2024 marks two significant anniversaries of miners’ strikes in Britain. The 1974 Miners’ Strike and the strike of 1984 to 1985, that is etched in the memories of many.

In this third of a series of three blogs exploring these miners’ strikes, Dr Bob Dinn, Visitor Experience Supervisor at PHM, writes about the events of the 1984 to 1985 Miners’ Strike.

On 1 March 1984 the National Coal Board (NCB) unexpectedly announced the closure of Cortonwood Colliery in South Yorkshire, to take place at the beginning of April that year. Less than a week later the Cortonwood miners walked out on strike, initiating one of the most significant industrial disputes of the 20th century. The strike rapidly spread through the coal fields, polarised the country, and left a legacy in the former mining communities.

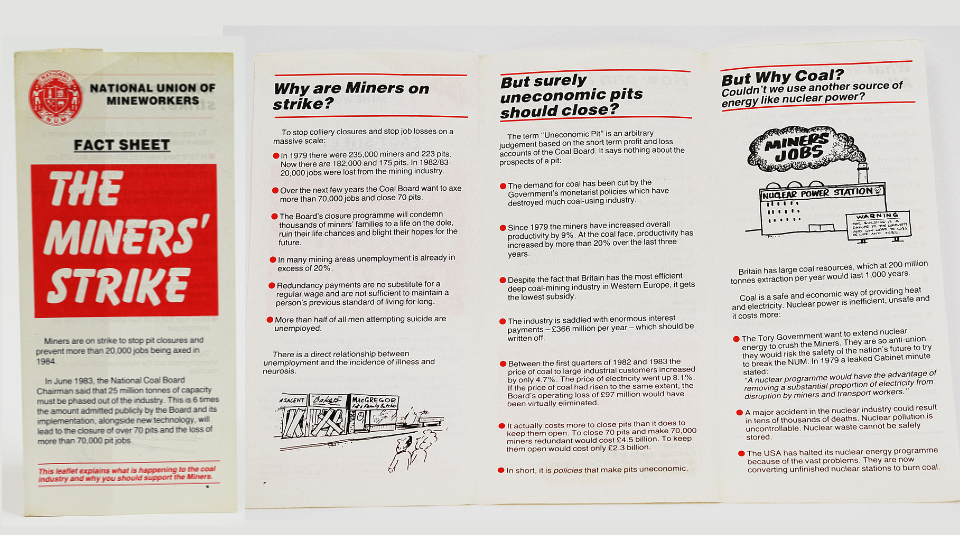

The Miners’ Strike of 1974 had brought down Prime Minister Edward Heath’s Conservative government, leading to a new Labour administration under Harold Wilson. The 1977 Ridley Plan had outlined how a future Conservative government could confront the trade unions. This included targeting specific unions, stockpiling coal in power stations, undermining union finances, and special police training to deal with picketing. Margaret Thatcher, elected in 1979, was determined to limit the trade unions which she saw as having too much political power. Coupled with her drive to privatise large nationalised industries in the name of economic efficiency, the mineworkers were an obvious target. The more immediate cause was the announcement of an accelerated pit closure programme by the National Coal Board (NCB) in late 1983. By March 1984 the NCB announced that 20 pits would close with the loss of 20,000 jobs (1), although Arthur Scargill, the leader of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), correctly argued that the plan was to close 75 pits. From that point it was clear that a confrontation between the miners and the government was likely.

In 1983 there were over 170 pits in the country, employing 187,000, with the largest concentration of pits and miners in Yorkshire, Nottinghamshire, and South Wales. Although there is some dispute about total figures, at its peak at least 142,000 miners were on strike. Support for the strike was particularly strong in Yorkshire, Scotland, Kent, and South Wales, weakest in Leicestershire, Nottinghamshire, South Derbyshire, and West Midlands.

The National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) was led by Arthur Scargill, his deputy Peter Heathfield, and regional leaders Mick McGahey (Scotland) and Emlyn Williams (Wales). Scargill was the most public figure in the strike. The National Coal Board (NCB) chair was Ian MacGregor, a Scottish-American businessman with a reputation for attacking trade unions in the US. As chair of British Steel, MacGregor had ruthlessly closed plants and halved its workforce.

One of the most contentious issues of the Miners’ Strike was the decision not to hold a national ballot. Within a fortnight of the Cortonwood walkout, only 11 pits were working normally. Local and regional ballots led to what was in effect a series of local strikes in different coalfields, rather than a national strike. NUM leader Arthur Scargill had lost three previous national strike ballots and was reluctant to put the membership’s opinion to the test again, even though his supporters believed a national ballot would have succeeded. In April 1984 a National Delegate Conference of the NUM voted 69-54 against holding a national ballot. This left the decision in the hands of the different NUM regions and individual pits, and some coalfields, including Nottinghamshire, never voted to strike. Although the NUM leadership argued powerfully that a national ballot was not required constitutionally (2), the tactic damaged their support from some trade unions and the Labour Party and was criticised in the media. It also allowed the Thatcher government to attack the NUM leadership as it broke the law that made a strike ballot mandatory.

Flying pickets were groups of striking miners, many from Yorkshire, who travelled from their coalfields to areas where the strike was weakest. This was partly to support minority striking miners, such as in Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire, and partly to try to close the mines to working miners. The use of flying pickets by the NUM was controversial and led to some of the biggest confrontations with the police, who would also stop and turn back miners on the motorways.

The strike saw high levels of violence, notably at Orgreave, Ollerton, Maltby, and Easington. The Ridley Plan, calling for the establishment of mobile police squads, trained in riot control, had set the template for policing. Police were drafted in from all over the country, often from areas with no tradition of mining and no understanding of the community, making confrontations more volatile. The tactics of riot control led to many casualties on both sides, and it was common for officers to hide their police numbers to avoid identification. Local officers, rooted in the villages, usually took a more sensitive approach to policing the picket lines. A widespread slogan during the strike was ‘close a pit, kill a community’, so it is unsurprising that some of the protests turned violent – striking miners believed they were fighting for both their economic and social survival. Nearly 10,000 miners (2) were arrested during the strike, with over 4,000 being convicted in the courts.

At Orgreave coking plant in South Yorkshire on 18 June 1984 approximately 5,000 pickets faced 6,000 police. In the violence that followed, sometimes referred to as ‘The Battle of Orgreave’, over 100 miners were injured and 95 were arrested and charged with riot or violent disorder. In 1991 39 of the convicted miners were compensated £425,000 by South Yorkshire Police, for assault by the police, wrongful arrest, and wrongful prosecution.

On 3 March 1985, following a narrow majority decision by the NUM executive, the miners returned to work, at many pits processing with banners and bands. As the strike progressed the hardship experienced by the miners intensified. The NUM’s assets had been frozen in October 1984 and miners were becoming increasingly dependent on voluntary contributions. A $1 million donation from Soviet miners, authorised by future Soviet Union leader Mikhail Gorbachev, was eventually blocked so that the USSR could cultivate relations with western governments. The Thatcher government’s policy of stockpiling coal meant that the power stations had remained open during the 1984 to 1985 winter, and by early 1985 increasing numbers of miners were drifting back to work; remaining on strike was no longer an option.

Within a very short period the pit closure programme was fully implemented. By 1994 only 15 of the 174 pits remained open, and there are now only two mines remaining in the UK. Scargill’s predictions had proved largely correct. Pit villages became blighted with mass unemployment and social deprivation, and many of the strikers never worked again. However, others retrained, some becoming actively involved in politics as local councillors and MPs, and one of the positive effects of the strike was the empowerment of women. The culture of the pit communities continues to live through the brass band tradition and annual events like the Durham Miners’ Gala.

Explore PHM’s Miners’ Strike collections on an archive exploration and guided gallery tour.

View the Miners’ Strike 1984 to 1985 archive guide and discover material about the strike in the museum’s archive.

Visit the galleries at People’s History Museum, where you can view objects, photographs, and participants’ testimonies from the 1984 to 1985 Miners’ Strike.

Don’t miss the Collection Spotlight in Gallery One, display of objects highlighting the role of women in the 1984 to 1985 Miners’ Strike.

Read also in this series a blog from PHM Researcher Dr Shirin Hirsch, taking us back to the earlier and lesser known strikes including the 1974 Miners’ Strike and the legacy this created for the years that followed. We also hear from Amy Todd, a PhD student working for PHM, whose blog explores the women’s movement against pit closures during the 1984 to 1985 Miners’ Strike.