Part of the national commemorations marking 200 years since the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester in 1819, this exhibition told the story of Peterloo and highlighted its relevance in 2019.

The exhibition featured objects, including original Peterloo artefacts, brought together for the very first time, alongside pieces telling more recent stories of protest. A short film commissioned especially for the exhibition brought to life the story of Peterloo, protest, and the road to democratic reform.

A creative space within the exhibition was Protest Lab; an experimental gallery for individuals, communities and organisations to use to share and develop their views and ideas for collective action. Protest Lab examined the issues that people were campaigning for 200 after Peterloo.

The exhibition was central to PHM’s year long programme exploring the past, present and future of protest.

A short film commissioned especially for the exhibition brought to life the story of Peterloo, protest and the road to democratic reform.

Men, women and children walked from towns and villages in and around Greater Manchester. Some walking nearly 30 miles. Many had come especially to see the famous Henry Hunt speak on the need for electoral reform.

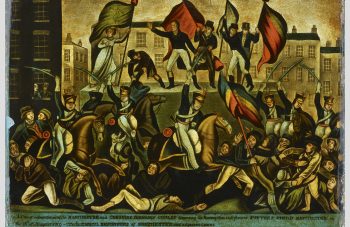

This rare glass painting shows the Manchester authorities violently dispersing the crowd. Although different sources give different estimates of the numbers attending the meeting and the numbers killed and injured, it seems likely that 60,000 people attended the meeting, 18 people were killed and around 700 were injured.

This painting is of the central part of a famous print The Peterloo Massacre published by radical printer Richard Carlile in 1819. Our research suggests it was probably done by a local artist a few years after the massacre. This type of glass painting was a popular art form in the early 19th century, often displayed in pubs and homes.

Peterloo commemorative glass

Oil paint on glass in a wooden frame

Date unknown

Purchased by People’s History Museum with assistance from The National Lottery Heritage Fund Collecting Cultures programme.

In 1819 around 2% of the British population had the right to vote and Manchester did not have its own Member of Parliament (MP). Wages had halved since the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and rising food prices left many unable to afford basic foods like bread. The people wanted a voice and the demand for representation in parliament was growing.

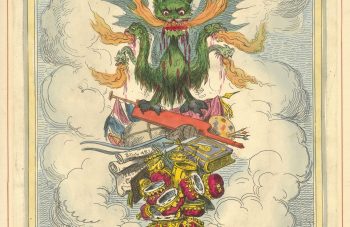

This engraving was printed one month before the Peterloo Massacre. It was designed to warn of the dangers of giving more people the vote and potential revolution.

The monster in the print represents radical reform; it stands victorious over the cherished British institutions of the arts, royalty and religion.

Hostility and fear was growing amongst those loyal to the government and opposed to reform. On 21 July 1819 the Manchester’s magistrates announced the formation of a Loyal Association to combat ‘the attempts of seditious men to overturn the Constitution and to involve us in the miseries of a Revolution’.

Universal Suffrage or the Scum Uppermost

Hand coloured engraving on paper

George Cruikshank, July 1819

Purchased by People’s History Museum with assistance from The National Lottery Heritage Fund Collecting Cultures programme.

The yeomanry explicitly targeted women during the gruesome dispersal. More than 25% of all casualties were female, even though they comprised only 12% of those present. Women active in the reform movement of the time dressed distinctively in white cotton as a symbol of their virtue.

Mary Fildes, President of the Manchester Female Reform Society, was herself truncheoned by special constables when she refused to let go of the flag she was carrying.

A Mrs Mabbott wore this dress on 16 August 1819. She was a confectionary shop owner from Shude Hill. Rather than being an active participant in the protest, our research suggests that Mrs Mabbott was caught up in the violence of the day.

A silk dress with bodice was expensive and not likely to have been worn by any of the many female reformers present. However, it does show how much the chaos of day spread through the city centre.

Mrs Mabbott’s dress

Fawn corded silk with a white linen lined bodice and sleeves

Around 1819

On loan from Manchester Art Gallery, a gift from Miss A Sherlock, 1948.

The magistrates read the Riot Act but nobody heard. The crowd panicked when the yeomanry rode in on horses armed with sabres. They slashed and hacked at men, women and children in an attempt to arrest Henry Hunt and break up the meeting.

The Manchester and Salford Yeomanry were a force of volunteer soldiers working for local government leaders. They were made up mostly of local businessmen and were hostile to the reformers. Hugh Hornby Birley, Manchester mill owner and captain of the yeomanry, ordered the soldiers into the crowd.

More than 300 harrowing eyewitness accounts provide a powerful testimony of the brutality of events on the day. Within these accounts Hugh Hornby Birley’s cruelty and violence was often noted. This portrait shows off his wealth and power. We do not have similar portraits for the ordinary protestors at Peterloo.

Portrait of Hugh Hornby Birley, captain of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry

Oil paint on canvas

Date unknown

Gift from Dr Rick Birley, 2018 with assistance from The National Lottery Heritage Fund Collecting Cultures programme.

Many braved the oppressive Six Acts, to express their anger in print. The radical press played an important role in keeping the reform movement going. The Manchester Guardian newspaper (now known as The Guardian national newspaper) began in 1821 as a direct consequence of what happened at St Peter’s Field. The attempt to silence government critics only encouraged journalists to develop inventive new ways of conveying the message of reform.

William Hone was an English radical writer and publisher active in the early 19th century. In partnership with illustrator George Cruikshank, Hone published a number of political works, most of which aimed to highlight the abuses of political office.

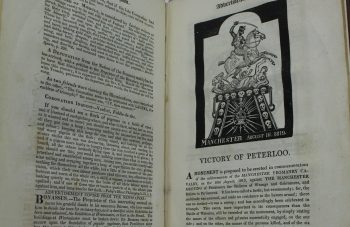

Hone and Cruikshank’s A Slap at Slop was first published in 1821 as a short satirical news sheet. Most notably, it covers the Peterloo Massacre, featuring a satirical design for both a monument and medal for the soldiers of Peterloo.

A Slap at Slop and The Bridge Street Gang

Card bound with paper text block

William Hone and George Cruikshank, 1821

On loan from the Working Class Movement Library, purchased with assistance from The National Lottery Heritage Fund Collecting Cultures programme.

Despite widespread public sympathy in response to the massacre, the government’s immediate response was to toughen laws, which limited the freedoms of both the public and the press. The new legislation became known as the Six Acts.

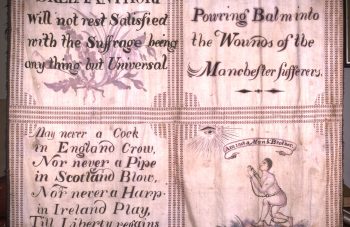

Even with these new oppressive laws, people continued to meet in secret in support of reform. This flag is one of the most impressive survivors from these times. It had to be hidden between meetings and buried in a specially made box. Anyone found in possession of it would have been arrested.

It is believed to have been made in 1819 by a Mrs Bird, a pattern maker from Radcliffe Street in Skelmanthorpe, a village near Huddersfield, to honour the victims of the Peterloo Massacre.

The bound man is a depiction of a slave in chains. The use of this symbol reflects the influence of the abolition movement on the new struggles for democracy in Britain.

The Skelmanthorpe flag

Oil paint on cotton with decorative wool edging

Around 1819

On loan from Tolson Museum, Huddersfield.

The Peterloo Massacre was a key milestone on the road to democratic reform. The massacre was a catalyst for subsequent generations campaigning for change.

This ballot box is a testament to one of the many milestones that came after Peterloo. The 1872 Secret Ballot Act allowed voters to elect a Member of Parliament (MP) in secret by placing an ‘X’ on a ballot paper next to the name of their choice, rather than voicing their vote in public beneath the gaze of employers or landlords.

This ballot box was used in the first ever election held after the passing of the act, during a by-election in Pontefract, West Yorkshire in August 1872. The box is still marked with the seals used to ensure the votes were not tampered with. The seal was made with a liquorice stamp, the same liquorice used to make Pontefract cakes in a local sweet factory.

Further milestones of reform can be discovered in the main galleries.

Pontefract secret ballot box

Painted wood and iron alloy

August 1872

On loan from Wakefield Council.

As well as political prints and poems, everyday items such as ceramic jugs and handkerchiefs immortalised and commemorated Peterloo. Such items showed the owner’s support of the reform cause, and helped sustain the memories of its martyrs.

There were a number of commemorative medals produced following the massacre, however, this medal is believed to be one of the only surviving examples of its kind.

It features a much more hostile and angry slogan than medals produced later;

an example of which can be found in Main Gallery One.

It is thought that the medal may have been produced to raise funds for the victims of the massacre, although this is unconfirmed.

Peterloo commemorative medal

Iron alloy

Around 1819

Purchased by People’s History Museum with assistance from The National Lottery Heritage Fund Collecting Cultures programme.

The exhibition also told more recent stories of protest through Protest Lab a creative space within the headline exhibition: an experimental gallery for individuals, communities and organisations to use to share and develop their views and ideas for collective action. Visitors were invited to answer the question How Have You Protested? by lending their own objects that told a story of protest. Over the course of the exhibition, hundreds of objects were added to the exhibition.

Find out more

An interactive timeline invited visitors to add significant protests between 1819 and 2019 using postcards. 1356 postcards were added to the timeline documenting protests from around the world including those that took place during the course of the exhibition including Brexit marches, Extinction Rebellion protests and the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. This Prezi presentation created by volunteer Katie Bower takes a closer look at just some of the protests that were documented on the timeline.

Explore the timeline

During the exhibition young people from RECLAIM, 42nd Street and a Manchester Pupil Referral Unit worked with artist Andrew Westle to explore what protest meant to them and the issues that they wanted to amplify.

Find out more

‘So important to remember how hard our ancestors fought for all democratic rights. We must defend them. We must defend our right to protest, our right to differing opinions. And we must continue to work for more equality, more tolerance, more justice, more LOVE. France, 08/19’

‘Thank you for this exhibition. It let me know democracy is precious. Freedom is not free. I will go back to Hong Kong a few days later…After I visit the exhibition, I know. We may not make progress in our fights. But it will be one of our war in democracy. 15/9/2019’

‘This is a unique exhibition that represents something vital to us all – the right to protest and its power to garner change – a wonderful message. Patrick, Ireland’

‘So important to remember Peterloo and link the past to the present. This exhibition feels very relevant to today. Made me feel quite emotional and proud to be a Manc!’