The great granddaughter of Sarah Chapman, one of the leaders of the 1888 Match Girls' Strike, details the strike and uncovers a very personal story.

Sam Johnson, great granddaughter of Sarah Chapman, one of the leaders of the 1888 Match Girls’ Strike, details the strike and uncovers Sarah’s personal story and Sam’s mission for her unmarked grave.

At the Bryant & May match factory in Bow, east London, many workers were very young girls and women, working long hours for little pay, with fines for petty offences. They also had to work with dangerous white phosphorus that could cause a form of cancer known as ‘phossy jaw’. Unrest was mounting and then came an unexpected external spark. On 15 June 1888, at a Fabian Society meeting, Henry Hyde Champion reported 20% dividends at the factory while workers got ‘starvation wages’. He proposed a boycott on Bryant & May matches, which was passed unanimously.

Annie Besant (1847-1933), a prominent social reformer and Fabian, met with some workers outside the factory to find out more about their conditions, which led to her article, White Slavery in London in the newspaper The Link (23 June 1888). Bryant & May were furious and tried to cover up the allegations by forcing their workers to sign false statements. They refused.

The final straw was a dismissal of one of the girls at the factory – 1,400 girls and women walked out on strike, on 5 July 1888. They wrote to Annie:

‘My Dear Lady, – we thank you very much for the kind interest you have taken in us poor girls, and hope that you will succeed in your undertakings. Dear lady, you need not trouble yourself about the letter I read in the Link that Mr. Bryant sent you, because you have spoken the truth, and we are very pleased to read it. Dear lady, they are trying to get the poor girls to say that it is all lies that has been printed, and trying to make them sign papers to say it is lies; dear lady, no one knows what we have to put up with, and we will not sign them. We all thank you very much for the kindness you have shown to us. My dear lady, we hope you will not get into any trouble in our behalf, as what you have spoken is quite true; dear lady, we hope that if there will be any meeting we hope you will let us know it in the book. I have no more to say at present, from yours truly, with kind friends wishes for you, dear lady, for the kind love you have shown us poor girls. Dear lady do not mention the date this letter was written or I might have put my or our names, but we are frightened, do keep that as a secret, we know you will do that dear lady.’

The next day 200 workers marched to Annie’s office in Bouverie Street, London, where The Link was published

‘You had spoke up for us and we weren’t going back on you’

Annie Besant spoke to three of them and, despite not favouring strike action, agreed to help. Plans were made for a strike committee.

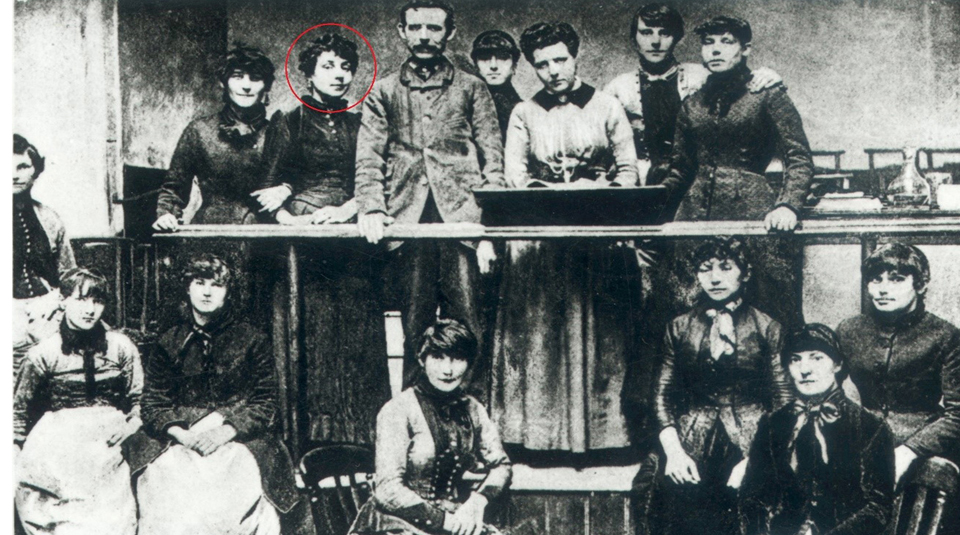

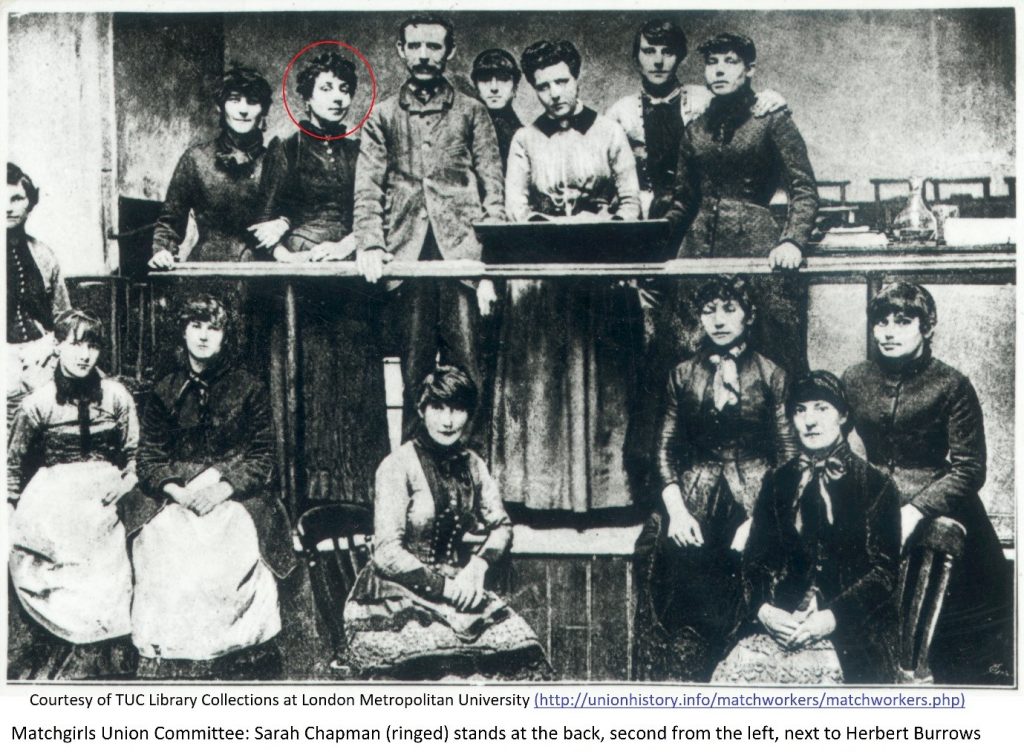

The first members of the committee were Sarah Chapman, Mrs Mary Cummings, Mary Driscoll, Alice Francis, Eliza Martin, Mrs Mary Naulls, Kate Sclater and Jane Wakeling.

The strikers held their first meeting on Mile End Waste, a large open space frequently used for such gatherings.. Some newspapers provided positive publicity and MPs started to listen, which led to Annie Besant taking a deputation of match girls to parliament to meet two MPs. On a wave of optimism and courage, in just under a fortnight, the Match Girls’ Strike Committee, supported by the London Trades Council, met with Bryant & May. All the strike demands were met – a momentous victory for workers’ and women’s rights. The news was greeted by ‘wild cheering’.

The inaugural meeting of the Union of Women Matchmakers took place at Stepney Meeting Hall and 12 women were officially elected to the committee:

Louisa Beck, Sarah Chapman, Mary Driscoll, Alice Francis, Julia Gamelton, Ellen Johnson, Eliza Martin, Mrs Mary Naulls, Eliza Price, Kate Sclater, Jane Staines and Jane Wakeling.

Sarah Dearman (née Chapman) was my Great Grandmother. It was only in 2016 that I discovered how brave and historically important she was, thanks to Dr Anna Robinson’s MA thesis, ‘Neither Hidden Nor Condescended To: Overlooking Sarah Chapman‘.

Sarah was born in 1862 in Mile End, east London and at least by the time she was 19, was a matchmaking machinist. So why do I assert her as one of the strike leaders?

She was one of the delegation of three who met with Annie Besant after the match girls marched to her office on Bouverie Street, and she was on the strike committee, so she was almost certainly in the delegation that met MPs and would have discussed terms with Bryant & May at the end of the strike.

Significantly, Sarah was elected to the new Union Committee and was their first representative to the International Trades Union Congress (TUC) in November 1888; a sign that she was highly regarded by others. She attended with Annie Besant and was one of only 77 delegates. As one of only 10 women out of almost 500 delegates, she also attended the 1890 TUC conference in Liverpool and seconded a motion related to The Truck Act.

In 1891 Sarah left the factory and married Charles Dearman. They had six children, three of whom predeceased Sarah. She lived to see women get the vote, and survived the Blitz, but ended up in a pauper’s grave in Manor Park Cemetery & Crematorium, east London at the end of 1945.

Thanks to Anna Robinson, I found Sarah’s unmarked grave in 2017. Devastatingly, it is threatened with ‘mounding’ – a brutal process where mechanical diggers flatten the ground, new soil is added and new burials made; risking disturbing existing remains. We have funds for a headstone (thanks to donations from Unite the Union and GMB union) and an active campaign to stop the mounding so we can erect her headstone.

To recognise the match girls’ contribution to the advancing of human rights, equality and workers’ rights, we have a charity, The Matchgirls Memorial, dedicated to keeping their legacy alive, via a statue and other memorials, including murals, mosaics, street naming, plays, heritage trails, art, poetry and music, in the community and schools. It is vital people are aware of their heritage, especially since many of the issues sadly still resonate today.

Sam Johnson is the great granddaughter of Sarah Chapman, one of the leaders of the 1888 Match Girls’ Strike.

Guest blogs are not curated by PHM but feature voices on topics relevant to the museum’s collection. Guest blogs do not necessarily reflect the views of PHM. Photographs supplied by contributor.

Email: matchgirls1888statue@gmail.com

Twitter: @TheMatchgirls

Facebook: @TheMatchgirlsMemorial

Instagram: @matchgirls1888statue

At People’s History Museum (PHM) in Main Gallery One, visitors can explore the harsh working conditions at the Bryant & May match factory through an arcade style game, where players’ progress is hampered by unfair fines and sickness.

This is one of two new digital experiences at PHM that have been selected by the Digital Leaders 100 Awards as one of the top 10 Cross-Sector Digital Collaborations of the year. These interactives use digital technology to enable visitors to the national museum of democracy to take part in experiences that help to bring to life the stories of the Match Girls’ Strike (1888) and the Grunwick strike (1976-1978).

A public vote will now determine which projects make it to the final DL100 list, which is published each year by the Digital Leaders Awards. Vote for People’s History Museum’s ‘History Makers’ and help us continue to raise the profile of the people who champion ideas worth fighting for.

Funded by AIM Biffa Award, developed in collaboration with the Creative AR & VR Hub at Manchester Metropolitan University to raise the profile of two important History Makers; Annie Besant and Jayaben Desai

Teach about workers’ rights with our learning resource and book a self guided visit for your learning group to explore further.

Find out if you share any similarities with Annie Besant by taking our Which Radical are You? quiz. At the end you will be given the option to sign up for our free e-newsletter.