suffragette News Sheet, was sold on the streets of London. The SWSPU also contributed to the wartime campaign for women’s enfranchisement by signing circular letters to parliament, attending pickets at the House of Commons and taking part in collective deputations to parliament with organisations such as the East London Federation of Suffragettes, the United Suffragists, and the Women’s Freedom League.

Life after votes for women

On 6 February 1918, the Representation of the People Act received Royal Assent, giving the vote to some women over the age of 30 who met a property qualification and to all men over the age of 21. With votes for some women achieved, Rose’s focus altered. With the support of the National Federation of Women Teachers, she was elected in 1919 to the London County Council (LCC). Rose’s election to the LCC provided her with a platform on which she, as a practical woman and mother, could use her voice and influence to help improve the lives of women and children in North Lambeth by shaping the local political agenda and ensuring that local women and children were a priority. Whilst serving on the LCC, Rose worked tirelessly to improve the living conditions of North Lambeth residents, suggesting and implementing house plans that would benefit housewives and working women. She also ‘persistently supported every effort to improve the tram service and reduce the fares’ notably securing the halfpenny fare for children in her constituency. Moreover, her work for equal treatment of women regarding their wages was tireless, and in 1920 she secured a LCC grant which enabled a minor ailment children’s centre to be opened in North Lambeth in 1921, named The Rose Lamartine Yates Clinic. The clinic remained an integral part of North Lambeth’s health care system up until 1958 when it was closed and offered to the National Health Service. Although Rose only served on the LCC until 1922, she remained as the Honorary Treasurer of the clinic until 1934.

In 1938 Rose was one of the prime movers behind the establishment of The Women’s Record House at 6 Great Smith Street in Westminster, London, which she opened in May 1939. It housed a vast range of suffragette material from banners to postcards. Each room had its own theme: the early beginnings of the movement, the militant phase, prison records, souvenirs and reminiscences.[22] However, the existence of the Women’s Record House was short-lived, as it had to close in September 1939 ‘on account of the war’.[23] The ‘suffrage records were distributed to places of safety’.[24] The records that Rose contributed to the collection were taken back to her house for safekeeping and it appears that she never returned them as there is comparatively little that relates to her, or the Wimbledon WSPU, within The Suffragette Fellowship Collection at the Museum of London today.

After the establishment of the Record House, Rose was never again active in public life. Instead, she settled in her flat in Putney, London, and ‘delighted in her grandchildren’- whom she adored. In 1951, she bought her son a house in Sevenoaks, Kent and ‘visited frequently’.[25] Just three years later, after a brief illness, she died of colon cancer at the age of 79. She was buried next to her beloved husband, Tom, in the family’s plot in St Matthew Avenue, Brookwood Cemetery.[26]

Dr Alexandra Hughes-Johnson is a historian of 19th and 20th century Britain with a particular interest in women, gender, health and political activism. Alexandra recently completed her PhD at Royal Holloway University. Her thesis is entitled ‘Reconfiguring Suffragette History from the Local to the National: Rose Lamartine Yates and the Wimbledon WSPU’. Alexandra is currently working on a journal article which focuses on the establishment of various wartime suffrage organisations and a book proposal for her first monograph.

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM.

People’s History Museum is open seven days a week from 10.00am to 5.00pm, Radical Lates are on the second Thursday each month, open until 8.00pm. The museum is free to enter with a suggested donation of £5. Represent! Voices 100 Years On is a Family Friendly exhibition that runs until 3 February 2019. Find out about visiting the museum, and check out what’s on.

PHM’s archive: the museum’s archive holds Emily Wilding Davison’s funeral service programme, 1913. The funeral programme includes a short obituary, a list of hymns and an emotional piece on her ultimate sacrifice for women’s suffrage. Find out more about visiting the Labour History Archive & Study Centre.

[1] Please note that some of the material used in this blog post was originally published in Women’s History, 2:1 (2018), 19-26.

[2] A.J.R., eds, The Suffrage Annual and Women’s Who’s Who, (London: Stanley Paul & CO, 1913).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Gail Cameron, Rose Lamartine Yates (1875–1954), ODNB.

[5] Elizabeth Crawford, The Women’s Suffrage Movement, A Reference Guide, 1866-1928 (London Routledge, 2001), 763.

[6] Lamartine Yates, Rose How I Became a Suffragist, Women’s Library, Papers of RLY (7RLY).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Leigh, Mary, Biography of Rose Lamartine Yates, date unknown. Typescript Biography. From Women’s Library at LSE, papers of Mary Leigh, MLB/E

[9] Lamartine Yates, Rose. A Month in the Common Gaol for the Faith. Women’s Library, Papers of RLY (7RLY).

[10] Ibid.

[11] Leigh, Mary, Biography of Rose Lamartine Yates.

[12] Crawford, The Women’s Suffrage Movement, 763.

[13] Itinerant organisers are paid organisers who travelled throughout the country to organise for the WSPU. Unlike district organisers, they did not have a fixed area that they focused upon. – not clear how this note relates to where it’s linked to above – perhaps should come after ‘unpaid’ mention?

[14] Mary Gawthorpe Fund Letter, Dora Marsden Collection, Box 2, Folders 1-2; Source quoted in L. Meredith, Mary Gawthorpe’s post-WSPU career, 2011

[15] Leigh Mary, Biography of Rose Lamartine Yates.

[16] Leigh Mary, Biography of Rose Lamartine Yates.

[17] June Purvis, The Pankhursts and the Great War, in The Women’s Movement in Wartime: International Perspectives, 1914-1919, ed. Alison Fell and Ingrid Sharp. (Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 143.

[18] Pankhurst, Unshackled, 288.

[19] The Wimbledon Boro News, Wimbledon WSPU Annual Meeting, March 13, 1915, 6.

[20] The Vote. A Protest Meeting. November 5, 807, 1915.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Lamartine Yates, Paul. Paul Lamartine Yates’ autobiography from the John Innes Society, Wimbledon.

[23] Suffragette Fellowship Newsletter. Women’s Record House. 1939-40. From The British Library.

[24] Suffragette Fellowship Newsletter. Women’s Record House. 1939-40. From The British Library.

[25] Lamartine Yates, Paul. Paul Lamartine Yates’ autobiography.

[26] Lamartine Yates, Paul. Paul Lamartine Yates’ autobiography.