PHM’s former Collections Manager, Sam Jenkins, studied History and wrote her dissertation on anti-fascism, so she’s was the perfect person to turn to find out more about the Spanish Civil War; the links that are made to World War II, Britain’s role within it, and the legacy that it would create. Here Sam shares an insight into the events surrounding the bloodiest conflict seen in Europe since the end of World War I, and some of the stories that are told through the museum’s collection.

The Spanish Civil War took place between 1936 and 1939; a time preceded by great divisions across all of Europe, that had deepened in Spain after a long period of decline following the collapse of the Spanish Empire. It began as a military revolt on 18 July 1936, with right-wing officers in Morocco taking arms against the Republican Popular Front government. Within days it had spread to mainland Spain, with control gained over much of northern Spain and a number of key southern cities. However, the coup failed to gain the whole country and a bloody civil war unfolded. Those supporting the coup were known as the Nationalists and received aid from both Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany.

The Spanish Civil War was the first real clash between fascists and anti-fascists at this level. It shows a boiling over of fractional attitudes and proved that something would happen with these rising fascist states.

In many ways it was also a testing ground for the fascist powers. Hitler and Mussolini supported Franco, especially by providing arms and aircraft, and they were able to see that the democratic powers in Europe (and America) wouldn’t intervene. The signing of the Non-Intervention Agreement, and, possibly more importantly, France and the UK keeping to the agreement even when Germany and Italy weren’t, was key to showing Hitler that they really didn’t want war; that they would do almost anything to avoid another large conflict. This was, of course, also born out through the appeasement policy that Britain followed in the late 30s.

The Spanish Civil War also saw the creation of systems that were used or emulated in World War II. The Communist Party were central to helping volunteers get from Britain (and various other countries) to Spain. These systems, and often the routes volunteers were sent along, were then reused during the war by resistance groups. In fact, routes across the Pyrenees that had been used to get people into Spain, were then used to get refugees out of Spain, and then used to get people back into Spain and to Portugal during the war.

Many people who fought in Spain ended up volunteering to fight for Britain or, such as in France, working in resistance networks, where guerrilla tactics were used like in Spain.

In lots of ways, it was almost a practice ground for the coming conflict.

Those who chose to fight – whether they were Communists, Socialists, Trade Unionists, or left leaning writers and journalists – were all in the position of seeing the growth of fascism and wanting to stop it.

Around the same time as the Spanish Civil War was raging, Oswald Moseley’s British Union of Fascists were marching and holding meetings in predominantly Jewish areas – the Battle of Cable Street happened in 1936 and that actually spurred many people to go and fight in Spain – they saw in Spain the risk of allowing fascism to spread unchecked. For them, fighting in Spain was about stopping that advance, which is seen in many of the popular phrases surrounding the Spanish Civil War: ‘no pasarán’; ’this far and no further’; and, the very famous, ‘if you tolerate this, then your children will be next’.

In a very European context, fighting in Spain was about defending Britain, because these men and women truly thought that this was the only way to defend Britain (and the rest of Europe) from the danger of fascism. But I really think that the heart of it, the most basic reason for men and women signing up, can be found in the poem The Volunteer by Cecil Day Lewis: ‘We came because our open eyes could see no other way’.

In our collections, we have several objects from two particular prominent men who volunteered: Jack Jones and Bob Edwards.

Jack Jones was born in Liverpool and became a docker in the 1930s; he was a socialist and Trade Unionist (a member of the Transport and General Workers Union), and an active anti-fascist, organising protests against British Union of Fascist meetings being held in Liverpool. He volunteered to fight in Spain in 1936, right at the start of the war, bringing quite a lot of experience from his previous two years in the Territorial Army. He fought in Spain with the British Battalion of the International Brigades, until he was wounded at the Battle of the Ebro in 1938.

Bob Edwards was also from Liverpool, to docker parents, but is mostly known for his political career. He became a Labour councillor in 1927, at the age of just 22, and had quite a leftist life from that point: he travelled to the Soviet Union with an Independent Labour Party Youth Delegation, and met both Stalin and Trotsky, and worked as a messenger for the Trades Union Congress during the General Strike in 1926. So, as with Jones, there was a socialist background to his involvement in the Spanish Civil War and, again, he got involved very early on.

In 1936, Edwards delivered an ambulance to the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification (POUM) and, in 1937, would travel to Spain again to fight with the POUM militia – the same militia that Orwell served with. This was as part of a group of around 25 men sent by the Independent Labour Party (ILP) to fight in Spain, which Bob Edwards actually led. While there were more volunteers for the ILP, they chose to only send unmarried men, sending the initial 25 men, and planning to send more afterwards; but, shortly after the first group left, the British government decided that they would prosecute anyone going to fight in Spain and the ILP backed down from recruiting volunteers.

But we also have smaller collections or individual items from others who volunteered to fight or supported the campaign in Spain, including Thomas Mitchell, Fred Pearson, and Steve Yates.

The British response was quite mixed, between different political views and also between the government and the people.

The British Government decided on a policy of non-intervention, which meant that not only would they not send their military to help, but they also wouldn’t provide financial aid or arms to the Republican government. There are quite a few different theories for why this was: whether the government thought that supporting the Republicans would start the large Europe-wide war they wanted desperately to avoid; because the government believed Germany and Italy to be more powerful and war-ready than they really were; or whether it was the strong anti-Communist sentiment that led the government to be reluctant to support the highly Communist Republican forces. Whatever the reason, Britain officially did not lend any support to either side of the conflict. The small concession by the British government was to allow the placement of refugee children (known as Basque refugees, though some were from non-Basque regions) in Britain for the duration of the war.

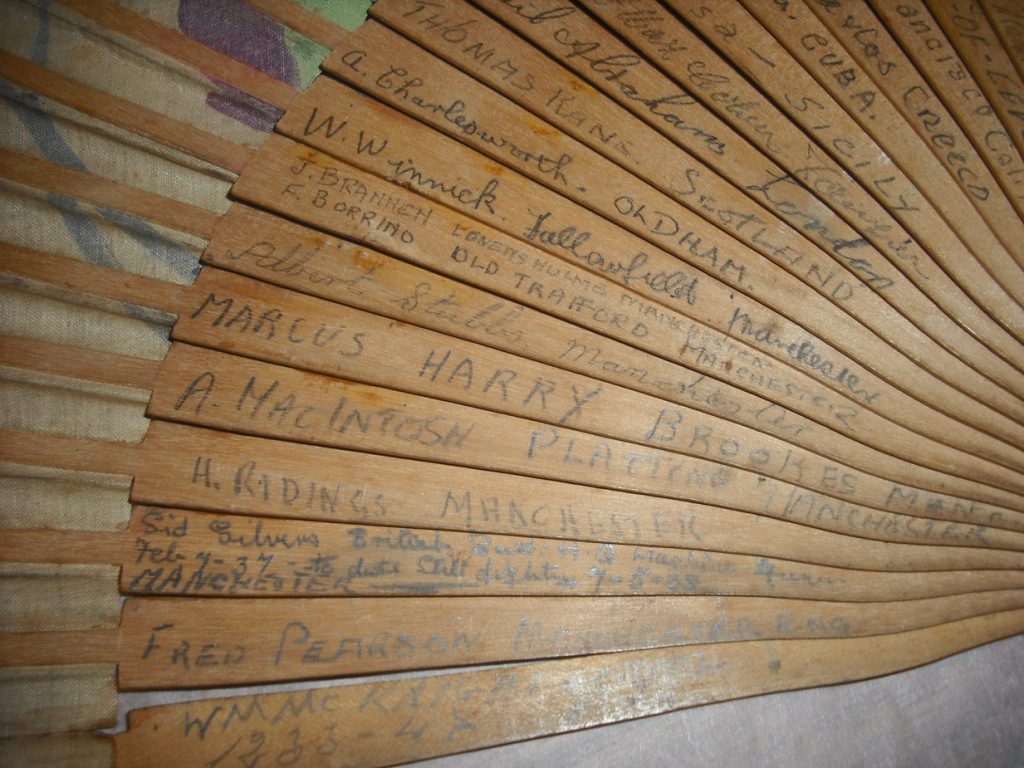

Meanwhile, many members of the public had a completely different response – on either side. The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was very active in Britain at the time, many Catholic intellectuals supported the pro-Catholic ‘Nationalist’ forces, and some Britons even travelled to Spain to support Franco’s forces. But far more would travel to Spain to fight for the Republican cause; around 5,000 men made the illegal journey to fight in the International Brigades. These Brigades were really a hodgepodge of different nationalities – while there was, eventually, a British Battalion, this included those from Britain, Ireland and British dominions. We’ve got a lovely fan in the collection that’s signed by men from the International Brigade, and many of them put where they were from next to their name – there’s Manchester and Scotland, but also the USA, Sicily and Cuba. It really shows that these men were fighting a truly international war with comrades from countries they’d be unlikely to ever visit.

In addition to the men who volunteered, there were also women who volunteered to fight or provide medical aid and, of course, those who supported the cause without going over to Spain. These people raised money for the Republican forces to buy arms, or to provide food and medicines. This was often organised through Trade Unions, and we have several banners from the Printers Union highlighting not only their support for the Republican’s, but the amount of money they provided as well. We also have some absolutely magnificent posters discovered in our collection that are hand-drawn, encouraging support for the Republican cause – we think by a member of the Communist Party. We don’t know exactly who made them, or where they were used, but they really show that, even if people didn’t volunteer, they still pushed to support the fight against Franco’s fascism.

What all of these different responses really show is how complicated the political landscape was at the time – the tension between the far-right and the far-left was building and people often had very polarised views about what should be done. It was a bit like Brexit is today – almost everyone had an opinion and those opinions often clashed. And even if you didn’t have a direct opinion, the results would probably affect you in one way or another. There’s also, of course, the large elephant in the room that was World War I, which was still in fairly recent memory for a lot of the population. The government, especially, wanted to avoid another all-out war in Europe, and many people, especially those who had lived through the war, approved of appeasement and non-intervention as a way to avoid another conflict.

Many of the more famous volunteers were from the middle class, like academics, authors and poets H. Auden or George Orwell (who was upper-middle class at the least) but the vast majority of those who volunteered for the International Brigades, and those who undertook a lot of the fundraising efforts were from the working class.

Volunteering for the International Brigade, especially, was far more common in the industrial heartlands – the coal mines of South Wales, London, Liverpool, Manchester and Glasgow. Part of this was the drive from the Trade Union movement and the Communist Party to support Republican Spain, both of which were far more popular among the working class. The Communist Party was largely responsible for helping volunteers get over to Spain in the first place, with the connected organisation in different parties playing a big part in how they could illicitly get men from the UK to the Spanish border.

Left-leaning journalists and writers did take up the cause, but the vast drive of the British response was from the working class, from volunteers going over to fight or provide medical support, and from donations to help provide food, aid, and money to buy arms.

You can read more about the impact and legacy of the Spanish Civil War in an article written by journalist Fiona Keating for her article published in Britain at War magazine and KeyMilitary.com, in which Sam Jenkins was one of those interviewed for the piece.

Material on the Spanish Civil War, much of it archival, forms one of the most extensive and interesting collections in Salford’s Working Class Movement Library (WCML). The Spanish Civil War collection at WCML contains books, pamphlets, artefacts and tape recordings, and the archival material includes an impressive archive of letters written by men from the Greater Manchester area who went to fight in Spain.

Read former PHM Visitor Services and Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU) post graduate student Beth Lane’s blog Orwell & Edwards: conflict & candid moments sharing insight from previously unseen Spanish Civil War photographs in PHM’s internationally significant collection.

The museum’s collection includes items of national importance from the last 250 years of British social and political history. It is home to the complete holdings of the national Labour Party and Communist Party of Great Britain and over 95,000 photographs relating to the growth of democracy in Britain, covering not only parliamentary reform, extension of the vote and general elections, but grassroots organisations and campaigns also.

The archive is open Wednesday to Friday 10.00am – 4.00pm, lunchtime closure 12.30pm to 1.30pm

Email archive@phm.org.uk to book an appointment

People’s History Museum (PHM) is open 10.00am to 5.00pm, every day except Tuesdays and entry is free with a suggested donation of £10.

An earlier version of this blog was first published on 17 July 2021