To celebrate International Women’s Day, we’ve invited our former colleague and the National Trust’s new Programme Curator of National Public Programmes Helen Antrobus to blog for us.

Helen is a specialist in the history and collections relating to 20th century radical women; from the women who marched at Peterloo, to the female Chartists; those involved with the women’s suffrage movement, to the first female MPs, and shares with us her insight into the women at Peterloo.

‘On 16 August 1819, around 60,000 people gathered in St Peter’s Fields in Manchester. Henry ‘Orator’ Hunt had been invited to speak at a meeting to challenge the Anti-Corn Laws, which kept the price of wheat artificially high, and to advocate parliamentary reform. Manchester, which had boomed during the Industrial Revolution, did not have its own Member of Parliament (MP), and therefore the cotton and textile workers who dominated the city were not being politically represented.

The reformers were demanding the vote for men, pre-empting Chartist action that would come about 20 years later. Although votes for women were not included in reformers’ demands, roughly one in eight of those at St Peter’s Fields that day were women. In their best clothes and bringing their families with them, with their children in their arms. Later, in the court testaments, some of the women argued that they knew it would not be a riot, simply because they felt safe enough bringing their children along.

The meeting ended as a massacre. Around 18 people died, and hundreds of people were injured as the yeomanry charged the crowds, who fled the field, crushing each other to escape the sabres of the volunteer militia. Included in the list of dead were Margaret Downes, Mary Heyes, and Martha Partington.

The women who attended St Peter’s Fields that day were not only on the ground, but standing on the speakers’ platform alongside the men. Mary Fildes, the president of the Manchester Female Reform Society (and PHM Radical), can be seen in depictions of the day, holding a banner with the cap of liberty on the pole.

The Peterloo Massacre was not the first instance of women being politically engaged. In 1784, the Duchess of Devonshire Georgiana Cavendish campaigned for Charles Fox to win the general election, for the Whig party over the Tories. She wore a fox tail in her hat, and spoke next to him at rallies which resulted in rumours that she was buying votes for kisses.

In 1792, Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman was published, and though it argued for educational advancement for women, Wollstonecraft was strongly criticised for her views. Both she and her partner William Godwin disagreed with marriage, and she subsequently had two children outside of wedlock by two different men. This was frowned upon, and fed into the idea that political women usurped traditional gender roles, and distracted women from their children and caring for their families.

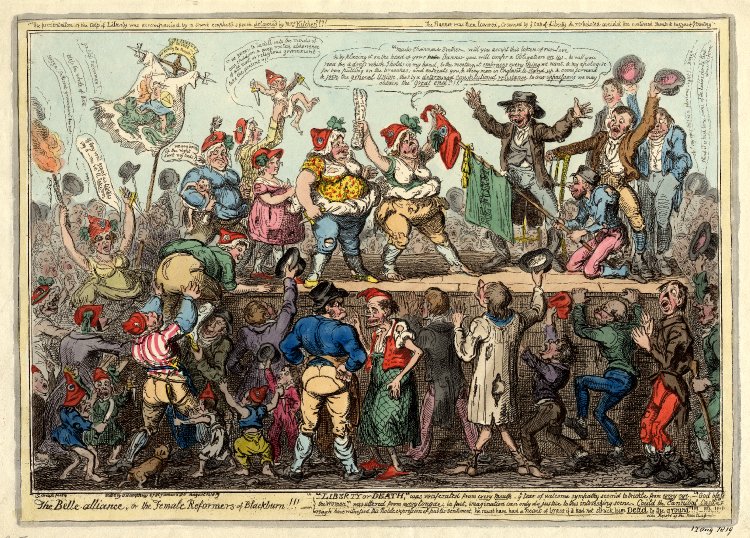

Four days before the Peterloo Massacre, a cartoon entitled The Belle-alliance, or the female reformers of Blackburn!! was published, depicting the Blackburn Female Reform Society speaking at an open air meeting. Despite the women being well organised and sober, the cartoon depicts them as bawdy, licentious, and ugly women; their children lay abandoned, their clothes are dishevelled, and the drawing is peppered with sexual innuendo, implying that women who got involved with politics were merely looking for sexual favours.

The argument of the Female Reform Societies, however, was sound. Though they did not demand the vote for themselves, they recognised the impact of having a household member – their husbands and fathers – being able to vote would make a massive difference on matters such as income, wages, and working conditions.

Like many of the women who attended that day, Mary Fildes wore her best clothes. When the yeomanry attacked, Mary attempted to escape, but was caught when her dress caught on a nail on the speakers’ platform. Mary was attacked by the yeomanry, but survived. Another woman, Elizabeth Gaunt, was found in Henry Hunt’s carriage, perhaps shielding herself from attack. She, alongside Hunt, was put on trial for treason.

The dresses of the women at Peterloo, as Mary’s experience highlights, were both emotionally and physically restricting; not only did they delay escape, but they marked out political women, the usurpers of society, for attack. One of the few surviving objects from that day at St Peter’s Field is a dress worn by a Mrs Mabbott – a shopkeeper who resided on Bridge Street in the city centre of Manchester. The dress is constricting; it doesn’t allow for much movement, and demonstrates how difficult it would have been for women to flee that day. Although there were less women present at Peterloo in comparison to the number of men, when examining the figures, it is clear that a high percentage of women were attacked and injured; whether through convenience, or design.

The dresses of the women at Peterloo, as Mary’s experience highlights, were both emotionally and physically restricting; not only did they delay escape, but they marked out political women, the usurpers of society, for attack. One of the few surviving objects from that day at St Peter’s Field is a dress worn by a Mrs Mabbott – a shopkeeper who resided on Bridge Street in the city centre of Manchester. The dress is constricting; it doesn’t allow for much movement, and demonstrates how difficult it would have been for women to flee that day. Although there were less women present at Peterloo in comparison to the number of men, when examining the figures, it is clear that a high percentage of women were attacked and injured; whether through convenience, or design.

What is clear is the immense bravery of the women who marched to St Peter’s Field that day. Not only did they risk the wrath of the magistrates and the law-makers, but they risked anger amongst their own ranks as well. To be a political woman took courage, and the women of Peterloo would go on to champion Chartism, the abolition of slavery, and eventually, women’s suffrage. At each step, they would face more backlash and outcry; even when their dresses were less restrictive, and their voices grew louder, women were kept out of parliament, fighting to get in. It is incredible to think that it took another 109 years of persistence and perseverance for the true meaning of universal suffrage – a demand carried on banners at Peterloo – to be achieved.

It is no surprise, then, that almost a century later, a suffragette stood at a husting in the centre of Manchester, and addressed the crowds of men and women as such:

‘We helped you carry your banners at Peterloo. Now it is your turn to help us carry ours.’’

Mrs Mabbott’s dress, on loan from Manchester Art Gallery was on display in the Disrupt? Peterloo and Protest exhibition at PHM from Saturday 23 March 2019 until Sunday 23 February 2020 as part of PHM’s year long programme exploring the past, present and future of protest, marking 200 years since the Peterloo Massacre; a major event in Manchester’s history, and a defining moment for Britain’s democracy. The exhibition Disrupt? Peterloo and Protest was supported by The National Lottery Heritage Fund.

People’s History Museum is open every day except Tuesday from 10.00am to 5.00pm, and is free to enter, most visitors pay £10.

Teach about Peterloo with a learning resource and book a self guided visit for your learning group to explore further.