In February 2020, to mark ten years in the museum’s current home, PHM's team picked out ten pieces that they believe capture the ethos, spirit and importance of the museum’s collection.

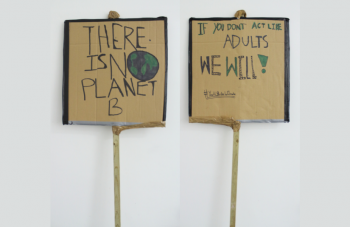

In 2019 PHM spent the year exploring the theme of protest. Audiences particularly responded on the issue of environmental protest, reflecting what was happening and concerning them in the wider world. The placard ‘There Is No Planet B’ was collected at the first Youth Climate Strike in Manchester, which was held in February 2019. As a museum that tells the story of ideas worth fighting for, contemporary collecting is vital – which is powerfully summed up by this piece.

Michael Powell, Programme Officer at People’s History Museum, says ‘What campaigners have done to place the environmental crisis on the political and media agenda and the progress they’ve achieved in a relatively short space of time is incredible. The creative non-violent direct action of Extinction Rebellion and Greta Thunberg and the Youth Climate Strikes campaign has achieved a ground swell of people involved in different ways. Their story powerfully symbolises the ideas worth fighting for of today, which we’ll be talking about for years to come at People’s History Museum.’

Where can you see this item or find out more?

Not currently on public display. Contact collections@phm.org.uk to arrange to view the object.

On 27 October 2019 there was a ‘There is no planet B’ creative disobedience day, at the museum which put the environment in the spotlight. Read ten year old youth activist Lillia’s guest blog about what’s at stake and how she is standing up for climate justice.

Did you know?

In 2019 PHM and many other organisations, including Tate and Nottingham Contemporary, declared a climate and ecological emergency.

Contemporary collecting is very important to PHM, so we were delighted when actor Julie Hesmondhalgh donated the iconic coat that she wore in ITV’s Coronation Street from 1998 to 2014 while playing the UK’s first transgender soap character. The storyline was influential in helping to shift opinions, but also brought criticism for the failure to cast a trans person to play the role. Throughout and since Julie has been a huge advocate for the transgender community.

The coat came to PHM as part of the work that was done to collect for the 2017 exhibition Never Going Underground: The Fight for LGBT+ Rights; during a year in which the museum marked the 50th anniversary of the partial decriminalisation of homosexual acts in England and Wales (1967 Sexual Offences Act).

Liz Thorpe, Learning Officer at People’s History Museum, says ‘2017 was a year to be proud of. It really felt like a coming together of different communities to tell an important story through the objects that shaped their lives. Having never before handed over so much curatorial control there were a lot of uncertainties on what the outcome would look like, but the end result felt much more than a successful exhibition or event launch. It felt like a coming together of people that was full of interesting conversations and emotions.’

Where can you see this item or find out more?

Not currently on public display. Contact collections@phm.org.uk to arrange to view the object.

Previously loaned to the National Science and Media Museum for their exhibition Switched On (23 July 2022 – 11 January 2023), a journey through a century of broadcasting innovations.

Previously on display in PHM’s exhibition Never Going Underground: The Fight for LGBT+ Rights (25 February – 3 September 2017).

Find out more about the museum’s LGBT+ collection.

Did you know?

‘Never Going Underground’ was the name of the North West Campaign for Lesbian and Gay Equality’s movement against Section 28 of the 1988 Local Government Act that banned schools and local authorities from the ‘promotion of homosexuality…as a pretended family relationship’. Subversively adopting the symbol for the London Underground as its logo, the campaign included the UK’s largest ever gathering for LGBT+ rights in Manchester the same year.

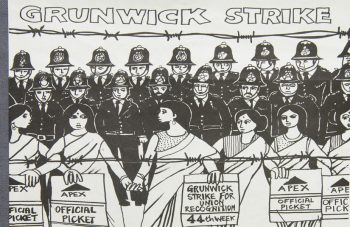

The Grunwick strike (1976-1978) is an important moment in the storytelling of the national museum of democracy, not only because of the action taken by workers, but because it marks a particularly significant chapter of history concerning race relations. The museum holds a number of pieces about the strike, but this poster stands out as a real treasure because of its beautifully hand drawn illustration used to publicise a public meeting held by Bethnal Green and Stepney Trades Council in London.

Workers at the Grunwick film processing factory in London were seeking trade union recognition. The strike was led by Jayaben Desai, who, like many of the protesting workers, was a newly arrived immigrant.

Zofia Kufeldt, Programme Officer at People’s History Museum, says ‘The Grunwick strike, although not successful, was a unique moment that will be remembered for the way thousands of people came together to defend the rights of migrant workers. It sent a message about migrant workers’ place in society and collectively confronting racism at work, both of which are themes explored throughout the 2020 programme on migration.’

Where can you see this item or find out more?

Not currently on public display. Contact collections@phm.org.uk to arrange to view the object.

Find out more about PHM’s programme for 2020 to 2021 exploring migration, co-created by a Community Programme Team made up of people whose lives have been shaped by migration.

Read Zofia Kufeldt, PHM Programme Officer’s blog putting the spotlight on this treasure in PHM’s collection, as she goes back to Grunwick to explore it’s relevance today.

Did you know?

The events of the Grunwick strike are illuminated in an augmented reality (AR) experience in Gallery Two at PHM.

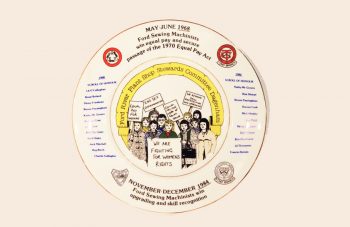

Like so much of PHM’s collection, there is great symbolism to this piece. It was created to commemorate the Dagenham Ford sewing machinists’ gaining of equal pay following their strike in 1968, but also reflects a story of considerable contemporary relevance. It was in 1970 that the Equal Pay Act was passed following the strike, in which women workers were demanding to be paid the same as men doing equivalent jobs. Whilst the quest for equal pay would lead to the 1970 act, the recognition of their work being skilled, which was seen as just as important, took another 16 years to resolve. Both chapters of history are recognised on the plate.

Alice Parsons, Engagement Manager at People’s History Museum, says ‘This plate is an important reminder that the fight for equality is an ongoing process and that every step forward should be acknowledged and celebrated. The gender pay gap still exists in 2020 but people continue to raise awareness of it and challenge it, just as the Dagenham Ford sewing machinists did. I hope that soon we might be commemorating the elimination of the gap.’

Where can you see this item or find out more?

On display in Gallery Two.

Did you know?

Barbara Castle, who was the Secretary of State for Employment (1968-1970) met with the striking women at Ford’s Dagenham plant to help negotiate a settlement that would lead to the Equal Pay Act (1970).

Cliff Rowe (1904-1989) was an artist that used his paintbrush to draw attention to the ideas he believed in. He spent much of his professional life visiting factories and painting the workers that he saw, it is these images that dominate the vast collection that was donated by the artist to PHM in 1985. The painting here of a female scientist at work reflects a common theme for Rowe; one that is fascinating to reflect upon from a contemporary perspective.

Rowe lived and worked in Russia in the early 1930s, at a time when back home Britain was going through the Great Depression. His experiences would see him go on to create the Artists’ International Association in 1933, the aim of which was to use art as an influential tool in the class struggle and to promote peace. Rowe’s own story is as intriguing as the work that he produced.

Kloe Rumsey, Conservator at People’s History Museum, says ‘I love the style, colour use, and changes in the collection we have at PHM, but I particularly love the depictions of women in science and industry. The professional and unromantic insight into women’s everyday lives of the time is rare and very valuable to today’s audiences. They are often painted on MDF wood which deteriorates badly, so we have been cataloguing, recording, and storing them safely; and there is much more to discover in the rest of the collection.’

Where can you see this item or find out more?

Not currently on public display. Contact collections@phm.org.uk to arrange to view the object.

In July 2020, members of PHM’s staff team looked at the museum’s Cliff Rowe collection in the context of Covid-19 and picked paintings that resonated with them. Explore these staff picks on Art UK’s website, the online home for every public art collection in the UK.

Read Liz Thorpe, PHM Learning Officer’s blog putting the spotlight on this treasure in PHM’s collection, and sharing activities to improve our wellbeing inspired by PHM’s wider collection of Cliff Rowe paintings.

Did you know?

Cliff Rowe was a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, the complete holdings of which are held in the museum’s archive for researchers to view.

It was following a crowdfunder that the Manchester suffragette banner came into PHM’s collection in 2017. Having appeared alongside Emmeline Pankhurst during some of her most significant speeches, including when she addressed a crowd of 50,000 people at Heaton Park in Manchester (19 July 1908), the banner had been out of the public eye for almost a century. The timing of its discovery couldn’t have been more symbolic, and meant that in 2018 the Manchester suffragette banner was able to play a starring role in marking the centenary of the first women achieving the vote and represent all of those who had fought for the right to do so.

Jenny Mabbott, Head of Collections & Engagement at People’s History Museum, says ‘The significance of this banner to the history of women’s suffrage cannot be overstated. Created at the height of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) campaign, it is the work of renowned banner maker Thomas Brown & Sons. But what makes it really special is the fact that it stood on the same platform as Emmeline Pankhurst, in whose honour it is made, when she gave some of her most famous speeches.’

Where can you see this item or find out more?

Not currently on public display. Contact collections@phm.org.uk to arrange to view the object.

You can see the banner in a virtual tour of the exhibition Represent? Voices 100 Years On (2 June 2018 – 3 February 2019).

Discover more in Head of Collections & Engagement Jenny Mabbott’s blog post exploring this treasure in PHM’s collection, which appeared in the final episode of the Channel 4 series Britain’s Most Historic Towns with Professor Alice Roberts on 19 December 2020.

Did you know?

The Manchester suffragette banner inspired the title of a book First in the Fight: 20 Women Who Made Manchester, published in 2019 telling the stories of 20 radical Manchester women including Emmeline Pankhurst. The book is available to buy from PHM’s shop, where all purchases made support the museum.

PHM has the world’s largest collection of trade union and political banners, making the oldest trade union banner a prize piece. It was made by William Dixon for the celebration of the coronation of George IV (19 July 1821). On permanent display it takes its place alongside both contemporary and historical banners which are changed every January to enable the public to see as much of the vast collection as possible. The oil on linen piece is fragile, but with a specialist in-house Conservation Team, PHM really is the best place for it to be.

Jenny van Enckevort, Conservation Manager at People’s History Museum, says ‘This is an example of an early trade union banner that is derived from a flag like configuration, both in terms of its proportions and the addition of the Union Flag in the upper corner. There is also evidence that it was once flown from the right hand vertical edge but was later altered with pole loops across the top, thus enabling the image to be seen clearly. Alterations such as these are common with social history objects. Conservators can spend hundreds of hours working on a single banner so we get to know it inside out; this close interrogation is an important part of understanding our cultural heritage and helps the stories we tell at the museum come to life.’

Where can you see this item?

On display in Gallery One.

Did you know?

Although this banner dates back to 1821, the history of trade unions actually goes back much further than you may think. The concept of a trade union, or a body of workers joining together to protect their own interests, has a long history. Find out more about trade unions of the Middle Ages in this blog post from Dr Claire Kennan, from the Department of History at Royal Holloway, University of London.

Historical objects from the working class are very rare in museums, and none more so than an item from the Peterloo Massacre (16 August 1819). The reaction of the authorities to the peaceful protest, which ended with significant deaths, injuries and imprisonments, meant that those who were present kept a very low profile in the aftermath for fear of the repercussions. So to have a cane that was carried by one of the protestors at Peterloo is immensely special for PHM, particularly as it was donated by a descendant of the owner as part of the activities to mark the 200th anniversary of Peterloo. The inscriptions tell a little of what this artefact has witnessed, with the words ‘brought to justice’ seen amongst them.

Sam Jenkins, Collections Manager at People’s History Museum, says ‘It was almost unbelievable to be given such a fantastic and rare object. This cane is a real connection to the men and women who met at St Peter’s Field in Manchester to call for reform, and were cut down for it. Such a tangible link to working class history is like gold dust, and it’s a real privilege to be able to share this story with future generations.’

Where can you see this item or find out more?

On display in Gallery One.

Previously on display in the exhibition Disrupt! Peterloo and Protest (23 March 2019 – 23 February 2020). Find out more about what happened in Manchester on 16 August 1819 from PHM Researcher Dr Shirin Hirsch.

Read Sam Jenkins. PHM Collections Officer’s blog to discover how clues from the past were pieced together to reveal the story of this treasured object carried at Peterloo.

Did you know?

Canes would have been carried as part of the ‘Sunday best’ attire of many of those marching at Peterloo; this was a day that began with people dressed up in their finest clothes, enjoying picnics, singing and dancing. It would end in the death of 18 people and the injury of around 700.

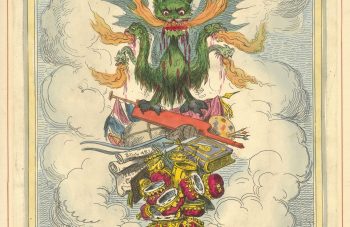

Cartoons form a significant part of the collection at PHM, both historical and contemporary. This piece was commissioned by influential London print shop owner George Humphrey in July 1819, just one month before the Peterloo Massacre of August 1819.

It was designed to warn of the dangers of radical reform and potential revolution. Humphrey’s customers were mainly wealthy upper class men, many of whom were anxious about growing demands from the working class for the vote. Cruikshank produced many similar anti-reform prints for Humphrey, but it’s difficult to say if he had any sympathy for the print’s message. His motivation may have been largely financial, as he also created many anti-establishment works during this same period.

Mark Wilson, Exhibitions Officer at People’s History Museum, says ‘For me this is one of the most interesting objects in PHM’s collection. It is a typically bold George Cruikshank creation. The print depicts a multi-headed beast perched atop a smoking mound, made up of the discarded symbols of royalty, religion and the arts. The many headed monster balances a cap of liberty on its tail; an emblem of the French Revolution. Beyond its visual invention and assured draughtsmanship, the print also offers us a window into the attitudes that would directly fuel the events of the Peterloo Massacre on 16 August 1819 in Manchester.’

Where can you see this item or find out more?

Not currently on public display. Contact collections@phm.org.uk to arrange to view the object.

Previously on display in Disrupt! Peterloo and Protest exhibition (23 March 2019 – 23 February 2020).

Read Mark’s blog putting the spotlight on this 200 year old treasure in PHM’s collection, revealing why fake news is old news.

Did you know?

Together with radical publisher William Hone, Cruikshank would produce numerous satirical pamphlets; amongst the most popular of which was The Political House that Jack Built, which was published soon after Peterloo and is an attack on the British government and lack of democratic representation.

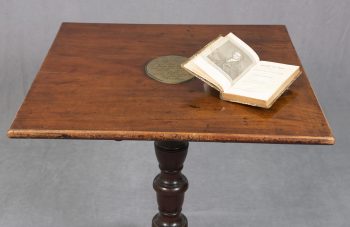

The story of writer and political activist Thomas Paine is a fascinating one; a man who shook the world with his radical writings. The second part of the most famous of these, Rights of Man (1791), was written on this desk. In the book he suggested that all men over the age of 21 should receive the vote. The British authorities were outraged at the suggestion, they banned the book and Paine fled to France.

Paine would eventually settle in the USA, where he’d spent some of his earlier life, and where his active support of the American Revolution (1765-1783) earned him a place as one of the Founding Fathers. ‘A share in two revolutions is living to some purpose’ Paine wrote excitedly to George Washington. The desk illuminates Paine’s story and reminds us that, even with the passage of time, many of his ideas remain as radical as the day they were written.

Dr Shirin Hirsch, Researcher at People’s History Museum, says ‘You can imagine Paine at his desk here hard at work on his polemical writing. At three shillings part one of Rights of Man was expensive, but at once it became a bestseller. The second part of the book was followed up the next year, on similar lines but with even stronger language. Despite a huge propaganda campaign against the book, nothing could stop its success and by the time of Paine’s death in 1809 it had sold over one million copies. Paine’s words unleashed a mass desire for change in British society.’

Where can you see this item or find out more?

On display in Gallery One.

Find out more about Thomas Paine from Salford’s Working Class Movement Library (WCML) exhibition, Thomas Paine: citizen of the world (27 November 2019 – 10 January 2021).

Which radical are you? Could it be Thomas Paine? Take our fast and fun quiz to find out, and help us match your interests to what’s on offer from PHM.

Did you know?

Paine died in the USA in 1809, but in 1819 his bones were dug up by journalist William Cobbett who brought them to England in an attempt to give them a proper burial. He arrived in Liverpool and travelled to Manchester where in November 1819, with the aftermath of the Peterloo Massacre still very fresh in the minds of the authorities, he was turned away from the city and the bones disappeared!