Jayaben Desai was born in India in 1933 and when she married she migrated to Tanzania to join her husband. In east Africa there were rising attacks on Asians, with President of Uganda Idi Amin’s expulsion order forcing thousands of Asians to leave the country. Desai and her family were some of the Asians who migrated to Britain; they held British passports and chose to live in the colonial ‘motherland’ of Britain, moving there in 1967. This was the year before Conservative MP Enoch Powell’s ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech and a tightening of immigration controls. By the early 1970s the National Front, a fascist organisation, was on the rise, and there were a number of violent racist attacks in Britain. Jayaben took up low paid work in Britain as a sewing machinist, before moving to work at the Grunwick film processing factory in north west London. This was a time when it was very normal to send off your camera film to be developed! Working at the Grunwick factory, Desai rose to fame for her strike leadership.

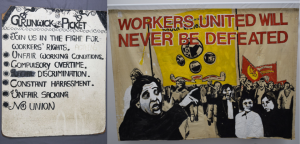

Grunwick employed many migrant workers, including a large number of Asian women stereotypically viewed by employers as submissive and hard working. The Grunwick workers recalled an atmosphere of fear and control at the factory, with the workers treated in patronising and humiliating ways. One striker described: ‘The managers were in a glass cabinet. They could see us, and if they called us into their office, the rest of the workers could see them, but could not hear what was going on. We used to work out of fear.’ Desai described: ‘They had made the rule that you had to get permission from the managers to go to the toilet. This woman said to me that she felt ashamed to ask. I said when he has no shame making you ask loudly, why should you feel ashamed?’

It was a strike at the Grunwick factory started after managers sacked a young man, and three colleagues walked out in solidarity with him. Soon after, on Friday 20 August 1976, Jayaben Desai was confronted with a short notice demand for overtime. She powerfully responded to her manager:

‘What you are running here is not a factory, it is a zoo. There are many types of animals in a zoo. Some are monkeys who dance to your tune, others are lions who can bite your head off. We are those lions, Mr Manager.’

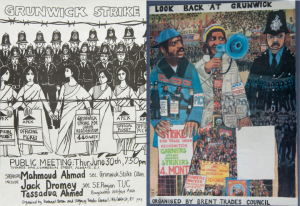

Desai and almost 100 other workers walked out in protest against their treatment – they were to strike for two years. This was a spontaneous walkout and did not initially have union backing. There had been a number of previous strikes involving black and Asian workers in Britain, particularly in the 1960s and early 1970s, which had not received trade union support. In contrast, the Grunwick strikers soon received support from the Brent Trades Council. They were encouraged to form a union and received strike pay – the strike therefore became not just about working conditions but also about trade union recognition. Grunwick saw some of the greatest scenes of black and white working class solidarity in the history of the trade union movement. As Desai argued during the strike, ‘We will not back down now. We want to bring this factory to a standstill. Our fight is for all our rights, and for our dignity. We hope all trade unionists will stand by us.’ Many workers responded to the solidarity call at Grunwick, travelling from all across Britain. President of the Yorkshire area of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) Arthur Scargill led a huge delegation from the coalfields, to join a group of overwhelmingly Asian women outside the Grunwick factory gates. Local postal workers for a period refused to touch the mail going into the Grunwick factory, in solidarity with the Grunwick strikers. There were pickets of up to 20,000 people.

The strike eventually failed. Yet the determination and solidarity during the dispute transformed the politics of race in the labour movement; Asian workers were by no means submissive and weak but were a vital part of the English working class. It was a critical moment in the interweaving of anti-racism within the trade union movement.

Find out more about Jayaben Desai and the Grunwick strike in this 2019 video from BBC World Service’s Witness History.

Dr Shirin Hirsch is a historian based jointly at People’s History Museum and Manchester Metropolitan University.

Find out if you share any similarities with Jayaben Desai by taking our Which Radical are You? quiz. At the end you will be given the option to sign up for our free e-newsletter.

Visit the museum to try out an Augmented Reality experience of the Grunwick strike.

Find out why PHM Vice-Chair of Trustees Lord Steve Bassam chose to sponsor PHM Radical Jayaben Desai in his very personal blog post.

Teach about workers’ rights with our learning resource and book a self guided visit for your learning group to explore further.