2024 marks the 40th anniversary of Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM), which formed in the early months of the 1984 to 1985 Miners’ Strike. Joining us to explore this historical moment and the legacy that it created is People’s History Museum’s (PHM) Collections Assistant Jaime Starr.

In this first of two blogs Jaime will discuss how LGSM formed and how events unfolded 40 years ago; dispelling some myths along the way.

Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) was an LGBTQIA+ activist group founded in London in July 1984 after founding members, Oldham born Northern Irish raised Mark Ashton and Accrington born Mike Jackson, attended a talk by a striking miner that inspired them to take collection buckets to London Gay Pride in June 1984.

LGSM were active for the remainder of the 1984 to 1985 Miners’ Strike, with autonomous branches setting up in Manchester, Dublin, Glasgow, and more. Their main goal was to raise money to support the miners and their families, as many were experiencing financial hardship while they were out on strike.

Many LGSM members were active in leftwing and socialist political activism. Mark Ashton was the General Secretary of the Young Communist League and Nigel Young co-founded the Gay Liberation Front. The political belief of many LGSM members was that solidarity between all working class people was important – that if the Thatcher government broke the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), the whole working class would be worse off, no matter their sexuality.

While politics was a main driving force for many members, some saw LGSM as a way to connect to community, like Jonathan Blake who had become socially isolated after becoming one of the first people in the UK to be diagnosed with HIV.

Beyond class solidarity, LGSM saw parallels between the vilification that the NUM and LGBTQIA+ people were experiencing from the government and much of the press. At the time, homophobia and transphobia was normalised in British society, increasing in ferocity as the HIV epidemic grew. The fake news that was spread about LGBTQIA+ people at the time made many LGBTQIA+ people less predisposed to believe propaganda about the miners. Some LGBTQIA+ people, like Mike and Gethin Roberts, came from or had family from mining towns. Gethin’s mum came from Neath in Wales, which influenced LGSM’s choice to twin with and donate money to the nearby mining village of Onllwyn.

Others, like Mark Ashton, respected miners for doing difficult and dangerous manual labour jobs they wouldn’t be willing to do themselves. When asked by journalists why LGBTQIA+ people should support the miners when ‘the miners don’t support us’ Mark replied: ‘What do you mean the miners don’t support us? The miners dig coal which creates fuel, which creates electricity. Would you go down a mine and work? […] One of the reasons I support miners is because they go down and do it. I wouldn’t do it!’

LGSM members took collection buckets to LGBTQIA+ venues across London, raising thousands of pounds for the miners to use as they needed, to buy food and other necessities they couldn’t afford while on strike.

They gave out rotas at LGSM committee meetings, the minutes of which are held in PHM’s archive, to keep track of which venues had been visited and how much they had raised where. Collections were also taken in front of the LGBTQIA+ bookshop Gay’s the Word. The police were known to harass collectors, on one occasion arresting LGSM members for their fundraising activities with no legal reason to detain them. Jonathan Blake explained that police would take positions across the road from the bookshop and if the fundraisers stepped over the property line (marked by tiles) for even a minute, the police could arrest them for obstructing the public footpath. This didn’t deter fundraisers, and collections continued throughout the strike, raising enough money to buy a van for the village, which the miners painted with the LGSM pink triangle logo, proud of where the money had come from.

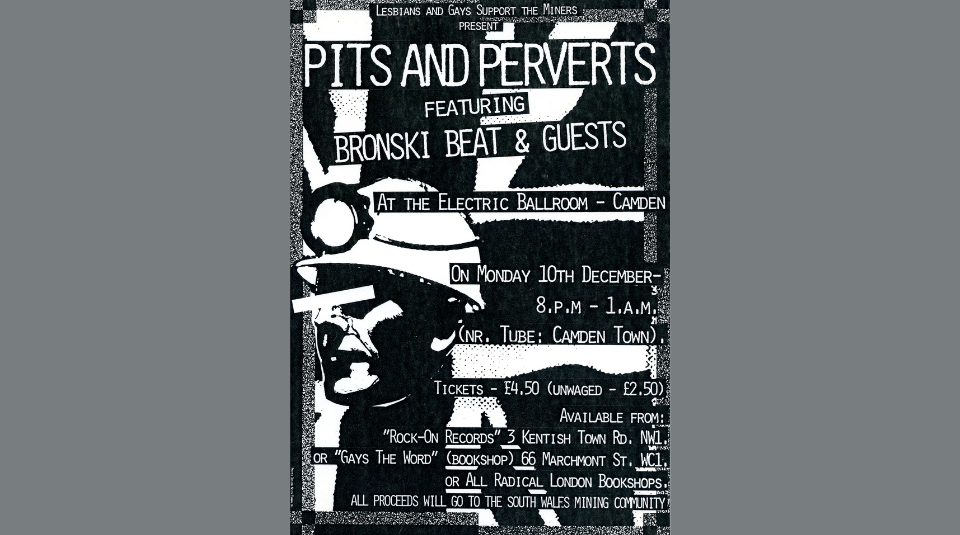

Gay Sweatshop Theatre Company staged benefit performances of Dear Love of Comrades, a play about writer and poet Edward Carpenter, for LGSM. Jonathan Blake designed the now iconic LGSM logo badge, which was printed using funds from Manchester LGSM and sold at Gay’s the Word and Pride events. The biggest fundraising action LGSM undertook was the ‘Pits and Perverts’ benefit concert held at the Electric Ballroom in Camden, London on 10 December 1984, which featured performances by bands like Bronski Beat and raised thousands of pounds for the miners. The gig poster was designed by LGSM member Kevin Franklin.

The idea that working class and rural communities are more homophobic than others is rooted in classism. Even in large cities like London, most LGBTQIA+ people anticipated the risk of experiencing homophobia and transphobia anywhere they went. Some LGSM members had grown up in, and left, pit towns because of bad experiences with homophobia and were unsure how they would be received in Onllwyn. Their worries were unfounded. Mike Jackson said it was like coming home. Until long after the Miners’ Strike, LGSM members didn’t know that the miners held a meeting ahead of their first visit and made it clear that no discriminatory behaviour towards these guests would be tolerated.

On the contrary, families were very keen to host LGSM members. Jonathan remembers being open about being HIV positive with some of the friends he made there and experienced no bigotry or cruelty. Miners and their families visited London and stayed with LGSM members and helped to decorate the Electric Ballroom in Camden for the Pits and Perverts fundraiser night. Solidarity overrode the societally acceptable homophobia of the day.

Following the strike, LGSM members stayed in touch with the Onllwyn community. When Mark Ashton died of an AIDS related illness on 11 February 1987 his funeral was attended by many of the miners. LGSM’s Ray Goodspeed remembers, ‘We had the banners and the band and everything. We marched to the cemetery.’

Miners who worked with groups from the LGBTQIA+ community, like LGSM or Lesbians Against Pit Closures, came away with new understandings of the issues affecting those communities, where before the strike many had never knowingly met an LGBTQIA+ person. Onllwyn miner, Dai Donovan, told the crowds at LGSM’s fundraising Pits and Perverts night: ‘‘You have worn our badge ‘Coal Not Dole’ and you know what harassment means, as we do. Now we will support you. It won’t change overnight, but now a hundred and forty thousand miners know… about Blacks and gays and nuclear disarmament and we will never be the same.’’

The miners committed to supporting their new allies, including rallying to oppose Section 28 legislation which prohibited the discussion of LGBTQIA+ people in schools, colleges, or local government funded institutions like museums. The NUM pushed for LGBT rights to be included in both TUC (Trades Union Congress) and Labour Party policies. Attempts to make these organisations fight for LGBT rights had been made before and it was the NUM’s block voting in favour that made this campaign successful where others had failed. Jonathan Blake directly connects the efforts made by the NUM in these years to the successful passing of the 2004 Civil Partnership Act, showing the kind of lasting power that acts of solidarity can have.

Jaime is an oral historian with a focus on 20th century LGBTQIA+ community activism in the UK and Ireland. Their work has included recording LGSM member Jonathan Blake’s life story for archive, the Giz A Job project documenting oral histories of the 1981 People’s March for Jobs, and their ongoing work on 1980s HIV activism is soon to be presented at the UK Disability History and Heritage Hub conference. At PHM they work to catalogue and care for the museum’s permanent collection, as well as researching the hidden histories of our collection to bring new perspectives to the fore.

An earlier version of this blog was first published in May 2024.