On the anniversary of the 1848 Chartist mass meeting on Kennington Common, London, People’s History Museum’s (PHM) Researcher Dr Shirin Hirsch explores the life of PHM Radical William Cuffay – a ‘scion’ of Africa’s oppressed race – and reveals a precious, rare and poetic treasure of Cuffay’s from the museum’s collection.

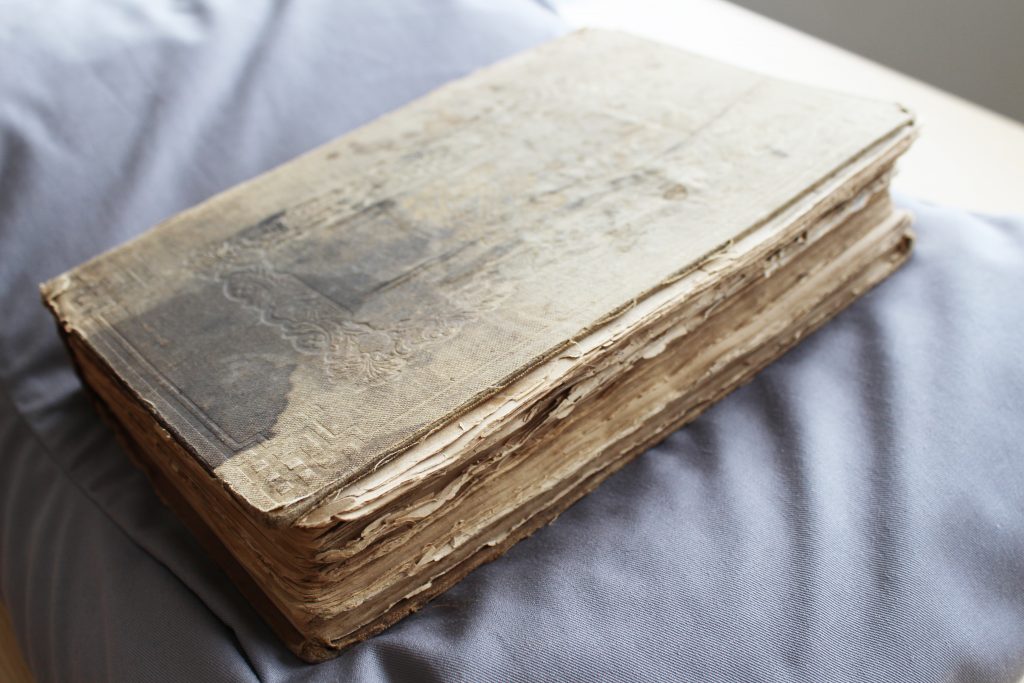

Working class radicals from our past are very rarely remembered within our public sphere – there are few monuments to their feats and their personal collections feature little within the official archives. William Cuffay was one of these working class radicals, preserving no diary, autobiography or papers and his lack of wealth and power leaving only faint traces of his life to explore. Cuffay died a pauper in a workhouse in Tasmania, was buried with no name chiselled into a gravestone, and he had no surviving children (his only daughter died soon after the death of his second wife in childbirth). His homes in London and Tasmania, as well as the workhouse where he died, have long since been demolished. Yet Cuffay’s contributions to the struggles for working class democracy within the British Empire are immense. In this blog I want to think about some of the sources connected to Cuffay, including a precious belonging of Cuffay’s we are honoured to hold at People’s History Museum.

William Cuffay was the descendent of slaves; his grandfather had been sold into slavery from Africa to St Kitts, and his father was born into slavery. Somehow, Cuffay’s father was freed, and he found work as a cook on a warship where he eventually ended up in the dockyard town of Chatham, near London, and married a local. William Cuffay was born in 1788, a boy ‘of a very delicate constitution’, with his spine and shins deformed. Cuffay became a tailor, yet on joining a trade union and participating in a strike he was sacked from a job he had held for many years. In 1839 Cuffay joined the great working class Chartist movement with its national demands for universal male suffrage and democratic change, and before long he had emerged as one of the most prominent leaders of the Chartist movement in London.

1848 was a year in which people took to the streets and revolutions broke out across Europe – it was also a pivotal year for the Chartists in Britain. Cuffay was one of the delegates to the Chartists’ national convention, with their main task to prepare a mass meeting on Kennington Common in Lambeth, south London, that would proceed to march and submit a mass petition to parliament. Cuffay made some of the most radical speeches at this convention and openly denounced the leading Chartists who were more cautious. He was appointed chairman of the committee for managing the procession, responsible for making sure that ‘everything…necessary for conduction of an immense procession with order and regularity had been adopted’. As Cuffay argued, things had now come to a crisis and they must be prepared to act with coolness and responsibility.

In the above early photograph, you can see the crowds meeting on Kennington Common – this is the oldest surviving image of a protest in British history. Although we cannot see Cuffay, the image is a great representation of his collective and organised spirit. Such crowds brought panic to the British state and fears of revolution, so much so that the royal family were sent to the Isle of Wight for their safety. The state used all their power to intimidate and halt the crowd’s march to parliament, declaring the procession illegal and with all government buildings prepared for attack. Even the British Museum was provided with 50 muskets and 100 cutlasses – I’d like to think People’s History Museum would instead have been on the Chartist side, had we existed then! The bridges were sealed off and guarded by thousands of police and soldiers, while steamboats with troops waited on the River Thames nearby. With so much pressure, the Chartist leader Feargus O’Connor agreed to call off the mass procession. As Cuffay noted, the Chartist executive had shrunk from their responsibility.

Angered at this step down, there are unreliable reports from police spies on Cuffay’s involvement with an armed uprising, and on this basis he was tried for ‘sedition’. Cuffay pleaded not guilty and in the court transcripts we can hear how he demanded that, rather than a middle class jury, he had a ‘fair trial by my peers’. Cuffay powerfully stated that the jury ‘were not my equals – I am only a journeyman mechanic’. Reporting on the trial, The Times sneeringly referred to Cuffay and the Chartists as ‘the black man and his party’, going on to describe Cuffay using hideous racism. Cuffay and his two comrades were sentenced to transportation ‘for the term of your natural lives’.

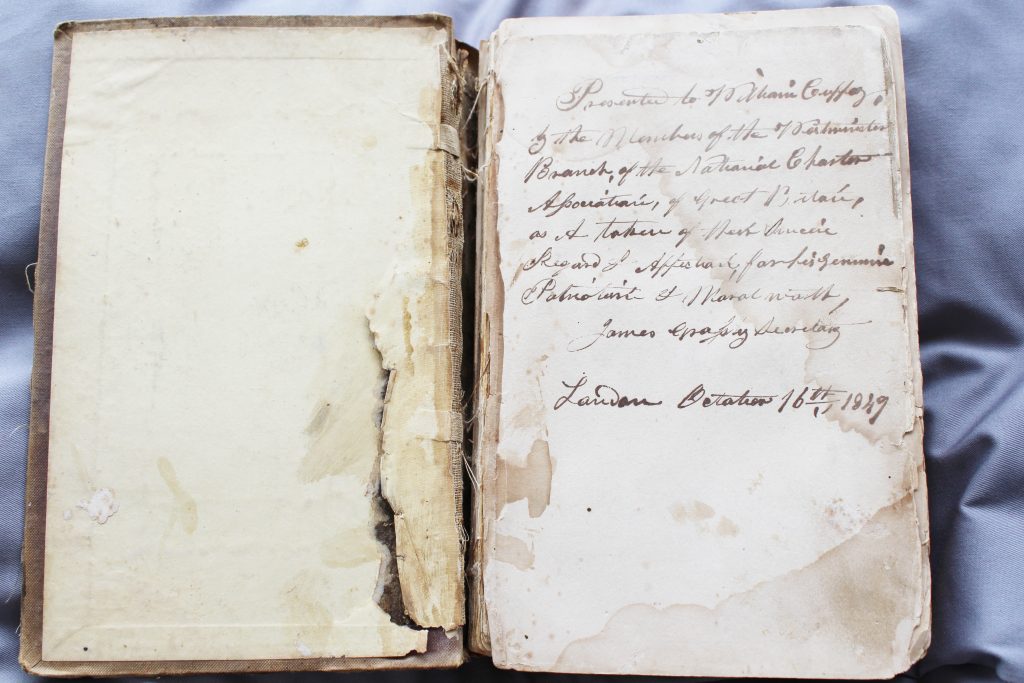

Chartism effectively died at Kennington Common and with the repression that followed, but the networks of solidarity remained. As Cuffay set sail on the prison ship for Tasmania in 1849 he was gifted a beautiful book of Lord Byron’s poetry. On the inside page of the book you can see the handwritten note: ‘Presented to William Cuffay, by the members of the Westminster Branch of the National Charter Association of Great Britain, as a token of their sincere regard and affection for his genuine patriotism and moral worth’.

The book travelled from the docks in Woolwich to the shores of Tasmania, remaining with Cuffay until his death and kept for some years after at the workhouse, before, for some reason travelling to South Africa and then losing any kind of home. It was only because of the work of the Chartist historian Professor Malcolm Chase that the book was saved and donated to People’s History Museum in 2014. What a journey this book has taken, reflecting the twists and turns of this black radical, and the sacrifices Cuffay made for a global cause. Despite Cuffay’s inspirational role, his militancy as well as his black skin and disability, earned him harsh victimisation by the British state. In Cuffay’s speech from the dock, he explained: ‘I have been taunted by the press, and it has tried to smother me with ridicule and it has done everything in its power to crush me’. Perhaps they were angered that Cuffay, a black man drawn from the imperial diaspora to challenge the British Empire at its heart, had been repeatedly elected as their representative by fellow Chartists. Cuffay eventually found himself exiled to another part of the British Empire where he continued to organise and agitate amongst the working poor. His life refused to fit into narrow and nationalistic understandings, but instead pushes us to think of a truly international working class.

It is the words of another Chartist that best sum up Cuffay: ‘loved by his own order, who knew him and appreciated his virtues, ridiculed and denounced by a press that knew him not, and had no sympathy with his class, and banished by a government that feared him…Whilst integrity in the midst of poverty, whilst honour in the midst of temptation are admired and venerated, so long will the name of William Cuffay, a scion of Africa’s oppressed race, be preserved from oblivion’.

Explore Conviction Politics, the Australian-British digital history project exploring the story of radicals and rebels transported as political convicts to Australia.

Keep up to date with PHM’s latest blogs and upcoming events by taking the Radicals quiz to sign up to our regular e-newsletter.

People’s History Museum is the national museum of democracy in Manchester. Entry to the museum is free with a suggested donation of £10. We are open every day except Tuesday, 10.00am to 5.00pm.