After some 30 years in PHM’s store, the Campaign Against the Immigration Laws (CAIL) banner is currently on display for the first time as part of the 2020 – 2021 Banner Exhibition. Whilst the banner may have lain forgotten, its strong message and the reason behind the campaign’s formation have never felt more relevant.

In this blog PHM’s Programme Officer Zofia Kufeldt delves into who CAIL were, the Immigration Act of 1971 which was the impetus behind the campaign and how it continues to form the basis of the UK’s immigration laws today.

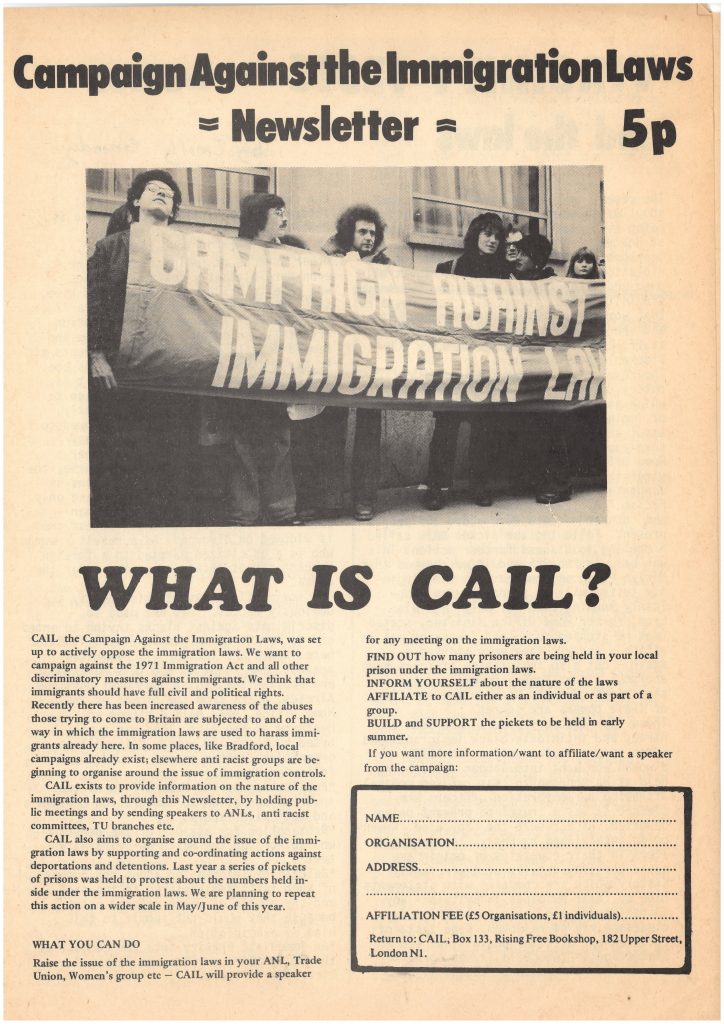

The Campaign Against the Immigration Laws (CAIL) banner was made in 1980. It is over three metres wide and has the words CAMPAIGN AGAINST THE IMMIGRATION LAWS are placed across the full front of the banner.

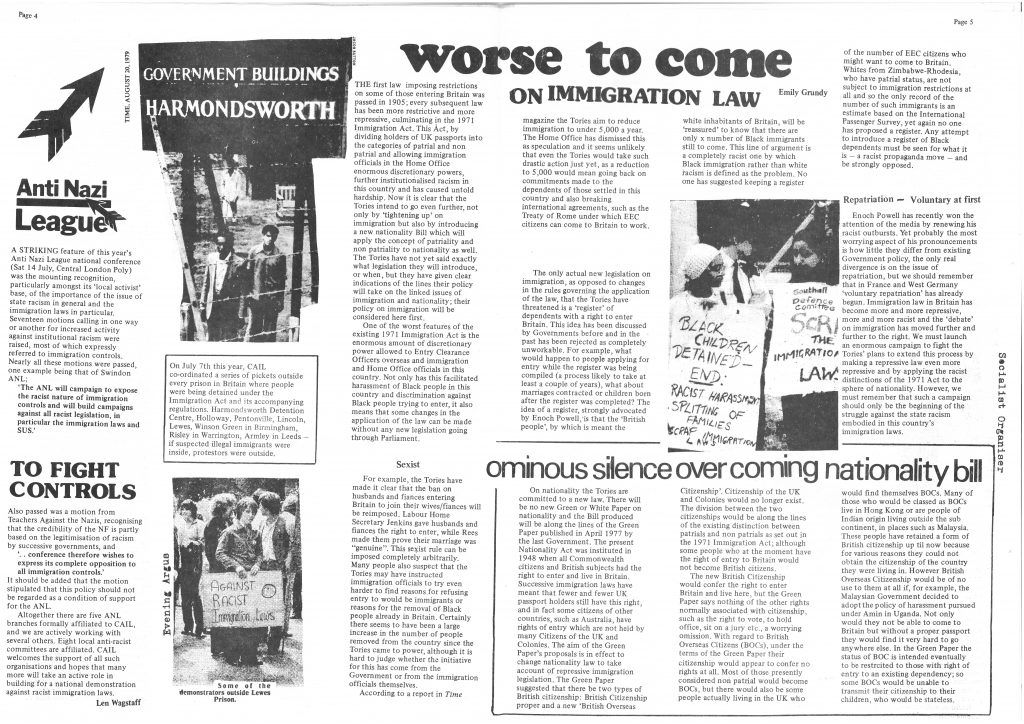

It was used by CAIL in their actions against deportations and detentions, including in a series of pickets of prisons to protest against the number of people held inside under immigration laws – as pictured in their newsletter.

The Campaign Against the Immigration Laws (CAIL) was formed in 1978 by a group who felt the anti-racist movement focused too much on anti-fascism and not enough on tackling state racism. The campaign actively opposed the immigration laws of the time, in particular the Immigration Act 1971, which they believed was the worst example of state racism.

As well as their actions protesting deportations and detentions, CAIL produced newsletters that featured articles on changes in the law, individual immigration cases and anti-deportation campaigns. We have a number of their newsletters at the museum through which we have learnt about the formation of the campaign, its purpose and actions.

The group carefully chose the title Campaign Against the Immigration Laws rather than Campaign Against All Immigration Laws as they wanted to create a unity between those who believed all immigration laws would be racist and those who saw some possibility for reform, but believed some immigration laws were needed. Evidence of this debate in name change was found during conservation work undertaken to allow the banner to go on display for the first time in 2020.

PHM’s Conservator Kloe Rumsey found that two different materials were used to create the lettering on the banner. ‘THE’ is spelled out using paper and glue rather than PVC plastic, which is evidence of the changing name of the campaign. If you look closely, you can see a shadow of the letters ‘ALL’ previously included on the banner.

Around 1981 Campaign Against Racist Laws was formed by the Indian Workers Association. As soon as CAIL realised their aims were the same the group wound up and offered to produce the newsletter for Campaign Against Racist Laws, which they accepted.

The Immigration Act 1971 was a main focus of CAIL’s campaigning. It came into effect on 1 January 1973. The Act was designed to simplify the UK’s immigration laws, building on the Commonwealth Acts of 1962 and 1968. It restricted the entry of Commonwealth citizens to the UK, introduced by the 1945 Labour government, who had previously been encouraged to fill post-war labour shortages.

This concession to Commonwealth citizens with British family connections was racist. Cabinet minutes from the time show that in agreeing to the Immigration Act 1971 ministers knew that their decision to exempt those with a UK-born parent or grandparent would attract criticism for being in favour of the ‘white Commonwealth’, however this racism could be defended on the grounds that Britain had a special relationship with Australia, Canada and New Zealand.[1] This is why CAIL chose the immigration laws to campaign against as the worst example of state racism.

In the years leading up to the Immigration Act 1971, there was negativity and resentment growing towards those migrating to the UK. Immigration in the 1950s and 1960s had increased, and in particular of citizens from the Commonwealth. The British Nationality Act of 1948 had conferred status of British citizenship on all Commonwealth subjects, recognising their right to work and settle in the UK and to bring their families with them.

Enoch Powell, a Conservative Minister during the late 1960s, played an important part in influencing bad feeling towards immigration into the UK. In a speech known as ‘Rivers of Blood’ in 1968, he voiced that many immigrants did not want to integrate and that British people would suffer as a result. He was dismissed from Cabinet, but his speech influenced a lot of anti-immigration and nationalist movements and this issue was brought into the election campaigns of 1970.

In the 1970 general election, Edward Heath and the Conservative Party made a pledge to tackle immigration by introducing a single system to control the number of people arriving in the UK from all countries. When they were elected, they delivered on this promise and passed the Immigration Act 1971.

The Immigration Act 1971 continues to form the basis of the UK’s immigration laws today.

The Act provided protection for Commonwealth citizens if they had lived here for more than five years and if they arrived in the country before 1973, as outlined above, but the onus was now on the individual to prove their right to stay. However, the government gave these people no documents to demonstrate this status. Nor did it keep records. The Windrush scandal, brought to light in 2018, is far from over. There is a huge backlog of cases still to be resolved and the policies which led to this scandal are still in place.

The Act also gave immigration officers the power to detain people seeking asylum in detention centres or prisons while their applications were processed. No time limit was placed on the length of detention or safeguards put in place for those who are detained. To this day, the UK is the only European country that does not have a time limit on detention. It is a breach of human rights and many are calling for a 28 day limit.

Finally, the 1971 Act provides the legal basis for the Home Office to write its own immigration rules. It states ‘The Secretary of State shall from time to time… lay before Parliament statements of the rules… for regulating entry into and stay in the United Kingdom’.[2] In July 2021, the Home Secretary introduced proposals to change the UK’s immigration laws again with the Nationality and Borders Bill.

The Nationality and Borders Bill will make significant changes to the UK’s asylum system and drastically restricts the rights of refugees. The ability to seek asylum is a precious right that belongs to all; a milestone in the history of human rights when it was granted by the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. This Bill will profoundly undermine the UK’s commitment to the 1951 Refugee Convention by creating a two tier asylum system that will criminalise those who arrive in the UK without prior permission or by irregular means. The need to campaign against unjust and racist immigration laws continues. This is why PHM is standing Together with Refugees and against the Nationality and Borders Bill.

[1] Ministers saw law’s ‘racism’ as defensible, The Guardian, 1 January 2002 https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2002/jan/01/uk.race

[2] Immigration Act 1971 at legislation.gov.uk delivered by The National Archives https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1971/77

Visit Migration: a human story until Sunday 24 April 2022. Part of a huge programme of events and exhibitions which includes PHM’s 2020-21 Banner Exhibition where you will find the Campaign Against the Immigration Laws (CAIL) banner. With support from Art Fund and The Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust.

Book a tour of Migration: a human story with PHM’s Community Programme Team on Friday 10 December 2021 at 11.00am.

Find out how you can stand with PHM and Together With Refugees and against the Nationality and Borders Bill.

Find out more about the campaign to end immigration detention from Refugee Tales who work in collaboration with migrants and people who have experienced the UK asylum system.

Read about how immigration policy has divided families with the case of Anwar Ditta and her children from Our Migration Story.

Shop Border Nation: A story of migration. All purchases support the museum, helping us continue to champion ideas worth fighting for.